10 leaders from the past century who fought for workplace inclusion

Published 3:15 pm Wednesday, July 20, 2022

PhotoQuest // Getty Images

10 leaders from the past century who fought for workplace inclusion

A little more than a century ago, the rough edges of today’s labor market began to take form. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Industrial Revolution precipitated a boom in the mass production of goods by machines and the hiring of factory workers needed to operate and maintain such a large output.

Still, for women and people of color who did this work for pennies on the dollar in comparison to their white male counterparts, an air of unfairness permeated within factory walls and elsewhere. This imbalance led to multiple movements for workplace inclusion and fairness.

Using research from across the internet, Kazoo compiled a list of leaders who you may not know left a lasting legacy for workplace inclusion in the 20th century. This list is sorted alphabetically by last name.

Despite strides made for workplace inclusion in the past century, wage gaps still exist. According to the Department of Labor, women still only make 76 cents for every dollar a man makes; the same exists between white and Black workers. Hispanic workers make even less at 73 cents for every dollar a white worker makes, showing that there is still progress to be made before each and every American reaches true labor equality.

Read on to learn about 10 leaders who endeavored to bring workplace inclusion to the fore.

![]()

Chris Maddaloni // Getty Images

Betty Dukes

In 2001, Walmart greeter Betty Dukes filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of as many as 1.5 million female workers, including herself. The reason for her suit was simple: gender discrimination. At the time of her suit, about 3 in 4 of the Walmart sales workforce were women, and Dukes noticed that most promotions at her store and others went to her male colleagues. In fact, she claimed she was never given a promotion opportunity during her six years working there up to that point.

To her disappointment, after a decade in the courts, Betty Dukes v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., was thrown out by the Supreme Court in 2011. In its 5-4 majority opinion, the conservative justices were not convinced by anecdotal evidence and statistical data portraying Walmart as a boys club. The majority opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, also added that the women in the class action failed to prove they had the same issues in common.

The result made it more difficult for workers to bring big discrimination suits against the large corporations they work for based on sex and race. Even so, Dukes, who passed away in 2017, inspired female Walmart workers around the country to bring smaller suits in their own districts, as in the 2013 case of Sandra Ladik et al. v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. in Wisconsin.

Emma McIntyre // Getty Images

Dolores Huerta

Arguably one of the most well-known and influential labor activists of the 20th century, Dolores Clara Fernandez Huerta was a leader of the Chicano civil rights movement. Born in 1930, Huerta was greatly influenced by the hard work of her mother, Alicia Fernandez, who worked as a waitress and in a cannery until she was able to buy and operate a hotel and restaurant in California. Dolores was also influenced by the discrimination her family experienced, including her brother, who was beaten in 1945 by a group of white men for wearing a zoot suit, a loose-fitting suit popularized by the Latino youth culture of the time. This was only two years after the infamous Zoot Suit Riots of 1943.

After receiving an associate teaching degree from the University of the Pacific’s Delta College, Huerta found her true calling in the 1950s while briefly teaching in schools. She noticed many hungry farm children coming to school during her tenure and decided she could do more to help this community by organizing farmers and farm workers. Starting in 1955, Huerta co-founded the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization, an establishment that drove voter registration and advocated for economic improvements for Hispanic people in the Stockton community.

From there, Huerta founded the Agricultural Workers Association, met activist César Chávez, and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which preceded the United Farm Workers Union in 1962, of which Huerta served as vice president until 1999. Fighting for agricultural workers’ unemployment and health care benefits and safer working conditions, among other conditions, Huerta led boycotts and strikes of grape workers, resulting in a successful workers contract and union contract for that industry.

In 1973, another Huerta-led grape boycott led to California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, which allowed farm workers to form unions and bargain for better pay.

