Places to celebrate Women’s History Month

Published 1:30 pm Wednesday, March 23, 2022

Lissandra Melo // Shutterstock

Places to celebrate Women’s History Month

In 1978, residents of Sonoma County, California, held the country’s first Women’s History Week. The goal of the event, which took place in early March to coincide with International Women’s Day, was to shine a light on the way women have impacted and contributed to the nation’s history. It was so successful that over the next several years, dozens of other towns and communities began to hold their own versions of the celebration.

In 1980, a group of women led by the National Women’s History Project lobbied the government for recognition of the week, and President Jimmy Carter became the first government official to declare March 2–8 as National Women’s History Week. A week turned to a month in 1987, and, since 1995, every U.S. president has issued an official proclamation that designates March as Women’s History Month.

In that first presidential proclamation, President Carter wrote, “From the first settlers who came to our shores, from the first American Indian families who befriended them, men and women have worked together to build this nation. Too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength, and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well.”

This year, in honor of Women’s History Month, Bounce explored a range of locations people can visit to celebrate and learn about influential women from U.S. history. Though this is just a small sampling of locations, these spots all offer different experiences and incredible insights.

![]()

EWY Media // Shutterstock

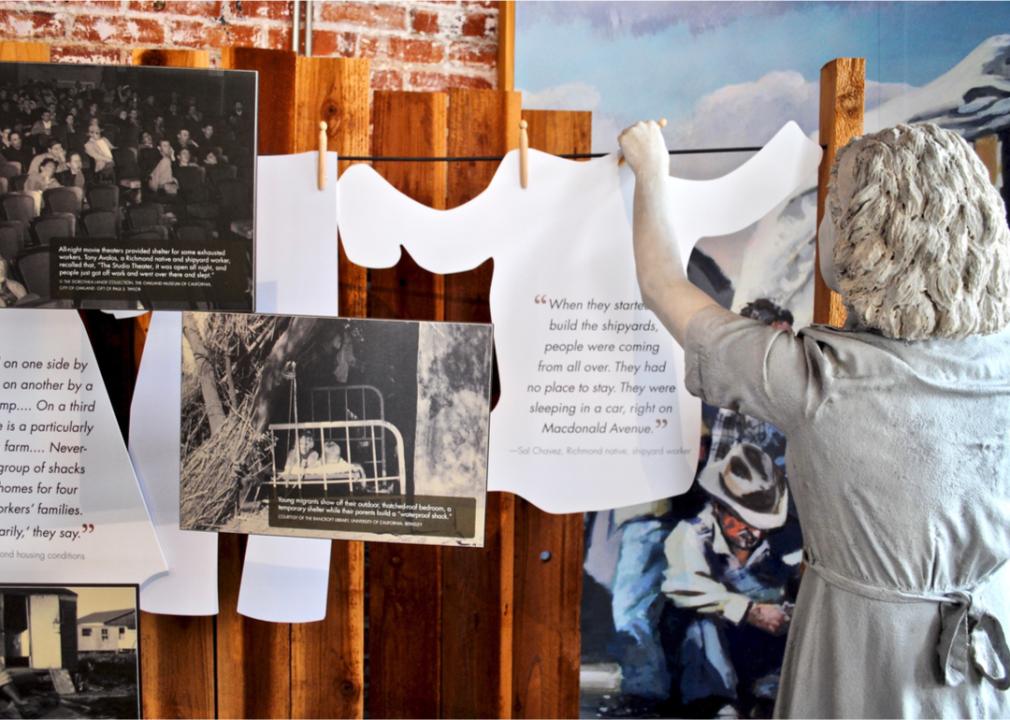

Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park

– Richmond, California

– Visiting info: The Visitor Center is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., seven days per week

During World War II, more than 10 million American men served in the armed forces. Many women were kept out of the military but found other ways to support the cause by joining the home front. Six million civilian women, inspired by a mostly fictional Rosie the Riveter and her “We can do it!” attitude, entered the workforce, doing everything from building planes to assembling munitions.

The Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California, pays tribute to the American women of WWII and the sacrifices they made—between the Pearl Harbor attack and D-Day there were more industrial casualties at home than military fatalities.

