Secret memoir may contain new proof against Carolyn Bryant Donham in the Emmett Till case. Is it enough to convict her?

Published 11:18 am Thursday, July 14, 2022

By Jerry Mitchell

Mississippi Center For Investigative Reporting

The secret memoir by the 88-year-old white woman at the center of the Emmett Till case contains new proof she is lying about the night he was killed, said the retired FBI agent who investigated the 1955 murder.

A grand jury should hear this information along with additional information collected by authorities, Dale Killinger said after reading the memoir. “I always err on the side of a group of citizens hearing evidence and weighing it.”

Carolyn Bryant Donham’s memoir, obtained by MCIR, constitutes new evidence that a Mississippi grand jury never heard when it declined to indict her on manslaughter charges in 2007, he said.

But convincing Mississippi authorities to do so is another matter. In a statement, Michelle Williams, chief of staff for Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch, called Till’s murder “a tragic and horrible crime, but the FBI, which has far greater resources than our office, has investigated this matter twice and determined that there is nothing more to prosecute.”

Donham’s memoir remains sealed in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill until 2036. But through a source, MCIR has obtained a copy of that single-spaced 109-page memoir, which contradicts her original statement to her husband’s defense lawyer, Sidney Carlton.

In that original statement, Donham — then Carolyn Bryant — said when her husband, Roy Bryant, brought Till to her, he “was scared but hadn’t been harmed. He didn’t say anything. Roy asked if that was the same one, and I told him it was not the one who had insulted me.”

That is far different from her memoir, I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle, which portrays Till as fearless and her as frightened. After she denied Till was the one at the store, she claimed he “flashed me a strange smile and said, ‘Yes, it was me,’ or something to that effect. … He didn’t act … scared in the least.”

Michael Whelan, a psychologist who grew up in Sumner and walked past the 1955 Till trial on the way to school, said he can’t imagine a 14-year-old Black youth from Chicago being dragged off by rednecks in the middle of the night and being unafraid.

The memoir, he said, contains “a whole lot of things that don’t have the ring of complete truth.”

Davis Houck, co-author of Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press, said Donham’s claim sounds like it was ripped from William Bradford Huie’s lie-filled Look article, which depicted Till as fearless to the end.

“The idea that Till would essentially out himself in front of his kidnappers and would-be killers,” he said, “is beyond absurd.”

Killinger said Donham’s claim in her memoir contradicts what she told him in 2005 — that Till said nothing when his kidnappers brought him to her.

During his investigation, he took the statements of two Black men. The first had been confronted by Bryant, who accused him of insulting Donham. She intervened and said it wasn’t him, and Bryant let him go.

The second man was walking home from Money after buying molasses for his mother, only to be picked up by Bryant and his half-brother, J.W. Milam. The man quoted Donham as saying, “That’s not the n—–! That’s not the one.”

The man said he was tossed from the truck and lost his front teeth when he hit the ground.

Those statements dovetail with the testimony of Till’s uncle, Moses Wright, who said Milam told him, “If this is not the right boy, then we are going to bring him back. If it is not the right boy, we are going to bring him back and put him in the bed.”

As Milam and Bryant left, Wright said they asked someone in the vehicle if this was the boy and that a voice replied, “Yes.”

“Was that a man’s voice or a lady’s voice you heard?” the prosecutor asked.

“It seemed like it was a lighter voice than a man’s,” replied Wright, who later told his son it was a woman’s voice.

Devery Anderson, author of Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement, said he believes that voice was Donham’s and that she identified Till.

Donham denies this, saying Till was brought to her at her family’s home in the back of Bryant’s Grocery. She denies identifying him.

“Would a reasonable person believe, given the fact her husband murdered him, that she did not identify Till?” Killinger asked.

Donham’s contradictions don’t end there.

In her Sept. 2, 1955, statement to her husband’s attorney, she said Till grabbed her hand and said, “How about a date?” When she walked away, she quoted him as asking, “What’s the matter, baby, can’t you take it?” before he went out the door and said, “Goodbye.”

This statement appears consistent with the testimony of Till’s uncle, Moses Wright, who quoted Milam as saying before he and others abducted Till, “I want that boy that done the talking down at Money.”