ImageCatcher News Service // Getty Images

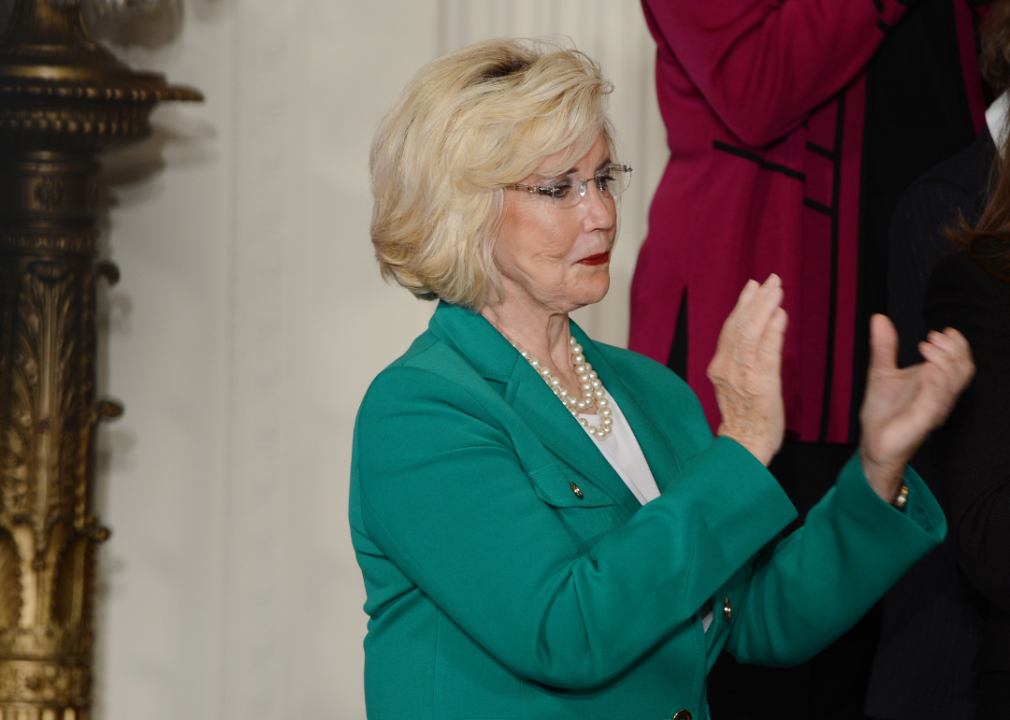

Lilly Ledbetter

Born Lilly McDaniel in Jacksonville, Alabama, in 1938, Ledbetter married Charles Ledbetter out of high school and together had two children. In 1979, Ledbetter was hired by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company to work as an overnight supervisor, a position traditionally held by men, and when she started she made the same wage as the men as well. For 19 years she blossomed at the company, even receiving a Top Performance Award. Just before retirement, however, an anonymous source slipped a note into her mailbox listing the salaries of her male coworkers, all receiving thousands more in salary despite performing the same exact job.

Ledbetter, then in her late 60s, filed a formal complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission alleging pay discrimination. As her complaint and later her lawsuit worked its way through the courts, Goodyear reassigned the near-retirement Ledbetter to stringent duties like lifting heavy tires. Though she won her initial lawsuit and $360,000 in back pay and earnings using Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Goodyear appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court and won in a 5-4 decision, causing Ledbetter to lose her monetary reward. The Supreme Court stated that disputes over pay over 180 days were not valid, and therefore her case had no merit.

Unfazed, Ledbetter has lobbied since then for equal pay, proving victorious in 2009 when then-President Barack Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act into law on Jan. 29, 2009. This law allows pay discrimination claims on the basis of sex, race, national origin, age, religion, and disability to accrue every time an employee receives a discriminatory paycheck rather than sticking by the timeline of management decisions made to pay that employee less.