Visitors can tour a number of permanent exhibits and, on most Fridays, can chat with a real-life Home Front worker to learn more about the time period from someone who experienced it first hand. After finishing at the museum, be sure to check out the rest of Richmond, which still has a number of intact buildings from the time period as well as one of the last remaining victory ships, the SS Red Oak Victory.

Mummmers // Shutterstock

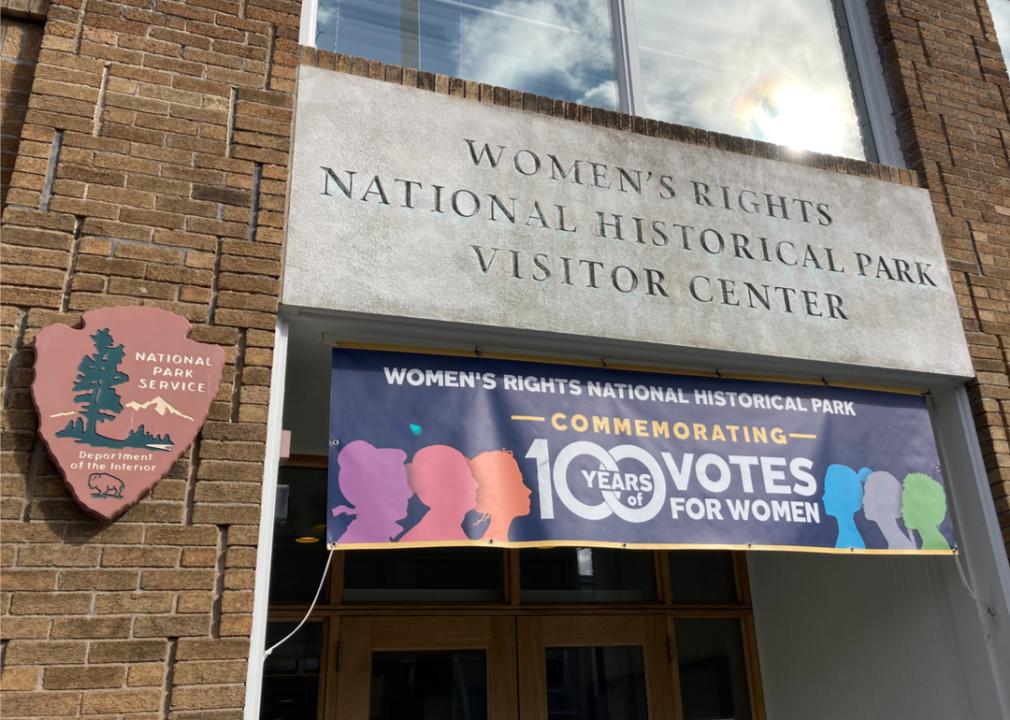

Women’s Rights National Historical Park

– Seneca Falls, New York

– Visiting info: Park grounds are open Dawn to Dusk

On July 19, 1848, the first women’s rights convention began at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. Here, activists unveiled the Declaration of Sentiments, which argued for women’s equality and suffrage, and was signed by 68 notable women and 32 men, including the movement’s leader, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

To this day, Seneca Falls is regarded as the birthplace of American feminism. The Women’s Rights National Historical Park, located in the area, tells the story of this conference as well as women’s subsequent decades-long fight for equal treatment. Visitors can listen to outdoor, ranger-led talks, wander through a handful of permanent exhibits, and tour a number of historically significant buildings like Wesleyan Chapel and Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s house (which she referred to as “the center of rebellion”).

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

Ida B. Wells-Barnett House

– Chicago, Illinois

– Visiting info: The House is a private residence and not open to the public

Born enslaved in 1862, Ida B. Wells-Barnett would go on to be arguably one of the most important journalists, activists, and leaders of the 19th and 20th centuries. She advocated for anti-lynching laws, successfully integrated the U.S. suffragist movement, and helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

A true force to be reckoned with, Wells-Barnett moved to this home in Chicago in 1919 with her husband, attorney, and fellow civil rights activist, Ferdinand L. Barnett. The home remains a private residence and is not open to the public, but folks wishing to pay tribute to the leader can still make a point to stop by, take a photo of the outside, and send a “thank you” for her activism. The home is also a stop on a larger civil rights travel itinerary called the “We Shall Overcome” tour.