Anderson said, if Till had done more than talk, that would have been what his kidnappers told Wright.

Sixteen days after Donham’s statement to her husband’s attorney, Sidney Carlton, he announced to reporters that Till had “mauled” her — a claim she repeated from the witness stand while the jury was out.

By announcing this claim to reporters before trial, the defense ensured jurors heard about it, one way or another. Steve Whitaker confirmed this in his interviews with the all-white jury in 1963 for his master’s thesis at Florida State University.

Jurors had no doubt Bryant and Milam had carried out the crime, but Whitaker said they still acquitted the brothers because “they were racists who felt that it was permissible for any white person to kill any Black person.”

When the “not guilty” verdict came on Sept. 23, 1955, “we breathed a collective sigh of relief and joy,” Donham said. “I turned my head slightly and caught a glimpse of [Till’s mother] Mamie Bradley’s face, but Roy snatched my arm and told me to turn back around, to stop looking back at her.”

Except that Bradley wasn’t there. She didn’t stay for the verdict.

During his interviews with Donham, Killinger said she “stated on multiple occasions that she and Roy never discussed the kidnapping and murder.”

But her memoir tells a different story. After the sheriff showed up in 1955, Donham said Bryant told her in the kitchen that “they had only ‘whipped Emmett’ and let him go, so not to worry because everything would be okay.”

She said she later confronted Bryant about the 14-year-old’s death, asking, “How could you do such a thing?”

Bryant denied killing Till, and she said she replied, “But you are guilty. You could have walked away, but you didn’t. You could have stopped it, but you didn’t.”

Killinger said Donham did say Bryant told her years later that after he and the other men beat Till that he had begged to take Till to the hospital, but they refused.

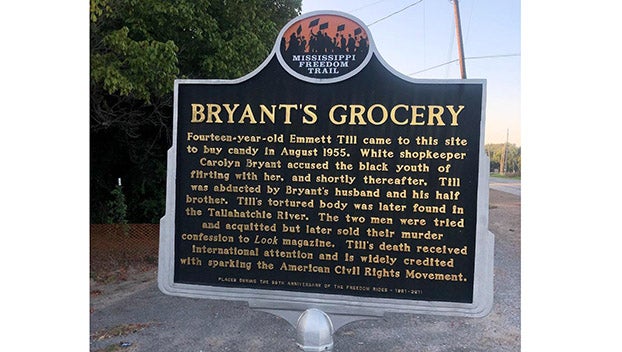

The one thing the couple did discuss? What happened inside Bryant’s Grocery the evening of Aug. 24, 1955.

In her memoir, Donham, who was 21 at the time of her encounter with Till, conjures the “black beast rapist” mythology, describing Till as a “man who appeared to me to be in his late teens or early 20s.”

In reality, Till had just turned 14.

She said when she held out her hand for Till to pay her for the candy, he grabbed her hand and said, “Don’t be afraid of me, I’ve been with white girls before.”

Then he asked for a date, and she feared he would “molest me or worse,” she said. “Never before, nor since, have I been that afraid.”

She said she jerked her hand free and dashed toward the main counter to get her husband’s pistol, but before she could reach it, he caught her with both hands on her hips, saying, “What’s the matter, baby? Can’t you take it?”

She said she struggled to get free again and quoted him as saying, “You needn’t be afraid of me, I’ve f—ed white women before.”

She said she screamed for help, “but no one responded. I was afraid and alone. I was shaking all over.”

Donham told the FBI that when Till touched her, she screamed for help — something she never mentioned in her original statement or testimony.

But none of Till’s cousins or anyone else at the store heard any such screams, despite the fact the store had screen windows.

“I was afraid and alone,” Donham said in her memoir. “I was shaking all over.”

Her original statement mentioned nothing about feeling afraid, only that she felt “insulted.”

Before Till could do more, Donham told the FBI “this other n—– came in the store and got him by the arm,” grabbing Till and pulling him out of the store.

In an FBI interview, that cousin, Simeon Wright, disputed her claim. He said he saw Till pay “for his items, and we left together. We walked out calmly. I didn’t think anything was wrong at the time.”