Bromberger Hoover Photography // Getty Images

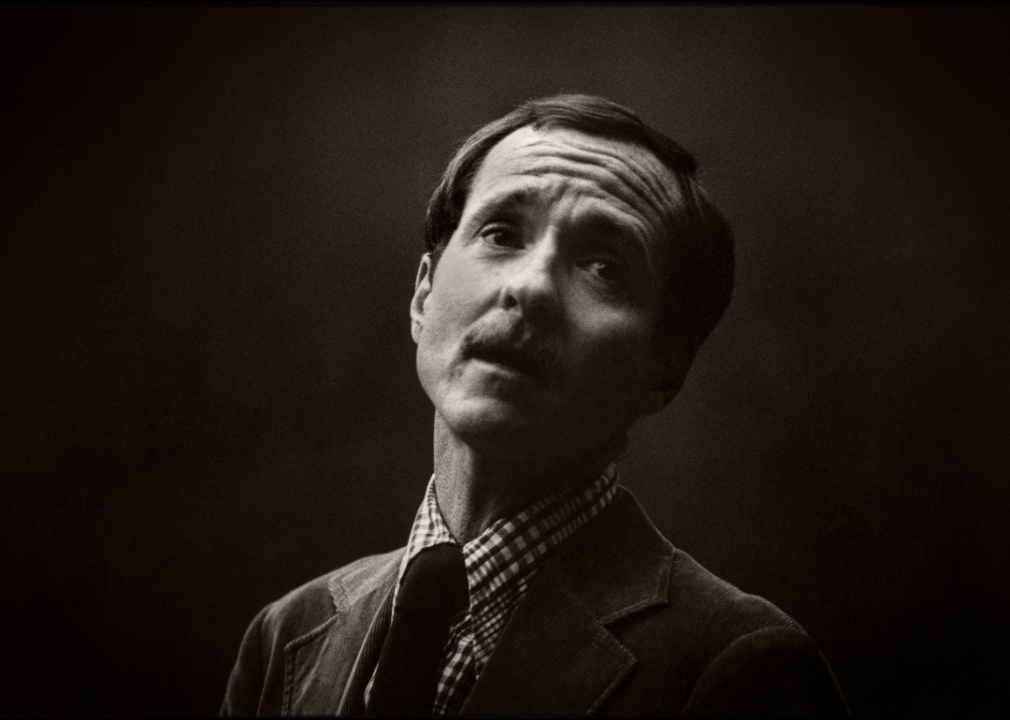

Leonard Matlovich

On March 6, 1975, Air Force Sgt. Leonard Matlovich changed the course for LGBTQ+ people in the military when he wrote a letter to his commander coming out as gay. A year earlier, the Bronze Star and Purple Heart recipient read a story in Air Force Times mentioning that a gay rights activist named Frank Kameny was looking for someone in active service to test the military’s ban on gay service members.

So, on Sept. 8, 1975, the then-closeted Matlovich bravely appeared on the cover of Time magazine in uniform with the headline, “I Am a Homosexual.” This instantly made him one of the most visible members of the gay rights movement, and that was the point: He wanted to take the military infrastructure to the Supreme Court, much like Brown v. Board of Education forced the hand on segregation.

Unfortunately, his case never made it to the Supreme Court, and the Air Force gave him a general discharge, well below the honorable one he rightly deserved. Although Matlovich passed away in 1988, what he was fighting for would become reality in 2011 when the 18-year ban known as “don’t ask, don’t tell” was repealed, allowing LGBTQ+ service members to serve openly in the military.

Imagno // Getty Images

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins was a workers’ rights advocate who became the first woman to ever serve in the presidential cabinet when she became the U.S. secretary of labor, serving under former President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Born into a privileged family based in Boston, Perkins grew up in a strict and conservative household where she was rarely exposed to people outside her station and was told that people were poor because poverty was the result of alcohol or laziness.

Perkins, however, was much more sympathetic to the struggles of the average American worker. While enrolled at Mount Holyoke, she took a course in economic history that required students to visit factories along the Connecticut River in order to observe the working conditions there, cementing her desire to affect change, particularly for women and child workers.

After college, during an outing in New York’s Washington Park, Perkins witnessed 47 people, mostly young women, jump to their deaths from the eighth and ninth floor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which was engulfed in flames. Both the working conditions and the emergency exit system at the factory were unsafe, ultimately leading to 146 deaths. With the help of President Roosevelt, Perkins helped enact many changes to the operations of facilities such as Triangle as the executive secretary of the Committee on Safety.

Later, Perkins served on the New York State Industrial Commission, later becoming the industrial commissioner. As secretary of labor, Perkins is most famous for helping Roosevelt usher in the New Deal. Perkins is largely credited for instituting the 40-hour workweek (as a key originator of the Fair Labor Standards Act), minimum wage and unemployment compensation, worker’s compensation, the end of child labor, and Social Security.

Denver Post // Getty Images

Esther Peterson

Esther Peterson made history as an advocate for workers’ rights. Growing up in a conservative family in Utah, Peterson graduated from Brigham Young University and moved to New York City where she married Oliver Peterson, with whom she relocated to Boston in 1932. There, she taught at a prep school and volunteered at the Young Women’s Christian Association.

One day at the YWCA, none of her students showed up for class. The reason? They were all on strike. While visiting one of her students, a 16-year-old named Eileen, she noticed that the girl and her siblings were all working to make dresses. The youngest, a 3-year-old, helped sort bobby pins. They were all trying to help their sister reach her quota: $1.32 per dozen dresses. Those in charge changed part of the dress design, making it more complicated to finish, but did not increase the rate of pay.

