A timeline of the Civil War

Published 3:30 pm Monday, July 17, 2023

A timeline of the Civil War

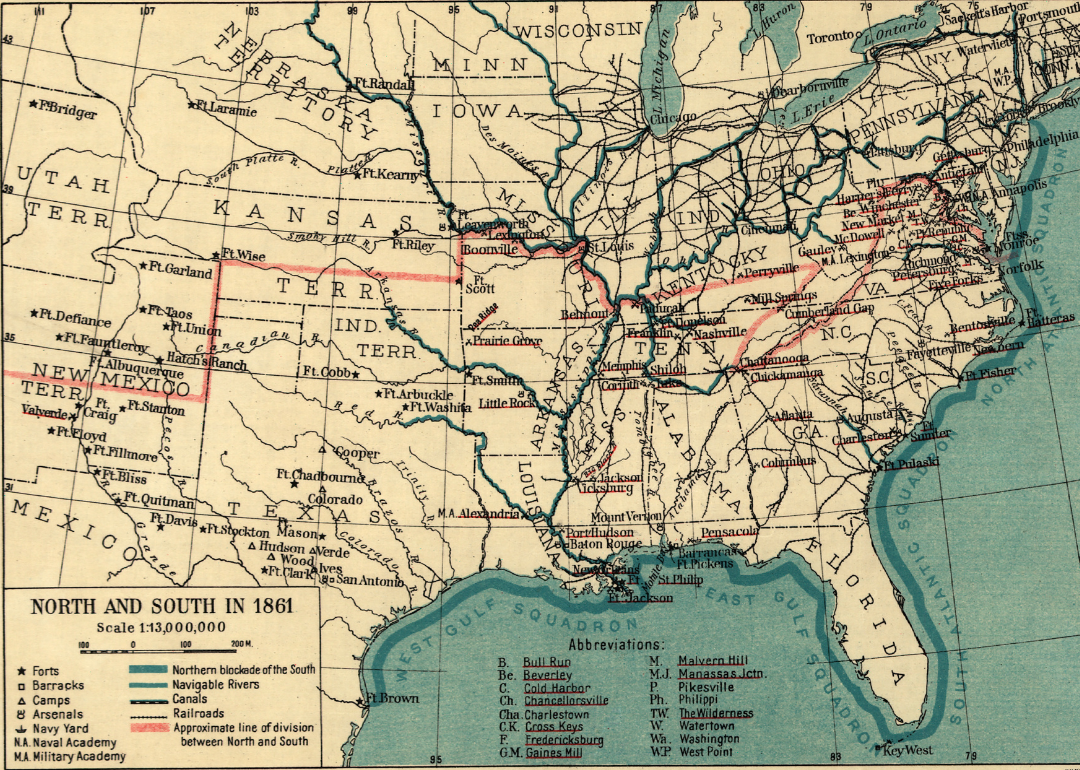

Throughout the early 1860s, the Northern and Southern states held sustained disagreements on several key issues, including economic policies, cultural values, the power and reach of the federal government, and slavery. The latter issue was of paramount concern for the Southern states, whose economy was highly dependent on agriculture, unlike the more industrialized states of the North.

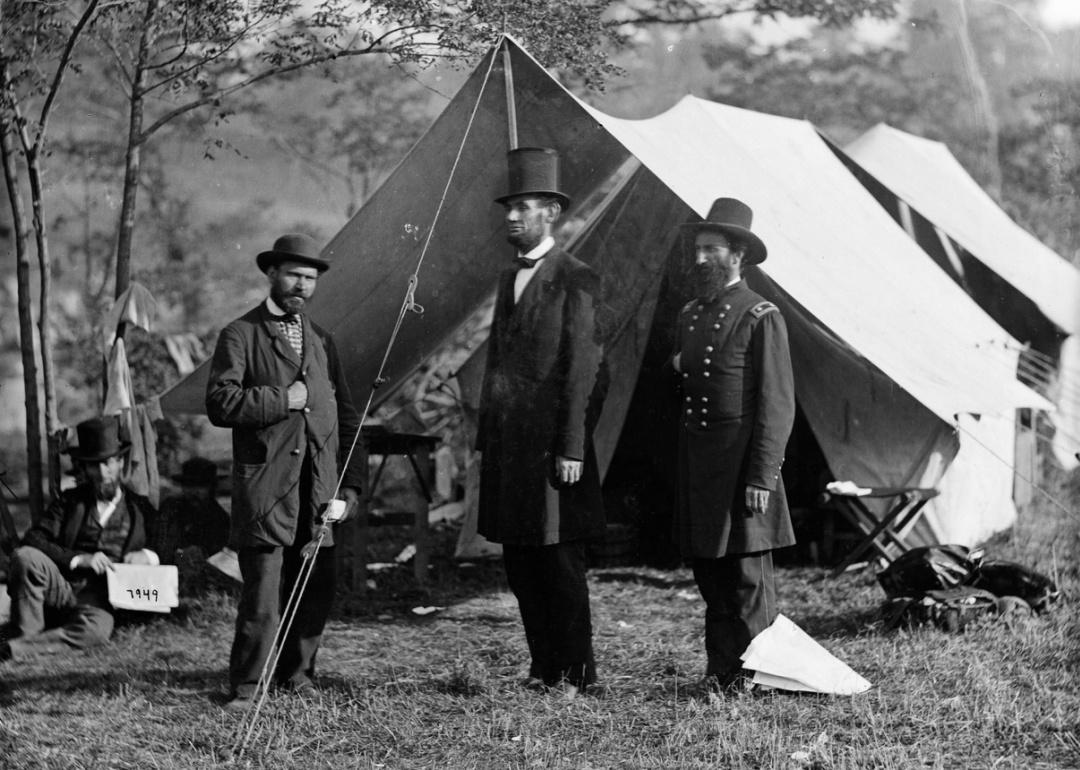

A fracture point was reached in 1860 when Abraham Lincoln, an opponent of slavery, was elected to the presidency, spurring several state legislatures to openly debate an act of secession from the United States. The first to do so was South Carolina, which summoned a state convention in December 1860, shortly before Lincoln officially took office, where delegates voted to leave the Union. In short order, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas would follow.

