Your guide to the Bill of Rights and other constitutional amendments

Published 8:45 pm Thursday, September 8, 2022

Canva

Your guide to the Bill of Rights and other constitutional amendments

For more than a decade following the Revolutionary War, America was governed by the Articles of Confederation, which provided for only a weak and minimal federal government while allowing states to operate like individual sovereign countries. That was until 1787, when delegates of the Constitutional Convention signed the Constitution of the United States of America in Philadelphia.

Since then, the document has been altered 27 times through the amendment process provided by Article V of the Constitution itself. Requiring a two-thirds majority vote by both the House and Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the country’s state legislatures, amending the Constitution is no easy task.

The first 10 amendments to the Constitution are collectively called the Bill of Rights. Written by James Madison, the Bill of Rights puts specific limits on government power and enshrines specific personal liberties. With issues such as free speech and the right to possess and carry firearms seemingly unerring issues in today’s political climate, Stacker compiled a look at all 27 amendments to the Constitution in order to provide an overview of precisely what was at stake each time our elected leaders voted to amend America’s governing document.

![]()

Canva

Amendment I: Religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition

Year ratified: 1791

The First Amendment is the cornerstone of America’s basic liberties. It guarantees both the freedom of religion and, from religion, a free press, the freedom to assemble peaceably, to speak freely, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Aldaron // WIkicommons

Amendment II: Right to bear arms

Year ratified: 1791

Perhaps no part of the Bill of Rights is more hotly contested than the Second Amendment, which provides that “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The language of that statement has sparked fierce debates—in a country that suffers tens of thousands of gun deaths every year—over whether the framers meant that gun ownership is an individual right or that gun ownership is guaranteed only for regulated defense organizations.

Public Domain

Amendment III: Quartering of troops

Year ratified: 1791

Today, the Third Amendment has virtually no impact on our daily lives; it has been litigated less than any other amendment in the Bill of Rights, and the Supreme Court has never heard a case on it; however, when the framers wrote it, Britain’s long history of forcing its subjects to quarter (house) soldiers in Europe was fresh on their minds, as was the Boston Massacre—the deadly culmination of protests by Massachusetts colonists who were frustrated with their obligation to quarter and provide for British troops.

Canva

Amendment IV: Search and seizure

Year ratified: 1791

The framers of the Constitution could not have imagined smartphones, cloud storage, SUV glove compartments, or even organized police forces. Yet the Fourth Amendment they crafted, which protects citizens against unreasonable search and seizure, has been interpreted and applied to all those developments in modern history and many more over the past decades and centuries.

Delanie Stafford // U.S. Air Force Photo

Amendment V: Grand jury, double jeopardy, self-incrimination, and due process

Year ratified: 1791

While watching a courtroom drama unfold on TV, you’ve probably heard a reluctant witness “take the Fifth.” That’s a reference to the Fifth Amendment, which guarantees the right to refuse self-incrimination, as well as other basic protections, including exclusion from double jeopardy and the guarantee that people will not be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process.

Jason Risner Photography // Wikicommons

Amendment VI: Right to a speedy trial by jury, witnesses, counsel

Year ratified: 1791

The Sixth Amendment contains many protections that lay the groundwork for the American criminal justice system and the rights it guarantees to the accused. Among them are the right to be informed of the charges against them, the right to confront accusers, the right to call witnesses, the right to legal counsel, and the right to a speedy, public trial before an impartial jury.

On May 23, 2022, the Supreme Court decided that a federal court cannot consider new evidence outside of the state-court record in deciding whether the state violated an individual’s right to effective assistance of counsel at trial under the Sixth Amendment. The decision, handed down by a 6-3 majority and written by Justice Clarence Thomas, concerned two cases in which people were sentenced to death despite receiving constitutionally ineffective counsel during their respective trials.