Bettmann // Getty Images

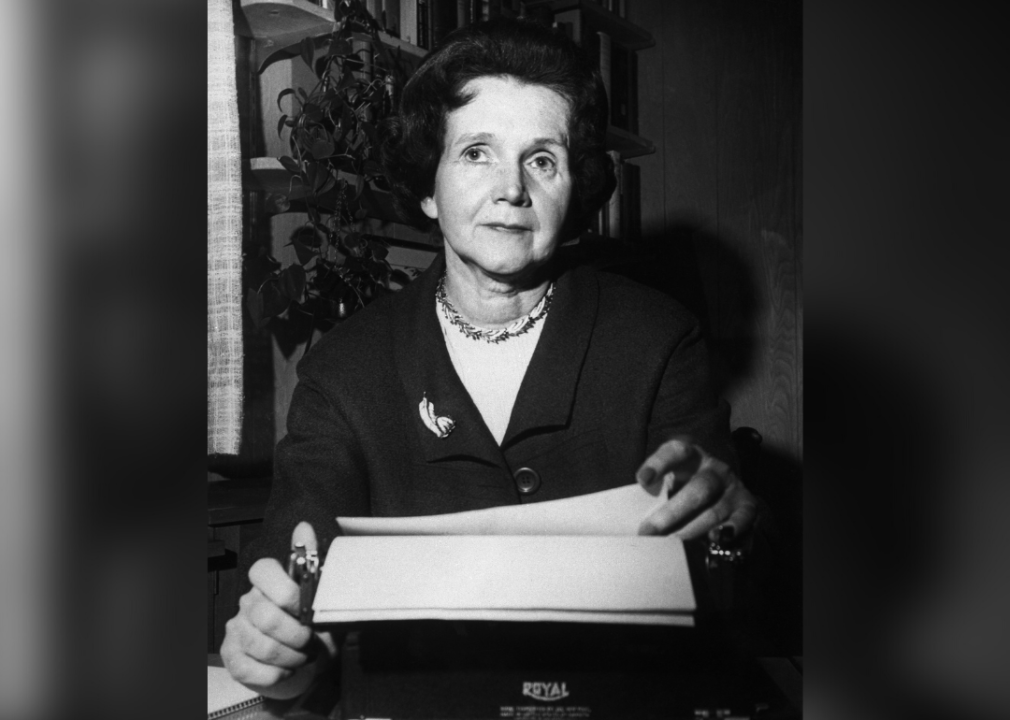

Rachel Carson House

– Silver Spring, Maryland

– Visiting info: Occasionally open to the public

An environmental activist, Rachel Carson changed the way Americans perceive their relationship with the natural world. A former member of the Department of Interior, Carson released a book in 1962 called “Silent Spring” that, among other things, detailed how our indiscriminate use of pesticides was ruining the environment. Her lyrical and deeply researched writing generated a massive uproar, which resulted in the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

This Silver Spring home, which she designed and moved into in 1956, is now the headquarters and library of the Rachel Carson Landmark Alliance. This library seeks to honor Carson’s legacy and continue her environmental work. Given the home is a working office, it is not always open to the public, though occasionally outsiders can snag a tour, attend a lecture in the space, or even luck out with an open house.

James Kirkikis // Shutterstock

Cherry trees at the National Mall and Memorial Parks

– National Mall, Washington, D.C.

– Visiting info: Open year-round to the public

In 1910, the Japanese government made a gift of about 2,000 cherry blossom trees to the United States. The flowering saplings, sent over as a gesture of friendship, were set to be planted in the newly established Potomac Park.

While the whole transaction seemed simple enough on the surface, it actually came on the heels of years of work of one Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. In the late 1800s, Scidmore traveled to Japan, where she fell in love with the trees and began advocating for the U.S. to acquire some of their own to beautify the nation’s capital.

Finally, in the early 1900s, she got First Lady Taft to agree to the plan, and things were set in motion. Today, there are over 4,000 cherry blossom trees in Washington D.C., and while they can be enjoyed year-round, they are perhaps most beautiful in late March when they are in full bloom and the National Cherry Blossom Festival takes place.