In February 1861, representatives of these seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama, to draft the Confederate Constitution. Similar to the U.S. Constitution, the Confederate Constitution granted each state broader autonomy and made the practice of slavery a protected system. The delegates chose Jefferson Davis as provisional president of the newly formed Confederacy. The Constitution of Confederal States was officially adopted on March 11, 1861.

Federal forts in the seceding states were overtaken by Confederate troops when Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan Jr., refused to cede the garrisons to the South. Troops loyal to the Confederacy repulsed a ship back to New York when it tried to deliver supplies at Fort Sumter, South Carolina.

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln’s inauguration took place. Despite being known as an abolitionist, in his speech, Lincoln stated he had no plans to end slavery where it already existed. He also affirmed that he would not accept secession from any state and wished to resolve the crisis that began after his electoral victory without warfare. His hopes lasted a little over a month before, on April 12, the nation was thrust into one of the bloodiest military conflicts in U.S. history.

More than 150 years later, the Civil War continues to fascinate readers with a taste for historic minutiae. Stacker compiled a timeline of the war using various historical and academic sources.

![]()

VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

Gunfire at Fort Sumter

On April 11, 1861, President Lincoln alerted South Carolina Gov. Francis Pickens of his plans to send supplies to the garrison at Fort Sumter rather than prepare for its evacuation. Consequently, Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard demanded that Robert Anderson—the U.S. Army commander of the post—surrender.

Anderson offered to do so only after exhausting his supplies. Wanting the fort emptied before a resupply could reach it, the Confederacy opened fire in the early hours of April 12. On April 14, the siege ended with the fort’s evacuation.

The Civil War had begun.

DEA / BIBLIOTECA AMBROSIANA // Getty Images

Lincoln calls in troops to contain the insurrection

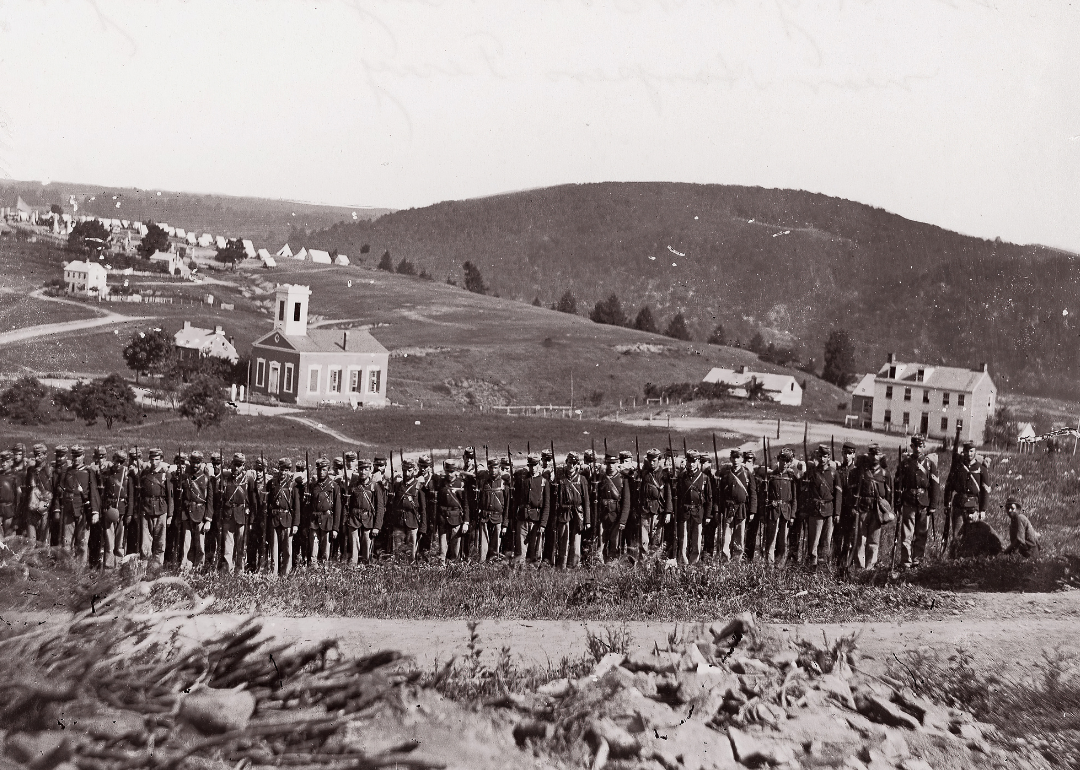

Three days after the official beginning of the war, President Lincoln issued a public declaration informing the American people an insurrection had taken place in the South. He called forth the state militias—some 75,000 troops—to contain the rebellion.

History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Four more states join the Confederacy

The attack on Fort Sumter incited Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee to join the Confederacy. Richmond, Virginia, was designated the seat of government of the Confederate States of America.