The ruling does not revert the protections provided by the Sixth Amendment; however, it weakens them, as individuals who received inadequate counsel in trial and/or post-trial conviction proceedings no longer have recourse to appeal their verdicts to a federal court on that basis. In its dissent, the court’s minority stated its belief that, as a result of the ruling, “the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee is now an empty one.”

Airman 1st Class William Johnson // U.S> Air Force Photo `

Amendment VII: Jury trial in civil lawsuits

Year ratified: 1791

The Seventh Amendment is one of the oddest and most loosely enforced entries in the Bill of Rights. Not only does it specify the seemingly arbitrary benchmark of $20, but it also makes the United States one of the few remaining countries to require that civil trials be conducted by jury, even though less than 1% of such trials are actually decided in this manner.

maveric2003 // Flickr

Amendment VIII: Excess bail or fines, cruel and unusual punishment

Year ratified: 1791

The framers of the Constitution included the Eighth Amendment to ensure that American courts would not institute the extreme forms of torture associated with the Spanish Inquisition and other primitive justice systems suffered by their European ancestors; however, it is one of the most controversial and contentious elements of the entire Bill of Rights, as “cruel” and “unusual” are both subjective concepts.

Canva

Amendment IX: Non-enumerated rights

Year ratified: 1791

The Ninth Amendment is one of the most ferociously contested of all the amendments in the Bill of Rights, and its legal effects are still widely disputed. Like the 10th Amendment, it deals with popular sovereignty and seeks to ensure that citizens do not surrender any rights that aren’t specifically guaranteed in the Bill of Rights.

Lawrence Jackson // Official White House Photo

Amendment X: Rights reserved to states or people

Year ratified: 1791

Like the Ninth Amendment, the 10th (and final) Amendment in the Bill of Rights reiterates the theme of popular sovereignty in the American form of government. The decision of whether or not to include a Bill of Rights in the Constitution was hotly contested by its framers, some of whom were worried about the infringement of rights that weren’t expressly guaranteed.

Loren // Wikicommons

Amendment XI: Suits against a state

Year ratified: 1795

The 11th Amendment prohibits federal courts from hearing specific lawsuits brought against states by citizens from other states or foreign countries.

Canva

Amendment XII: Election of president and vice president

Year ratified: 1804

The 12th Amendment was written in response to the peculiar and massively consequential election of 1800, which represented the first time in history that an incumbent, John Adams, was defeated. That defeat resulted in an Electoral College tie between Aaron Burr and Adams’ vice president, Thomas Jefferson. A congressional vote eventually broke the tie, but the fiasco revealed major flaws in the way presidents and vice presidents were elected under the original Constitution.

Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation — Jeff Kubina // Wikicommons

Amendment XIII: Abolition of slavery

Year ratified: 1865

The 13th Amendment outlawed slavery—with one gaping loophole: “except as a punishment for crime.” When Reconstruction ended, every Southern state installed the brutal system known as convict leasing. For decades following emancipation, hundreds of thousands of Black Americans who had committed no real crime were kidnapped off the streets by corrupt sheriffs. They were hustled through corrupt local court systems, convicted of vague crimes like vagrancy, issued fines they couldn’t pay, and forced to work off those fines building railroads, mining coal, and picking cotton under conditions that were often worse than those endured by people enslaved prior to the 13th Amendment’s ratification.

Karen Neoh // Flickr

Amendment XIV: Privileges and immunities, due process, equal protection, apportionment of representatives, civil war disqualification, and debt

Year ratified: 1868

One of three amendments designed to protect Black Americans in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the 14th Amendment guaranteed equal protection under the law without regard to race. Like the 13th and 15th Amendments, it created dramatic change during Reconstruction, but Black citizens were quickly denied its protections when Reconstruction ended. Millions of newly freed enslaved persons were left to the mercy of their defeated and enraged former masters, who reclaimed control of local and state governments.