DCStockPhotography // Shutterstock

Star-Spangled Banner Flag House

– Baltimore, Maryland

– Visiting info: Tuesday to Saturday: self-guided tours from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

It was almost unheard of, in the early 1800s, for a woman to buy or own property of her own. But Mary Pickersgill, a flagmaker and seamstress, bought a Baltimore home in 1820 with her earnings. Best known for creating the first version of the American flag—with 15 stripes and 15 stars, representing the 15 states of the union—Pickersgill was incredibly successful, and her creativity and entrepreneurial nature would give the country its most recognizable symbol.

Her home has since been turned into a museum, and visitors can embark on self-guided tours of the well-preserved rooms and artifacts. Among the many things and people you’ll learn about at the museum is Grace Wisher, the often-overlooked Black indentured servant who helped Pickersgill with the creation of the Star-Spangled Banner.

Roy Rochlin // Getty Images

Ruth Bader-Ginsburg monument

– New York, New York

– Visiting info: Open year-round to the public

New York is a city teeming with statues of some of history’s most notable figures. Of the more than 150 life-sized bronze and stone sculptures that dot the boroughs, only five of them depict women. This underrepresentation—which is true of public monuments around the world, not just in New York—is changing.

In 2020, a statue of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second female justice elected to the Supreme Court of the United States, was unveiled in her native Brooklyn. Located in the heart of the borough, the statue earned RBG’s approval before her death in 2020 and sees her portrayed in a “dignified” manner. Throughout her career in law, Bader-Ginsburg fought tirelessly against gender discrimination and argued several landmark cases on gender equality, becoming a champion for women’s rights.

Jonathan Newton /The Washington Post via Getty Images

Tubman Byway

– Church Creek, Maryland

– Visiting info: Visitor Center is open Tuesday-Sunday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

An activist, abolitionist, suffragist, and the first Black woman to serve in the U.S. military, Harriet Tubman is arguably one of the most important figures in women’s history and Black history.

Born enslaved, Tubman escaped to the North, and to freedom, in 1849. Over the next few years, she helped an estimated 70 people escape their enslavement through the Underground Railroad, never losing a “passenger” and earning herself the nickname “Moses.” She later became a spy for the Union Army during the Civil War, led the raid on the Combahee Ferry, opened a home for aging Black seniors, and protested as part of the suffragette movement.

Today, you can follow some of Tubman’s footsteps by traveling along the 125-mile Tubman Byway, which goes from Maryland’s peninsula to Philadelphia. While the tour is self-guided, there are a number of educational stops along the way, including the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitors Center, which allows you to get a better understanding of how this woman lived and labored, and the horrors she fled from.

James R. Martin // Shutterstock

Mary McLeod Bethune House

– Daytona Beach, Florida

– Visiting info: On the campus of Bethune-Cookman University

Mary McLeod Bethune was a civil rights and women’s rights activist, an educator, and a presidential adviser. In 1904, she opened the Daytona Beach Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls in Daytona Beach, Florida, which eventually merged with an all-boys school called the Cookman Institute to form the Bethune-Cookman College, one of the country’s first historically Black colleges.

Outside of her pioneering work in education, Bethune served as an adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, started the National Council of Negro Women, and led voter registration drives all around the country. Her home in Daytona, which she moved into in 1913, has been preserved—nothing has changed since Bethune’s death in 1955. Visitors can walk through sections of the house, learning about the life story of this woman, as well as the impact she had on both gender and racial equality.

Alex Wong // Getty Images

Month of events from Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum

– Washington, D.C.

– Visiting info: Online and in-person events

In preparation for an eventual Women’s History Museum, the Smithsonian Institute has begun the American Women’s History Initiative. The project aims to highlight women’s roles in the country’s history, as their stories are often overlooked and aren’t widely told.

While the physical building isn’t expected to open for another 10 years, interested parties can attend a host of online and in-person (at other Smithsonian branches and cultural centers) events that cover everything from women’s discoveries in science to their accomplishments in art and even biographical deep dives. Additionally, a collection of objects, in categories ranging from activist to work, can be viewed online, accompanied by detailed descriptions that place the artifacts in the wider context of the nation’s history.

[Pictured: Life-size 3D-printed statues honoring women in STEM are seen at the Enid A. Haupt Garden outside the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, D.C.]

This story originally appeared on Bounce

and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.