Till’s cousin, Wheeler Parker, said they never saw Till say or do anything to Donham inside the store that night. After emerging from the store, he said Till wolf-whistled at her. When someone said she had a gun, the cousins jumped into a car and sped away.

Donham claimed Till and his cousins left in a large tan luxury car: “You typically didn’t see that type of car in Money.”

Simeon Wright has said they fled in a 1946 black Ford after she pulled out a pistol.

In 2007, a Mississippi grand jury deliberated whether to indict Donham on manslaughter charges.

Killinger said state law held that if someone identified a person, knowing that person might be harmed — and then that person was killed —a manslaughter charge could be brought.

Killinger said she knew her mere identification of Till might bring him harm from her husband, and yet she did it anyway. Her memoir confirms those fears, saying her husband had a hair-trigger temper and that she was “terrified” for Till’s safety.

As an FBI agent investigating the case, Killinger presented evidence to a Leflore County grand jury in 2007. That included the statements of two Black men who identified Donham, saying they were freed after she told Till’s abductors they weren’t the ones.

The agent also introduced the testimony of Willie Reed, who saw Till in a truck with four white men and three Black men, later spotting Milam. Reed heard screams from Till’s beating.

Minutes before the grand jury began to deliberate, Killinger said District Attorney Joyce Chiles began to discuss the murder statute and how there was no evidence of murder.

What bothered Killinger was this was strictly a manslaughter case. “If you don’t have evidence of murder, why muddy the water and confuse a grand jury?” he asked.

He recalled an elderly Black woman finally standing and saying, “Why don’t you just let us vote? You do that with every other case.”

Prosecutors sent Killinger out, and more discussion ensued.

Gary Woody, who served on the 2007 grand jury, said he believed from the evidence that Donham “was a battered woman and would have done whatever he [her husband] asked her to do.”

Killinger said grand jurors never asked him if Donham had been battered. If they had, he said he would have told them that Donham insisted that Bryant didn’t batter or abuse her.

The retired FBI agent disagrees with the theory that Donham had no choice but to go along with her husband’s wishes. He pointed out that after Till’s murder, she had “every opportunity to change course, including after the acquittal, but she didn’t.”

For example, he noted that Donham identified Bryant’s brother-in-law, Melvin Campbell, as the one she was told fired the fatal shot, but she never told authorities this.

When grand jurors voted in 2007, they declined to indict Donham.

Killinger said there is much new evidence these grand jurors never heard — her original statement to Bryant’s lawyer (which the FBI first learned about in 2008) and her unpublished memoir, which surfaced in the FBI’s latest investigation.

Members of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation recently located the original 1955 warrant in the basement of the Leflore County Courthouse. That warrant called for the arrest of Donham, Bryant and Milam on kidnapping charges.

Back in 1955, authorities did arrest the men, but did nothing to Donham, saying “she’s got two small boys to take care of.”

Christopher Benson, co-author with the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. of the upcoming book A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on The Journey to Justice For My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till, told MCIR that finding the warrant is important to history. But the attorney and associate professor at Northwestern University said he believes it adds nothing to the criminal case.

Almeda Luckey, who voted with other grand jurors in opposing the indictment, said if she had known that Donham’s original statement contradicted her 1955 testimony, she would have voted to charge Donham with manslaughter.

Woody believes prosecution is impossible, but he confessed, “I don’t think this case is ever going to die until she dies.”

If a new grand jury did investigate, it would face plenty of hurdles. The two young Black men that Milam and Bryant thought might be Till are now dead. So are Moses Wright and Simeon Wright. So is Willie Reed.

“Without an admission by her or some other evidence that she [Donham] identified Till, it remains a very difficult manslaughter case,” said Matt Steffey, professor of law at Mississippi College School of Law. “For all the inconsistencies, she denies identifying Till in all the statements.”

While there could be enough evidence for an indictment, he said, there “might not be enough to sustain a conviction.”

Mississippi lawyer Jill Collen Jefferson, founder of Julian, a civil rights and international human rights organization that has investigated past and modern-day lynchings, disagreed, saying she believes Donham’s memoir constitutes new evidence that makes a conviction possible.