Yoichi Okamoto // Wikicommons

Amendment XV: Right to vote not to be denied on account of race

Year ratified: 1870

The 15th Amendment gave Black men the right to vote though that right was largely symbolic until major civil rights legislation was signed in the mid-1960s—nearly a century after the Reconstruction era . When Reconstruction ended, white supremacist governments once again took over the South as well as many other areas of the country. They used mechanisms ranging from poll taxes and literacy tests to acts of violence and terrorism to keep Black people as disenfranchised as possible.

PxHere

Amendment XVI: Income tax

Year ratified: 1913

The 16th Amendment was part of a wave of early 20th-century reforms that changed the relationship between the federal government and the citizens of the United States. The enabling of a nationwide income tax played a key role in the rise of the modern, powerful federal government, which would quickly come to rely on income tax as its chief source of revenue.

Brady-Handy Photograph Collection // Wikicommons

Amendment XVII: Popular election of senators

Year ratified: 1913

It’s been more than a century since the 17th Amendment empowered the people to directly elect the senators who represent their states. It’s hard to imagine what Congress would look like today if senators were still chosen by state legislatures, as they were prior to 1913.

Orange County Archives // Wikicommons

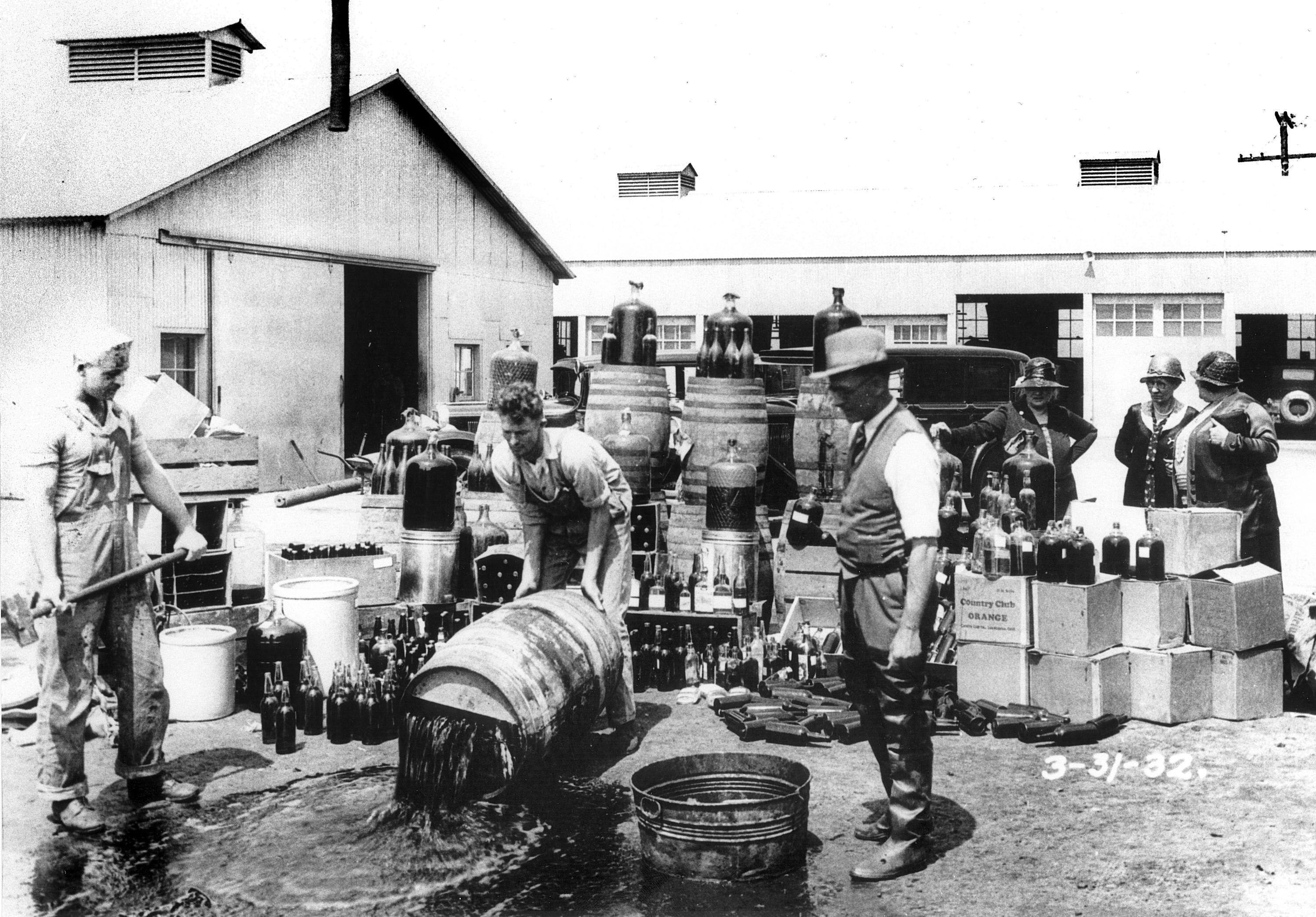

Amendment XVIII: Prohibition

Year ratified: 1919

More than a half-century before Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” America established the 18th Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors. But in reality, Prohibition did none of that. Americans kept drinking—and similar to the illegal drug trade, the act created a black market that fueled an unprecedented rise in violent crime and urban warfare as organized gangs battled for control of the lucrative underground trade.

Canva

Amendment XIX: Women’s right to vote

Year ratified: 1920

Representing a watershed moment for equality and freedom in American history, the 19th Amendment was the crowning achievement of a nearly century-long active struggle for women’s rights. The codification of women’s suffrage with the ratification of the 19th Amendment was built on the shoulders of giants like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott, whose relentless protests changed the consciousness of the American patriarchy.