Buyenlarge // Getty Images

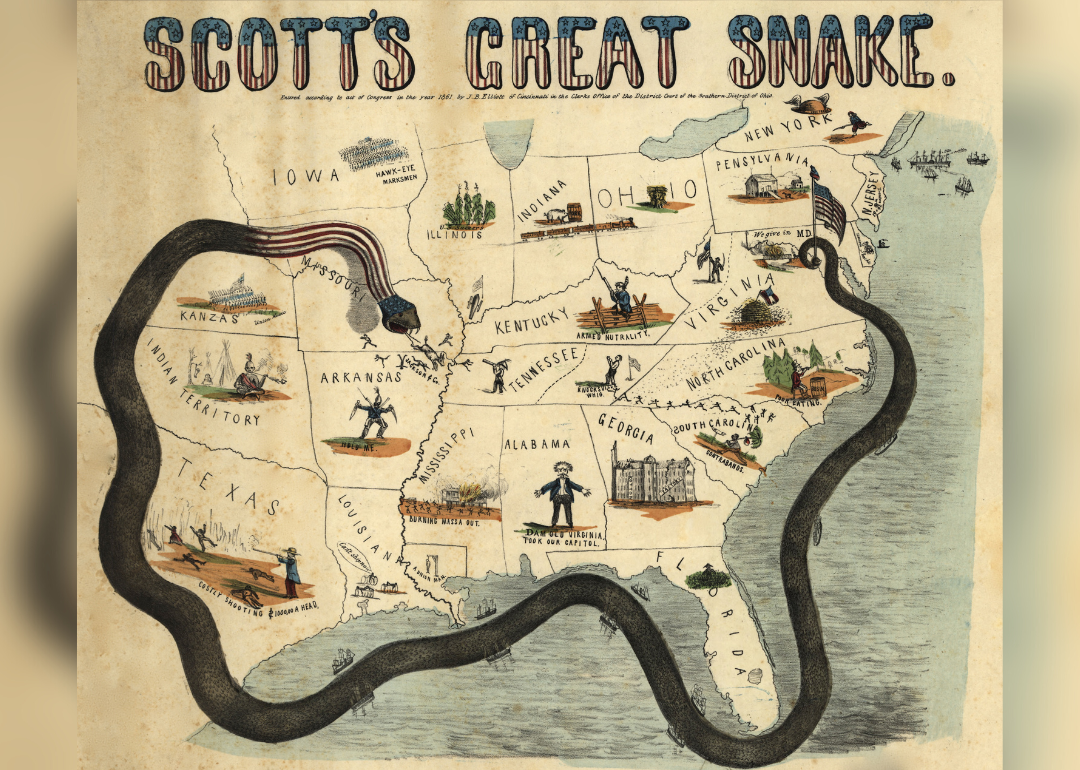

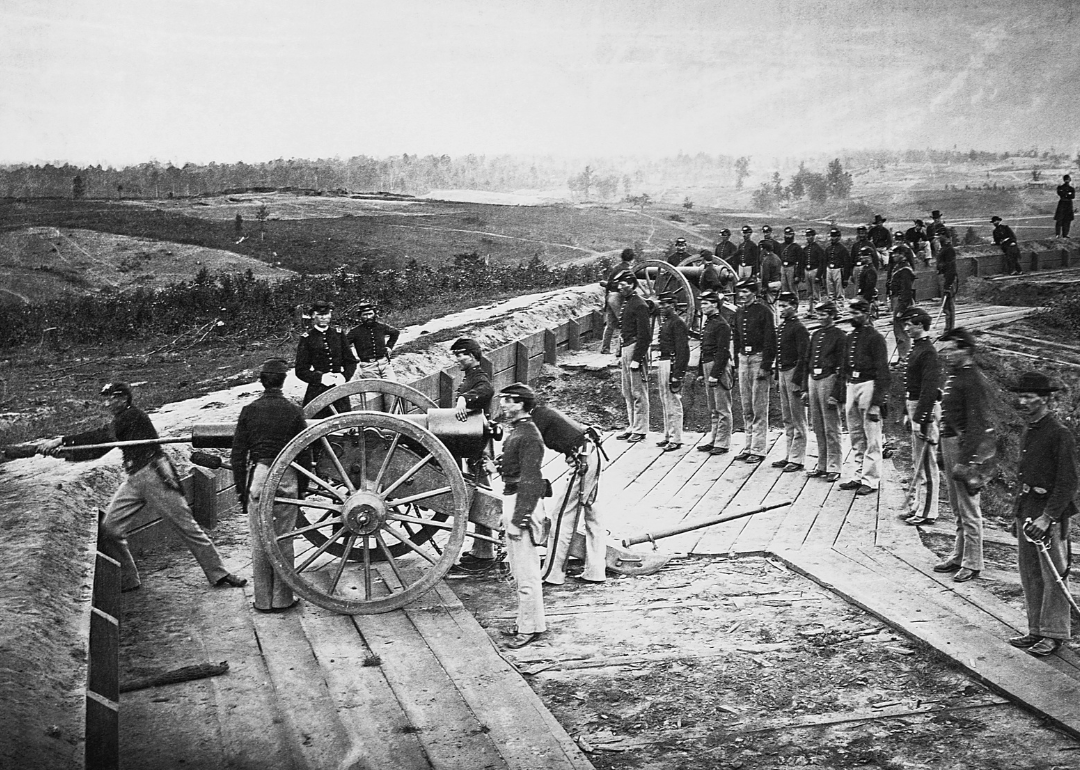

Blockade of Southern ports

In a move still considered bold, overambitious, and risky, Lincoln ordered the blockade of all seaports in the South on April 19, 1861. At the time, it was the first measure of marine warfare and the largest obstruction ever attempted worldwide. The Union’s Navy only had three steam vessels available to undertake the task. Nonetheless, the measure was sustained for four years.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Birth of West Virginia

After months of debate between state authorities, Virginians agreed to leave the Union in April 1861. However, the western counties of the state still needed to conform. While the state remained politically divided through the war’s first two years, the U.S. finally admitted the nonadherent portion into the Union in June 1863 as the state of West Virginia.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The ‘Border States’ refuse the Confederacy but not slavery

Delaware, Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland refused to join the Confederacy—or perhaps, more accurately, were precluded from doing so thanks to various political stratagems and military coercion on the part of the Union. Consequently, these “Border States” became a persistent worry for President Lincoln, who feared he would eventually lose them to the South by dint of their continued engagement with the industry of slavery.

