Clay tablets and human skin: 10 special collections at universities

Published 8:05 pm Monday, July 18, 2022

Jose L Vilchez // Shutterstock

Clay tablets and human skin: 10 special collections at universities

Libraries have long represented the heart of college campuses, both architecturally and academically. In addition to being hubs for studying, communing with other students, and researching archival records, university libraries hold often-massive collections—Harvard has roughly 20 million volumes to its name.

University libraries and museums also frequently have special collections, often consisting of rare manuscripts or archival collections, which are sometimes donated to the university by a prominent alum or philanthropist. But many special collections hold more unique—or downright odd—contents.

To dive into the history of 10 special collections, Best Universities investigated the strange, remarkable, and occasionally shocking items kept by university libraries and museums across the country.

Special collections can provide insight into historical figures, document the stories of a niche, otherwise-overlooked subject, or illuminate the quirks of personal collecting. These collections run the gamut from a rare first edition of “The Book of Mormon” at Dartmouth to a prodigious snowglobe collection at the University of Cincinnati, and even a collection of materials on puppetry and clowns housed at UC Santa Barbara.

Continue reading to find out which universities have some of the most unique collections.

![]()

Stokkete // Shutterstock

Forgeries

The Frank W. Tober collection at the University of Delaware contains books on the Napoleonic era and the French Revolution, the history of papermaking, and most famously, a sizable collection on literary forgery. The collection includes a number of actual forgeries, as well as secondary sources such as historical accounts and reference materials.

Major historical forgeries like the Shakespeare forgeries of William Henry Ireland and the work of British forgers Thomas J. Wise and H. Buxton Forman are documented in the collection. The Tober collection also includes texts on counterfeiting, literary hoaxes such as Clifford Irving’s notorious falsified “autobiography” of Howard Hughes, and the science behind identifying forgeries.