It was then Peterson joined her first picket line, inspired by the sisters. She later became an organizer for the American Federation of Teachers, joined the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, and was appointed head of the Women’s Bureau in the Department of Labor under President John F. Kennedy in 1961. For the next two decades, she worked tirelessly to improve the lives of working women, including making efforts to establish equal pay, daycare access, and racial equity for Black women in the workforce, including ushering in the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

Bettmann // Getty Images

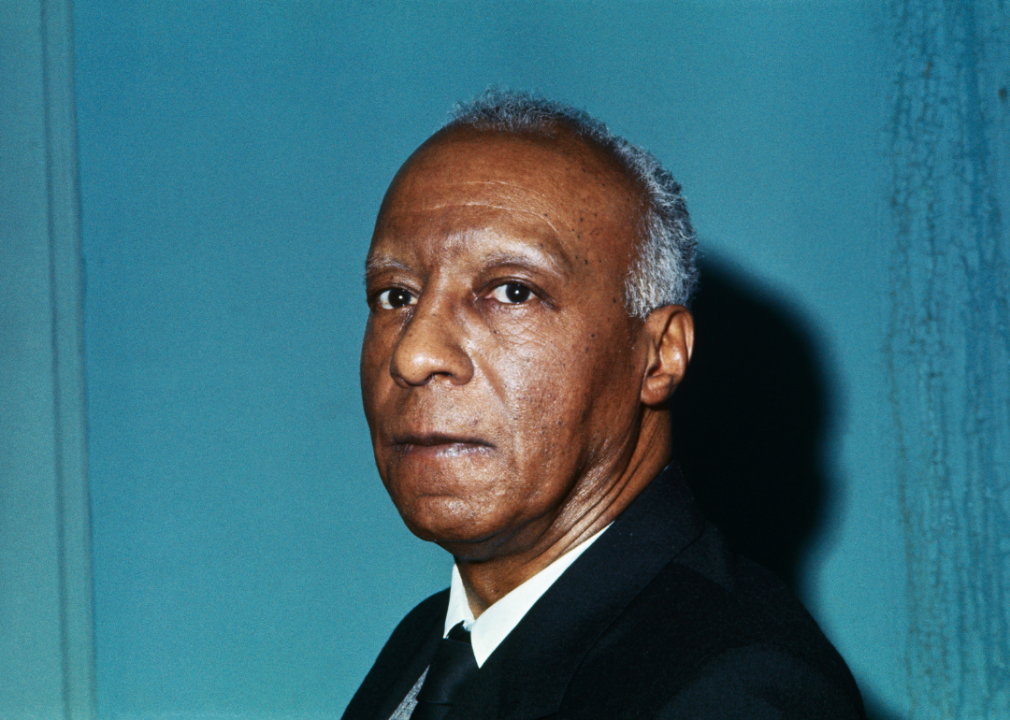

A. Philip Randolph

Born in Crescent City, Florida, in 1889, Asa Philip Randolph helped improve the lives of millions of African American workers, eventually inspiring the nonviolent protest strategy of the civil rights movement. A socialist, Randolph, along with his friend and close collaborator Chandler Owen, published a magazine called the Messenger, which focused on socialist issues and class consciousness in the African American community.

In June 1925, he was approached by the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to spearhead its organization, and for the next 10 years, he led a campaign to organize a union of Pullman train porters. His efforts were successful; Randolph called it the “first victory of Negro workers over a great industrial corporation.”

Later, he became the most widely known spokesperson for Black workers in the United States and successfully pressed President Franklin D. Roosevelt to ban discrimination against Black workers in the defense industry, when Roosevelt had no intention of doing so. Randolph called for “10,000 loyal Negro American citizens” to march on Washington D.C., and when numbers approached 100,000, Roosevelt relented, declaring, “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” He was named the chair of the 1963 March on Washington, and in 1964 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Patrick A. Burns // Getty Images