Bettmann // Getty Images

The First Battle of Bull Run

After several engagements at different points of Missouri and Virginia, the war’s first major battle occurred on July 21, 1861, in Manassas Junction, Virginia, also called Bull Run. Union Gen. Irvin McDowell successfully advanced on Confederate troops, but the addition of Southern reinforcements marked the first victory for the Confederacy. Federal troops were forced to retreat to Washington.

Culture Club // Getty Images

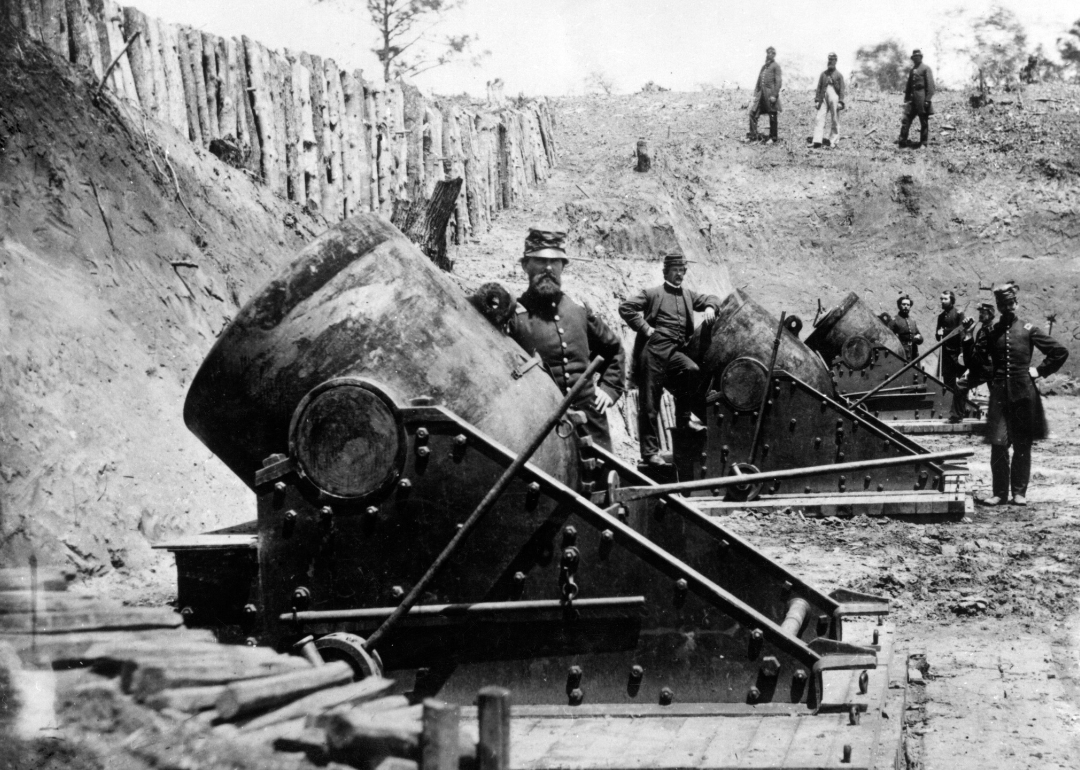

The Battle of Fort Royal

Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard were seized on Nov. 7, 1861, in a successful amphibious operation by the Union Army and Navy. The victories enabled Gen. Thomas Sherman’s troops to take hold of Port Royal and the Sea Islands of South Carolina.

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY / Contributor // Getty Images

The Battle of Shiloh

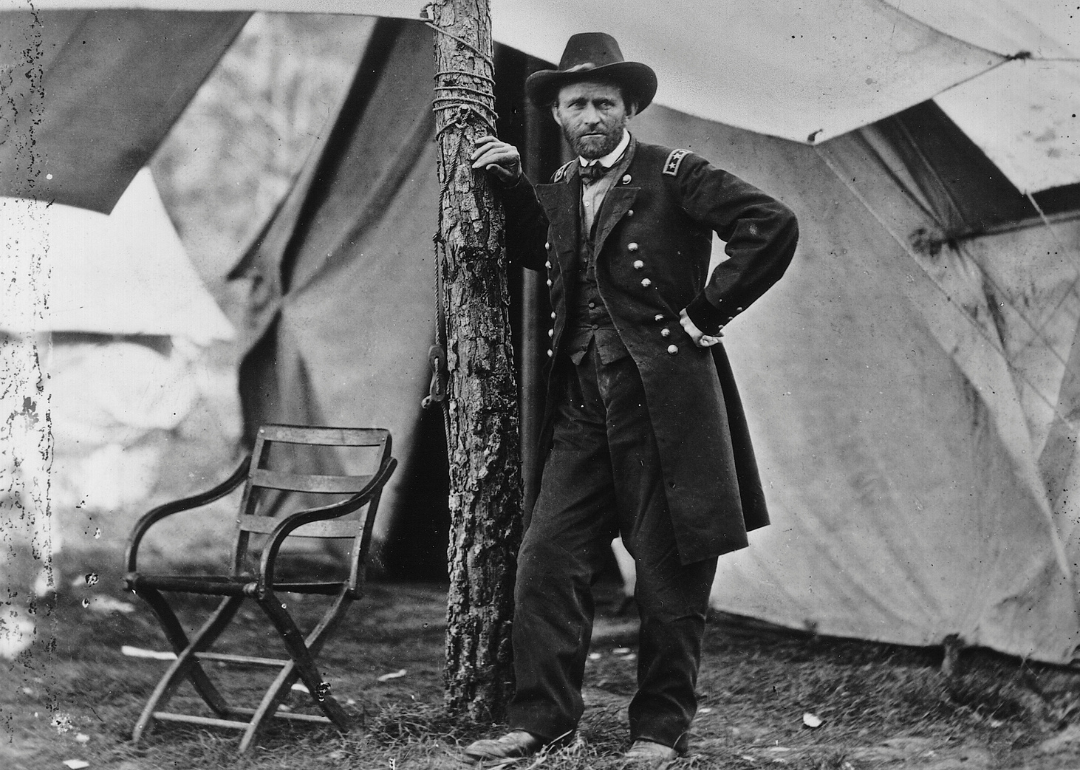

More than 100,000 troops fought at Shiloh between April 6-7, 1862, and some 23,000 either died or were wounded. Ulysses S. Grant led Union forces to a victory that would lay the ground for an even larger campaign along the Mississippi River Valley, culminating in the Vicksburg Campaign, which raged on until July 1863.