To be found guilty of manslaughter, Donham must have acted with “conscious disregard” and “should have known” her actions would lead to violence against Till, Jefferson said.

That, she said, is proven by Donham’s memoir, where she wrote that she didn’t say anything about what happened in the store to Bryant because he had a “hot temper” and “I was worried … he’s gonna go find and beat him up. … I was afraid of what they would do.”

In addition, the two prior abductions of Black men show that Donham knew that if she identified Till, harm might follow, Jefferson said. “She marked Emmett for death. It does not matter if she knew or didn’t know they would kill him. What matters is that she should have known it was possible.”

In her memoir, Donham shifts the blame to others.

“She puts the blame on Emmett Till in her memoir to take it off herself,” Jefferson said. “It is clear that he had to have been identified for Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam to know it was him, otherwise they would have let him go like they did the other two young Black men they’d harassed or assaulted.”

Donham blames her sister-in-law, Juanita Milam, who was babysitting the children. In the memoir, Donham says her sister-in-law never heard her screams and never saw Till, but Donham later accused her of identifying Till at Moses Wright’s home, saying, “She’s the only woman who could have identified him other than myself.”

In an FBI interview, Milam said she wasn’t at the store that night, that she didn’t babysit for Donham and that she suspected Donham “thought this wild story would make Roy take care of the store instead of leavin’ her with the kids and the store.”

In the memoir, she said, Donham even points her finger at the Till family, wishing they had returned him to Chicago.

After interviewing Donham, Killinger spoke with FBI’s behavioral science experts, who concluded that her being willing to admit she identified Till is “deep inside her. We don’t know if she’ll ever let it out.”

Author and journalist Wright Thompson said Donham’s “insistence on carrying her lies about Emmett Till beyond the grave is a reminder that the battle between truth and erasure remains ongoing and vital. The woman who emerges on the memoir’s pages is both haunted and defiant.”

Anderson doesn’t believe Donham supported any violence toward Till. “Her personality was one,” he said, “where she couldn’t handle conflict or moments like this.”

One relative, he said, remarked that Donham “fell to pieces after this happened and had to take sedatives.”

But a different side of Donham emerges from the memoir.

In the wake of the 1955 trial, she dared her mother-in-law to take the $60 she received as a gift: “She was going to be tied up with a little hell cat if she tried taking my money. I know at that moment that she did believe the old saying that ‘dynamite comes in little packages’ and she was about to open up a whole truckload of it!”

The Justice Department dove back into the case after author Timothy Tyson claimed in his 2017 book, The Blood of Emmett Till, that Donham had recanted her testimony when she claimed that Till had attacked her.

In December 2021, the Justice Department and the Leflore County District Attorney’s office closed the case after she “denied recanting her previous testimony and the professor who claimed she made such a confession was unable to substantiate his claim and made inconsistent explanations to the FBI,” according to the Mississippi attorney general’s office.

Justice Department officials and District Attorney Dewayne Richardson met with Till’s closest surviving relatives in Chicago when the department closed the case.

In March, department officials and Richardson met with other members of the Till family.

Till’s cousin, Deborah Watts, said another grand jury needs to investigate, because Donham has never been held responsible for identifying Till to his killers.

“I have no hate in my heart for her,” she said, “but the case is still an open case because there is no statute of limitations on murder.”

More than a century after Congress first debated legislation against lynchings, the bill passed, and the President signed it in March.

“The anti-lynching legislation bears Emmett Till’s name,” Watts said. “Now let’s get justice for Emmett Till.”

Lying to an FBI agent is a crime, but any false statements Donham made to Killinger more than a decade ago would be barred from prosecution, because perjury carries a five-year statute of limitations. If she made any false statements to the FBI more recently, the door for prosecution would remain open.

Jefferson said if the district attorney refuses to empanel a grand jury to hear the new evidence, the Till family should consider filing a criminal complaint to bring charges.

She lambasted Donham for blaming Till “for his own torture and execution. The U.S. has deported Nazi guards to face trial but has yet to prosecute Carolyn Bryant.”

Email Jerry.Mitchell@MississippiCIR.org. You can follow him on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

This story was produced by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for our newsletter.