LEE SNIDER PHOTO IMAGES // Shutterstock

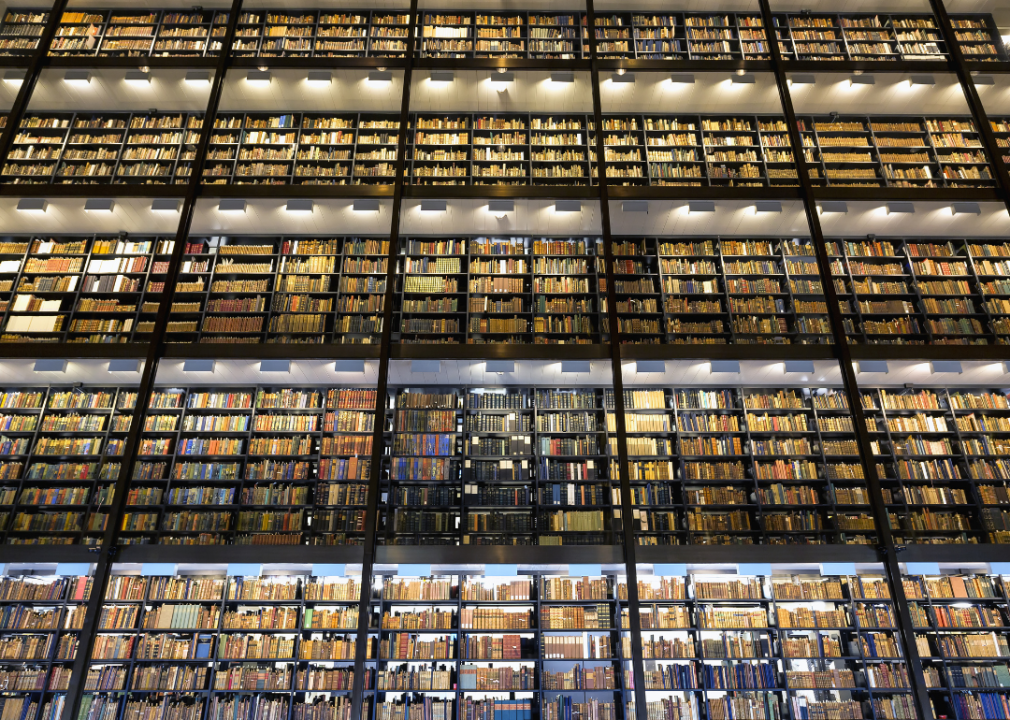

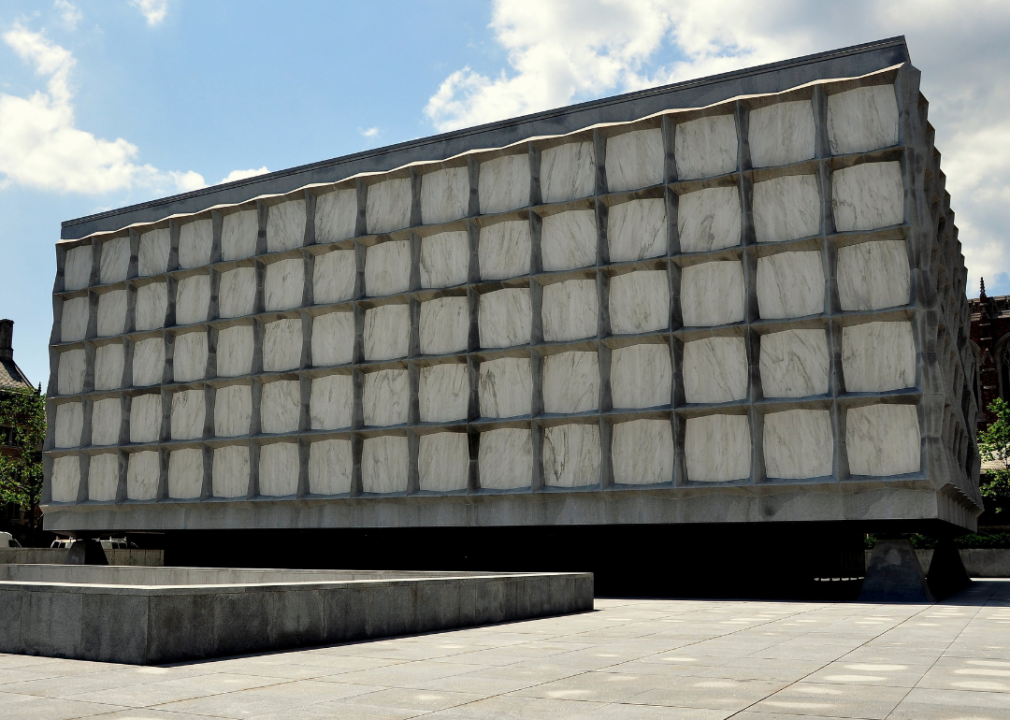

Voynich Manuscript

Housed in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Voynich Manuscript is often referred to as “the most mysterious manuscript in the world.” The 15th-century book is written in an indecipherable code, referred to as Voynichese, that seems to mix elements of Roman, Glagolitic, Greek, and Gothic alphabets, also contains colorful illustrations of plants, naked women, astral charts, and zodiac symbols.

Though cryptographers and Medievalists have spent over a century trying to decipher the 240-page text, there has been no consensus around the meaning of the book. Theories about the Voynich Manuscript’s contents range from Renaissance-era women’s health manual to a scientific or even magical text, while some claim it was an elaborately designed hoax. The manuscript can be viewed online.

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock

Taxidermied animals

The Rhode Island School of Design’s Edna W. Lawrence Natural History Collection comprises over 80,000 natural specimens. Inside the Nature Lab are taxidermied moose, antelope, bobcats, and bears, as well as butterflies and insects, shells, and skeletons—both animal and human. Lawrence was a faculty member who taught nature drawing using specimens she collected herself over the course of five decades.

The Nature Lab was designed to allow students more tangible access to the natural world than traditional textbooks and photographs allowed, and to this day continues to allow students and faculty to borrow the natural objects, library-style.

Jay Yuan // Shutterstock

Historical texts on witchcraft

The Cornell University Witchcraft Collection is the largest in North America, with over 3,000 texts on witchcraft. The collection, which dates back to the 15th century, mostly focuses on the evils of witchcraft from a religious standpoint and considers its practice heresy. Many books are historical documentations of the European Inquisition and detail how those thought to be witches were punished.

The library also houses some books on demonology and the very first book to be published on witchcraft. There are even documents written by theologians who spoke out against the witch hunts, and court records from trials that contain firsthand testimony from those accused of practicing witchcraft.