Mondadori via Getty Images

The Peninsula Campaign

The Union’s Army of the Potomac, under the command of Gen. George McClellan—appointed general-in-chief of all U.S. forces in November 1861—was ordered to attack Richmond in the spring of 1862. The move prompted the Peninsula Campaign, an operation that transpired in the Virginia Peninsula, a strategic entry to the Confederacy’s capital.

After several Federal attacks by land and water, including the battles of Williamsburg and Drewry’s Bluff, the Confederates withdrew progressively to Richmond while Union troops reached the city’s outskirts. One of the roughest engagements followed: the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, which exposed an outnumbered Union army. Confederate Cmdr. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston was wounded in Seven Pines and replaced by Gen. Robert E. Lee in June 1862.

Bettmann // Getty Images

The Seven Days Battles

From June 26 to July 2, 1862, several battles transpired at various sites in Virginia: Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, Savage’s Station, Frayser’s Farm, and Malvern Hill. Newly installed Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army sustained massive losses, but the fighting ultimately resulted in the Confederacy’s primary goal: saving the city of Richmond.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

From the Second Battle of Bull Run to the Battle of Fredericksburg

During the second half of 1862, several bloody conflicts left both armies mourning thousands of casualties. The Union lost the Second Battle of Bull Run on Aug. 30 and struggled to recover. The deadliest day of the war up to that date was on Sept. 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, where 12,401 Union soldiers and 10,316 Confederates died and thousands were injured. That confrontation ended with no winner, but the Union was defeated months later by Confederate forces at Fredericksburg, Virginia, where the North sustained nearly equal loss of life.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln presented an outline of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet on July 22, 1862, followed by a full preliminary version on Sept. 22, stating that unless the Confederate rebellion ceased by Jan. 1 of the following year, the proclamation would take full effect.

One-hundred days later, the Confederacy remained intact, and the proclamation officially granted freedom to all enslaved people in all U.S. states, including those within the Confederacy. It also allowed Black men to serve in the Union Army. Until then, the Confederacy expected the English and French governments to intervene in its favor. Still, Lincoln’s shift to make the war a fight against slavery made international intervention distinctly unpalatable.

DEA / BIBLIOTECA AMBROSIANA // Getty Images

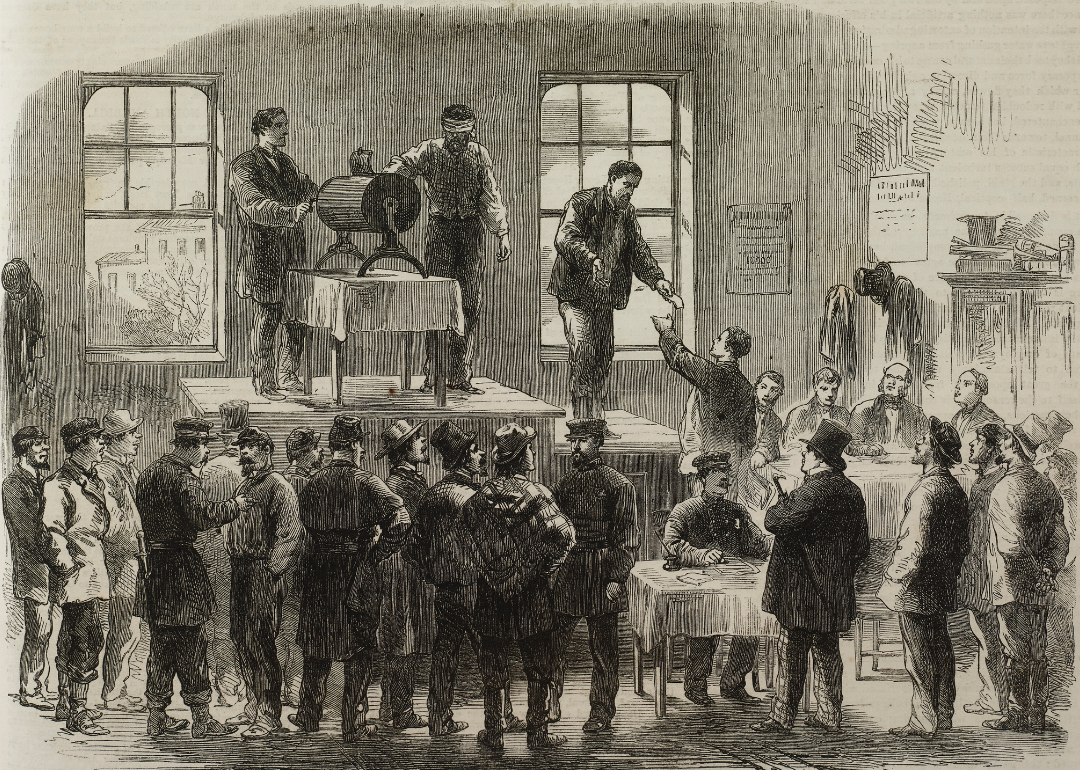

The Conscription Act of 1863 establishes a national draft

All nondisabled men between the ages of 20 and 45, citizen and immigrant alike, were conscripted to the Union Army by the Conscription Act of 1863. The act was considered unfair to people experiencing poverty, as service could be eluded by paying a fee or finding a volunteer substitute to take one’s place. Violent protest riots erupted in New York City in July 1863, leaving at least 120 people dead (some accounts report a death toll of as many as 1,000). A parallel conscription act was approved in the Confederacy, prompting a similar uproar.