Canva

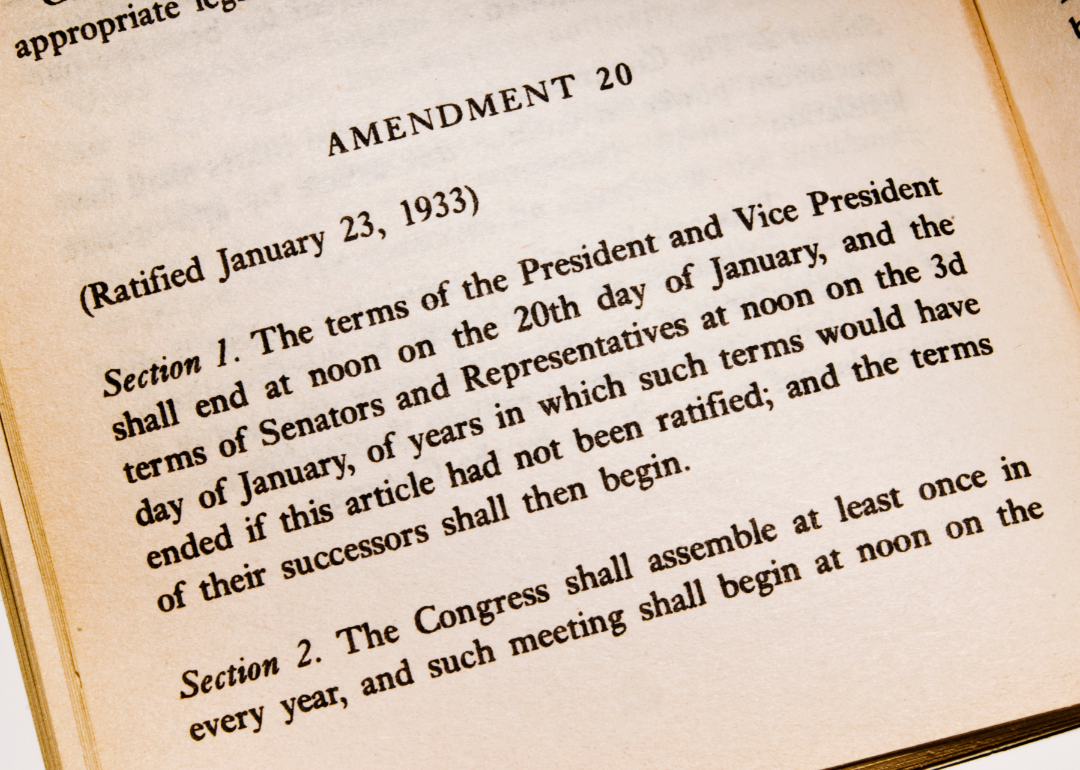

Amendment XX: Presidential term and succession

Year ratified: 1933

Few amendments have been passed with less fanfare, controversy, and discussion than the 20th Amendment, which modifies part of the Constitution and the 12th Amendment, mostly to clarify start dates for terms of office. To this day, it has never been the subject of a Supreme Court decision.

H. Michael Miley // Flickr

Amendment XXI: Repeal of prohibition

Year ratified: 1933

Fourteen years after the 18th Amendment made Prohibition the law of the land, the 21st Amendment repealed it. It remains the only time in American history that the Constitution was amended to overturn a previous amendment.

George Trian // Wikicommons

Amendment XXII: Two-term limit on presidency

Year ratified: 1951

Few issues puzzled the framers of the Constitution more thoroughly than the process of choosing a president and determining the length of time for which a president should serve. After all, European monarchies offered no precedent on which to base the new executive office. While many framers wanted the presidency to be a lifetime appointment, President George Washington’s decision to retire after his second term set the tone for a voluntary two-term limit. This lasted for 150 years, but the dual crises of the Great Depression and World War II led Americans to elect Franklin D. Roosevelt to four terms in office, stoking fears of future tyranny that led to the ratification of the 22nd Amendment.

Autopilot // Wikicommons

Amendment XXIII: Presidential vote for DC

Year ratified: 1961

Washington D.C. has been the seat of government in the United States for nearly as long as America has been a country, but residents of the District of Columbia have only been allowed to vote in presidential elections since 1961. The 23rd Amendment granted that right. As a city with a Black majority, newly acquired votes added even more steam to the escalating civil rights movement. In turn, the measure encountered fierce resistance in the South.

Cecil W. Stoughton // Wikicommons

Amendment XXIV: Abolition of poll taxes