The Witchcraft Collection also boasts over 600 movie posters and cinema memorabilia related to witches and witchcraft. This part of the collection is intended to help trace shifts around how people’s attitudes toward witches have changed over the years, as well as how witches have occupied the cultural imagination in various ways for centuries.

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock

Classic pigments

The Forbes Pigment Collection at Harvard University is home to over 2,700 color specimens used throughout history to create paints, dyes, and varnishes. The collection was started by Edward Forbes, who headed the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard for the first half of the 20th century. The famed art conservationist collected pigments from around the world to aid in dating and authenticating paintings.

The collection includes “Mummy Brown,” a brown color popular in the 18th and 19th centuries that was made from the resin used in ancient Egyptian mummy wrappings, and ultramarine, a rich blue made from Afghanistan-mined lapis lazuli, which was at one time so in-demand that it was more expensive than gold.

Today, the pigments are used by conservation scientists at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, and are sometimes sent to other art museums to aid in authentication and conservation work.

Joy Brown // Shutterstock

Books bound in human skin

Amongst the personal letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Walt Whitman’s copy of “Leaves of Grass” at the John Hay Library at Brown University are four anthropodermic books—or books bound in human skin.

There is some disagreement amongst historians over how common a practice it was to bind books using human skin. One believes it was a relatively common practice related to death penalty laws in 19th-century Scotland, which allowed for public dissection of bodies after their execution. Others estimate there are only about 50 known anthropodermic books worldwide.

At John Hay Library, one such book is a volume on human anatomy entitled “De Humani Corporis Fabrica.” The library’s collection also houses two human skin-bound copies of Hans Holbein’s grisly Renaissance-era woodblock print collection called “The Dance of Death.” The fourth anthropodermic book is a copy of Adolphe Belot’s 1870 novel “Mademoiselle Giraud, My Wife,” which is known for its homophobic depiction of a lesbian affair.

Dmitrii Sakharov // Shutterstock

Ancient cuneiform clay tablets

Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library holds one of the oldest collections of cuneiform clay tablets in North America, its holdings numbering over 600 tablets. Some of the oldest pieces in the collection can be traced back to the Third Dynasty of Ur (20th-21st century B.C.), while others are from the Sumerian and Old Babylonian periods.

Many of the tablets were donated to the university in 1896, and are thought in part to be the product of archaeological looting. The collection also houses Plimpton 322, one of the most famous Old Babylonian mathematical tablets. The tablet is known for containing evidence of proto-trigonometry with its table of Pythagorean triples.

Kit Leong // Shutterstock

Showgirls

The Showgirls collection at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas’ Library documents the city’s history and living legacy through the medium of the show: a unique blend of vaudeville, burlesque, cancan, opera, and speakeasy entertainment that has come to define Las Vegas.

The Showgirls collection consists of elaborate costume drawings, production notes, and even photographs that include showgirl acts with performers like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Jerry Lewis. The collection also contains historical accounts of the Las Vegas hotel scene and the evolution of the city from a quiet desert town to the city it would become.

Ken Wolter // Shutterstock

Miniature books

Indiana University’s Lilly Library houses the largest collection of miniature books in the U.S., with over 16,000 items. Much of the collection is made up of the mini books of Ruth Adomeit, who collected 8,000 tiny volumes under 2.5 inches tall.

Adomeit gathered her enormous collection over the course of almost 60 years and was so passionate about mini books that she started a publication called the Miniature Book Collector and co-founded the Miniature Book Society. The collection includes mini ancient cuneiform tablets and addresses given by Abraham Lincoln.

Albert Pego // Shutterstock

Magical amulets

Sterling Memorial Library houses Yale’s legendary Babylonian Collection, where, amongst scrolls and maps, are 74 Greco-Roman-Egyptian amulets, thought to contain magical powers.

Made of stone or metal, the small amulets are inscribed with images of Greek and Egyptian gods and their names, as well as magically powerful phrases in Greek. Papyri discovered from the same period details how the amulets were to be used during magic rituals, and that they were sometimes worn as jewelry. They represent the overlap of magic and religion in ancient polytheistic practices.

This story originally appeared on Best Universities and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.