Stock Montage // Getty Images

The Battle of Gettysburg

In late June 1862, Confederate forces, trying to gain positions in the North, crossed the Potomac en route to the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. Gen. Robert E. Lee, while awaiting an intelligence report, is informed by a covert agent within Union forces that Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s forces are gaining ground, spurring Lee to send his troops to Gettysburg.

The resulting three-day battle was a turning point for the North and the bloodiest confrontation of the war. Estimated casualties were a combined 50,000 from both armies. The Union—with more soldiers and strategic positions—won the fight but could not follow the defeated Confederates back to Virginia. Lincoln later turned a portion of the Gettysburg battlefield into a national cemetery, where he later delivered his memorable Gettysburg Address.

Universal History Archive // Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The Confederacy splits in two

After several costly losses to the South near the Rappahannock River, the Union regained control of Vicksburg in July 1863. After six weeks of combat, the Confederates surrendered the city after losing nearly all 33,000 troops. Soon after, the North captured Port Hudson, Louisiana, splitting the Confederacy.

Buyenlarge // Getty Images

Union victories in Tennessee

On Sept. 19, 1863, both sides fought along the Tennessee-Georgia border. The Confederacy controlled the area, forcing the Union to retreat to Chattanooga. A few weeks later, Union troops drove Confederate forces away from Chattanooga through an effective series of attacks commanded by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. In retaliation, the Confederates tried pushing Union troops out of eastern Tennessee; however, Union soldiers managed to retreat and defend Fort Sanders in Knoxville, losing five soldiers to the Confederates’ 813. The series of victories in Tennessee set the stage for Gen. William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign.

Encyclopaedia Britannica/UIG Via Getty Images

Grant’s Wilderness Campaign

By the spring of 1864, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, now commander of all Union armies, was set on nothing less than the capture of Richmond, Virginia, and the total surrender of all Confederate forces. Though it lacked a conclusive victor, the three-day Battle in the Wilderness was a crucial first step in Grant’s push toward Richmond. Grant counted more casualties than Lee, but unlike the South, the North had readily available replacements, allowing Grant to continue attacking Lee’s positions. A skirmish at the Spotsylvania Court House in May resulted in 30,000 casualties from both sides and was also deemed inconclusive, even though both parties declared victory.

Grant’s men attacked Confederate forces again in June 1864 at Cold Harbor. The Union lost about 7,000 men in 20 minutes. Lee suffered fewer casualties, but his army could never recover from Grant’s back-to-back attacks. This was the Confederacy’s last clear victory under Lee’s command.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The capture of Atlanta

Union Gen. William T. Sherman captured the city of Atlanta on Sept. 2, 1864. His “March to the Sea” strategy meant destroying everything he encountered on his march through Georgia and the Carolinas to interrupt the Confederate troops’ supply chain. His men destroyed every crop, railroad, bridge, and factory they found on their path.

Glasshouse Vintage/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

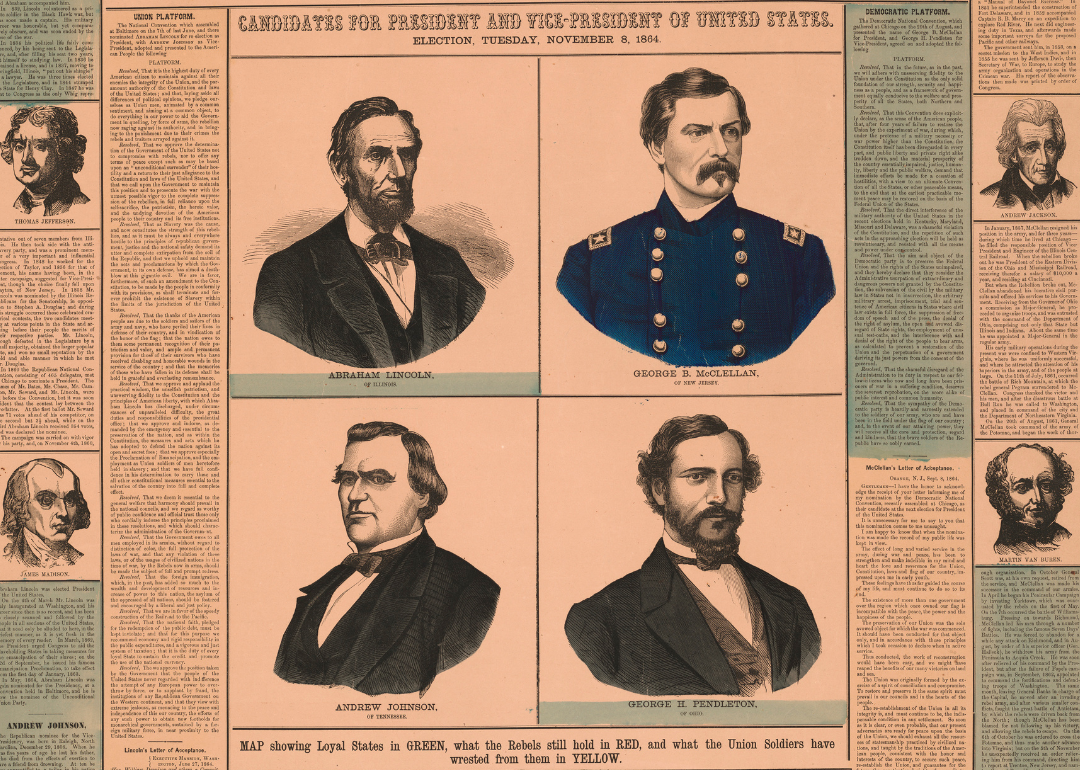

Lincoln is reelected

The siege of Atlanta was a morale boost for the Union—and President Lincoln’s reelection campaign. Before Sherman’s victory in Atlanta, war weariness diminished Lincoln’s chances of winning at the polls. Radical Republicans considered the president too clement with the rebel states when he vetoed the Wade-Davis bill, a law meant to force the majority of voters in the Confederacy to swear loyalty to the Union before the state could be restored. With Andrew Johnson as his vice-presidential candidate, Lincoln won reelection by an ample margin, the first to do so since Andrew Jackson in 1832.