Year ratified: 1964

The 24th Amendment prohibits the use of the poll tax, a mechanism Southern states used to enforce white supremacy and disenfranchise Black Americans for nearly a century following the Civil War and Reconstruction. With poverty rampant among Black and white Southerners, few could afford to pay to exercise their right to vote. Grandfather clauses, however, often exempted anyone whose ancestors voted before the Civil War, which allowed many poor whites to vote for free while excluding virtually all Black Americans living in former slave states.

Cecil W. Stoughton // Wikicommons

Amendment XXV: Presidential disability and succession

Year ratified: 1967

The issue of presidential succession was addressed in Article 2, Section 1, Clause 6 of the original Constitution. But flaws in the document’s vague and convoluted wording were exposed in 1841 when President William Henry Harrison died, leaving Vice President John Tyler to fight for his claim to the presidency. One of the more complex amendments, the 25th Amendment, clarifies the issues of presidential succession in four sections.

Vox Efx // Flickr

Amendment XXVI: Right to vote at age 18

Year ratified: 1971

The 26th Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. Debates over the hotly contested amendment started during World War II and came to a head during the Vietnam War. The country was collectively outraged that 18-year-old men could be drafted for involuntary military service and foreign combat right out of high school but were still three years away from being old enough to vote for their own leaders.

Lawrence Jackson // Wikicommons

Amendment XXVII: Compensation of members of Congress

Year ratified: 1992

The 27th Amendment seems fairly straightforward, maintaining that members of Congress may not alter their salaries midterm. But the so-called compensation amendment’s bizarre centuries-old saga from its original proposal to ratification was a meandering journey. It started during the first session of Congress in 1789 and didn’t end until the dawn of the digital age. No other amendment languished in limbo for a longer period of time.