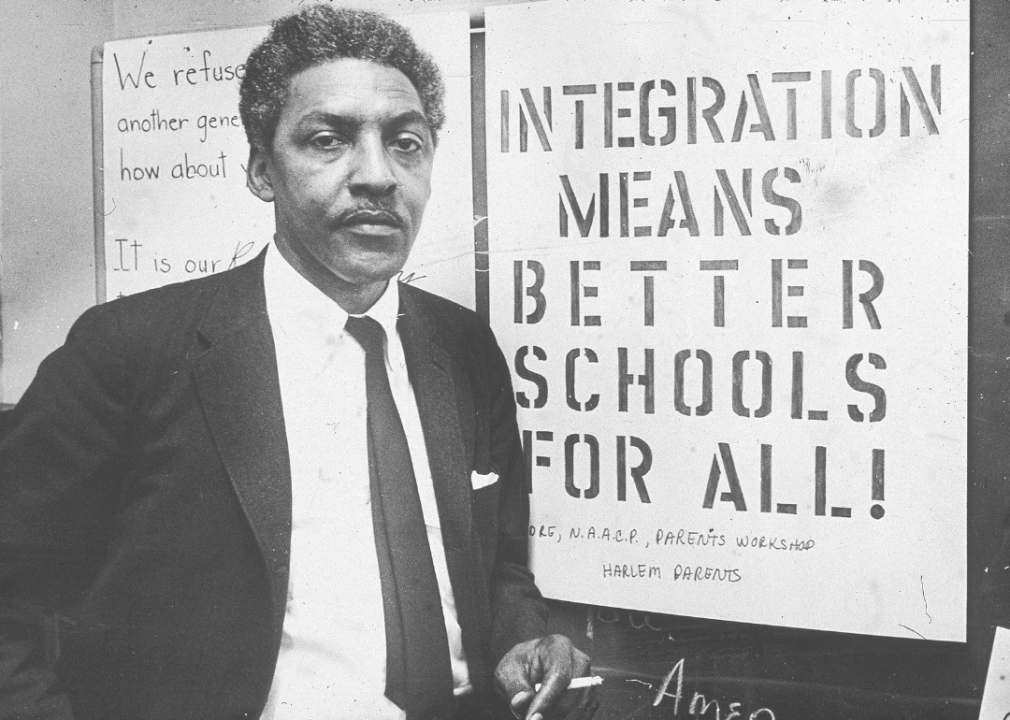

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin helped organize and lead key protests across the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. One of 12 children raised by Quaker grandparents, Rustin met Black community leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and Mary McLeod Bethune as a result of his grandmother’s participation in the NAACP. After a stint at City College of New York in the 1930s, Rustin was appointed youth organizer of the proposed 1941 March on Washington (by A. Phillip Randolph), leading workshops for nonviolent direct action and protest that became models for the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

During the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-1956, Rustin advised Martin Luther King Jr., whom Rustin is largely credited with instilling the knowledge of nonviolent techniques in the way of Gandhi. Earlier in life, Rustin had gone to India to study the Gandhian philosophy of nonviolence; it was with this knowledge that Rustin was appointed deputy director of the 1963 March on Washington, and under his tutelage, 250,000 participants made it to Washington D.C. for the historic event.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Crystal Lee Sutton

Crystal Lee Sutton, née Jordan, was a union organizer whose story eventually became cinematic history. When she was 33, she worked at textile company J. P. Stevens’ plant in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. Making about $2.65 per hour folding towels, Sutton decided to approach other workers in the plant to unionize.

Her fight for higher pay and better working conditions was met with hostility from management. After months of aggressive treatment by her superiors in retaliation for her attempts to organize plant workers, the company fired her. It was there, as she was being walked out, that she wrote on a piece of cardboard the word “union” and stood on a chair to show it to her colleagues. The inspiring moment caused her coworkers to stop their machines that very second and put up the peace sign in silent solidarity.

About a year later, a union representing 3,000 employees at seven separate plants was formed—the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. Her unionization efforts were immortalized on film in 1979 when Sally Field depicted her in the movie “Norma Rae,” for which Field earned the Best Actress Oscar. The film subsequently earned a place in the U.S. Library of Congress for being considered “culturally, historically, or aesthetically” significant and was also selected to be preserved in the National Film Registry.

Bryan Pollard // Shutterstock

William Monroe Trotter

Willam Monroe Trotter was a Black Boston-area newspaper editor and real estate businessman. Born to a wealthy Massachusetts family, Trotter was educated at Harvard University and set a precedent at the Ivy League school by being the first man of color to earn a Phi Beta Kappa key.

In 1914, Trotter, by then an influential and prominent voice in the Black community, met with Woodrow Wilson as part of a delegation of African American leaders to confront the segregation and bigotry happening in the postal service. Reports of Black postal workers being unable to receive a promotion, working in poor, cramped conditions, and even in one case being denied access to the common lunchroom were just a few examples of the ill-treatment that took place under the segregationist leadership of Postmaster Gen. Albert Burleson. Burleson instituted a new rule requiring federal applicants to the postal service to submit a photograph, which helped officials to filter out Black applicants completely.

The publicity that Trotter’s tense meeting with Wilson generated, in tandem with these unfair policies and other factors, helped spark the passion for equal treatment that eventually became the civil rights movement.

This story originally appeared on Kazoo and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.