Stock Montage/Stock Montage // Getty Images

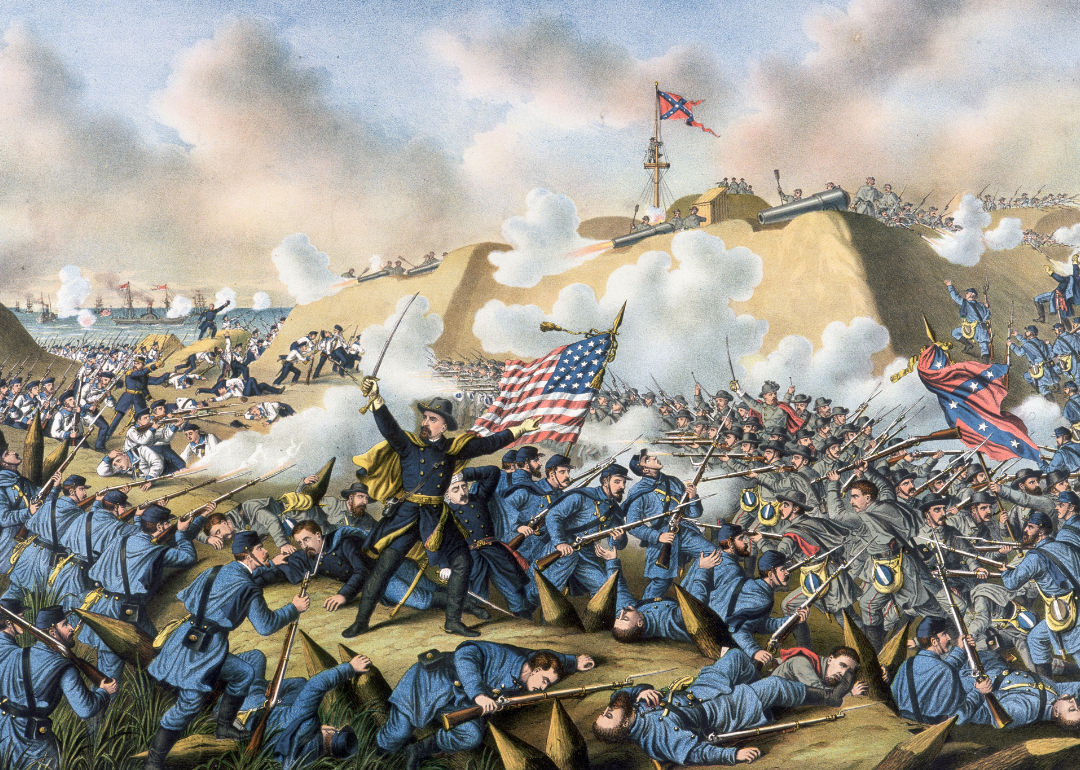

Submittal of the Forts

Gen. William T. Sherman ordered an attack on Fort McAllister, located near Savannah, Georgia, on Dec. 13, 1864. It was strategically necessary to allow Sherman access to much-needed supplies from the Ogeechee River. Tapping Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard and Brig. Gen. William B. Hazen, Sherman’s legions not only took the fort with minimal casualties but also seized the city of Savannah a week later. He immediately ordered his troops north. The following month, a squadron of warships besieged Fort Fisher, North Carolina. Union troops took control of Wilmington, the last stronghold of the Confederacy.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

The Confederacy falls

Transportation and supply blockades caused severe food shortages in the South. Famished troops began leaving Gen. Robert E. Lee’s last positions. In a desperate attempt to replace the deserters, Confederate President Jefferson Davis approved enlisting and arming enslaved people—the measure was never enforced.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

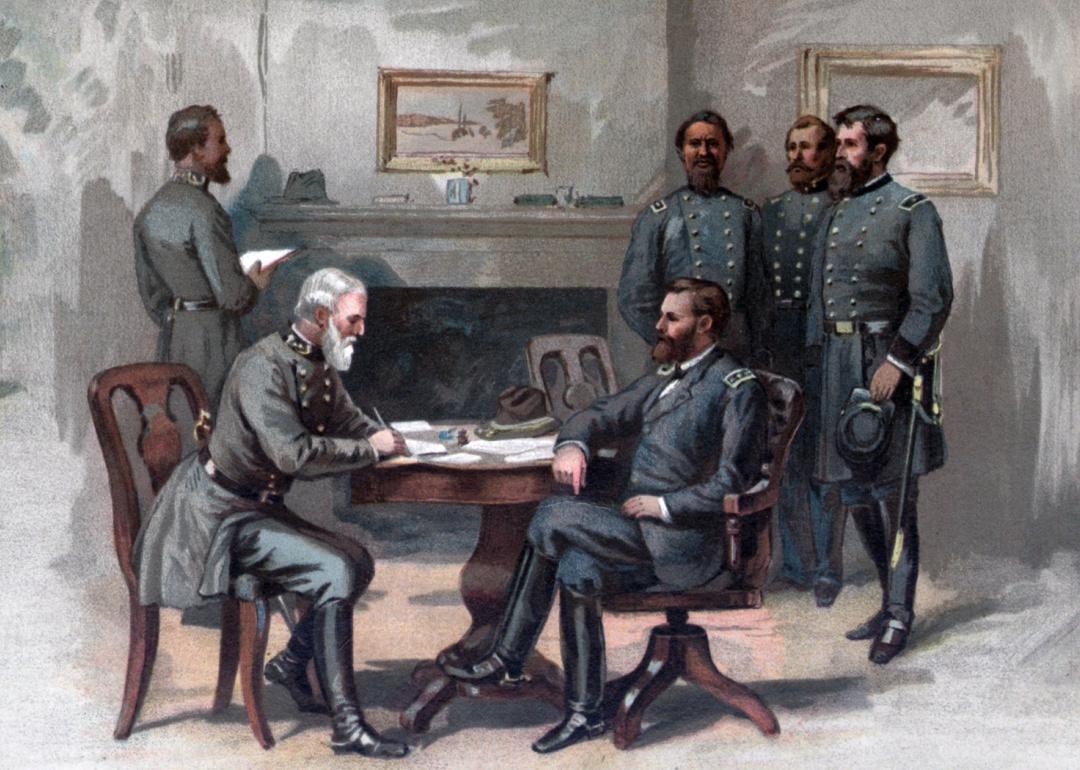

Surrender of the South

Confederate President Jefferson Davis agreed to send delegates to meet with President Lincoln to discuss a peace agreement, but only if the Union first recognized the Confederacy’s independence. Lincoln refused.

On March 25, 1865, Gen. Robert E. Lee began a series of attacks on Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s positions near Petersburg but was defeated every time. Grant demanded Lee’s surrender.

The two commanders met at the Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, to agree on terms of Confederate capitulation. It is considered the official date on which the Civil War ended, though the last battle was fought in Palmito Ranch, Texas, on May 13 (and was, ironically, a Confederate victory). Soldiers were allowed to go home on their horses, and officers could take their sidearms. Everything else was yielded to the Union.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images // Getty Images

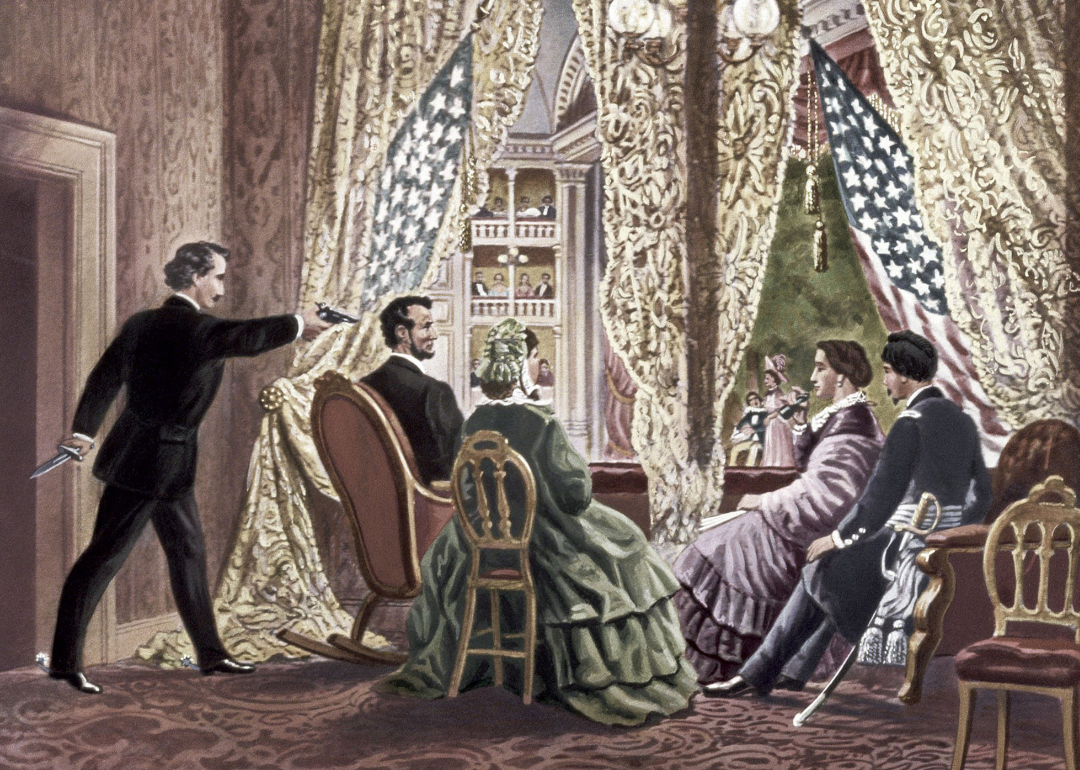

The assassination of President Lincoln

While attending a performance at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C., President Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, a pro-Confederacy actor seeking revenge for the South’s defeat. Initially, Booth escaped but was cornered and shot dead by a Union soldier 11 days later in Virginia. Nine other people involved in the president’s murder were prosecuted—one was acquitted, four hanged, and four incarcerated. Lincoln died at the Petersen boardinghouse shortly after being shot.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Jefferson Davis is finally captured; the last Confederate troops lay down arms

After moving south several times, hoping to reinstate the Confederacy—Ge. Robert E. Lee signed the order of surrender without Jefferson Davis’ direct approval—Davis was arrested in central Georgia on May 10, 1865. After two years under guard, Davis was eventually released on bail in 1867 and moved to Canada. The U.S. government did not pursue charges against him. The county where he was captured now bears his name.

Between April and mid-May 1865, the remaining Southern troops were defeated. The Union armies of the Potomac and Tennessee/Georgia paraded in victory on May 23-24, respectively.

On Nov. 10, 1865, Henry Wirz, commander of the Confederate prison in Georgia, was hanged. He was the only officer of the Confederacy prosecuted for war crimes.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Paris Close.