Teen mental health is in crisis in the US, and schools are ill-equipped to help

Published 9:15 pm Tuesday, April 23, 2024

Teen mental health is in crisis in the US, and schools are ill-equipped to help

American teenagers are growing more anxious, depressed, and lonely—and many have limited or no access to the help and resources they so desperately need.

In 2021, the surgeon general issued a warning about young Americans’ deteriorating well-being in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, pointing out increased feelings of sadness and hopelessness amongst people aged 10 to 24. However, youth mental health was in decline well before the coronavirus upended lives, and the situation has not improved since.

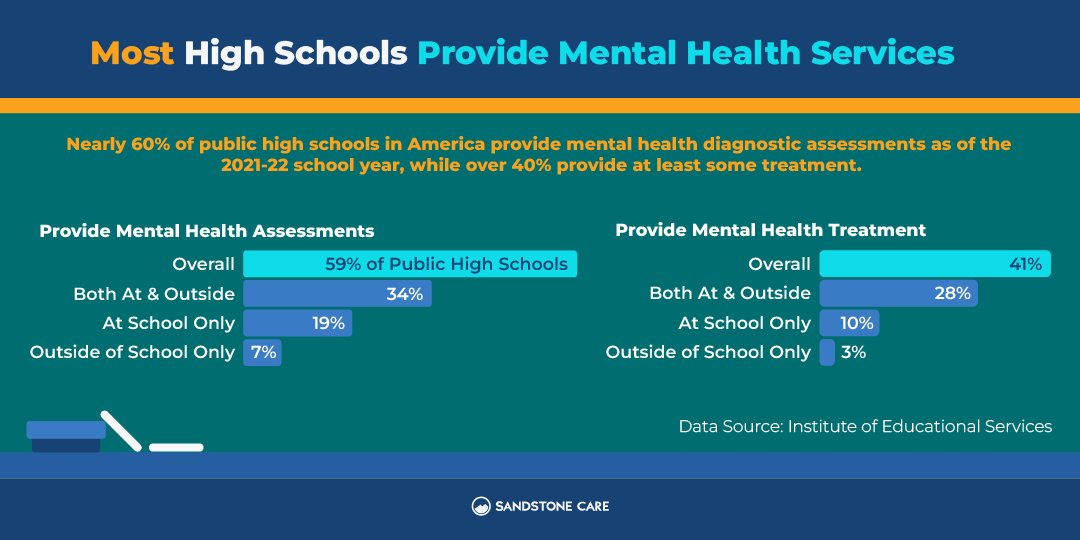

Using data from the Institute of Education Sciences, Sandstone Care explored the prevalence of mental health treatment, assessment, and other services in schools.

Trending

According to a 2023 survey by EdWeek, 93% of health workers at schools reported that, since 2019, they’ve seen more students with anxiety. What’s more, the share of high schoolers who say they consistently feel sad or hopeless rose from 28% in 1999 to over 42% in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control. During this same period, the share of teen girls who reported feeling so sad that they stopped doing some of their usual activities jumped from 36% to 57%.

School settings have long been considered the most accessible location for providing children and teens with behavioral and mental health services. School-based services and screenings help with prevention and early identification, and can provide much-needed services to underserved populations.

Numerous factors are driving the well-documented mental health crisis among America’s youth. Increasingly high academic expectations are part of the problem. The EdWeek survey found that 34% of high school-aged students reported schoolwork-related stress negatively impacted their mental health, while 28% pointed to worries about grades and test scores.

A study published in the February 2024 edition of Economics of Education Review points to activity overload as another culprit. Fuelled in part by the college admissions arms race, students spend increasingly more time on enrichment activities at the cost of sleep and socialization. Researchers found that the last hour of extracurriculars, such as music and art lessons, has zero effect on cognitive skills and significantly negatively impacts noncognitive skills, such as emotional well-being and social interactions.

In other words, teenagers are becoming more stressed and not necessarily better at the activities meant to give them a competitive edge.

In recent years, researchers have pointed to the proliferation of social media as a significant reason for teenagers’ declining mental health. The matter made headlines in May 2023 with the surgeon general’s warning regarding the mounting evidence about social media’s adverse effects on adolescent well-being. Concerns about physical appearances and anxiety about society also contribute to the uptick in anxiety and depression, among other factors.

Trending

The facts are clear: Teenagers today sleep less, spend less time with friends, and report more feelings of loneliness. For some students, ongoing mental health issues are a matter of life and death: Over 1 in 5 high school students have seriously considered suicide, according to CDC data, with students identifying as LGBQ+ three times more likely than their peers to report contemplating suicide.

The mental health crisis is worsening—and policymakers and mental health professionals have taken notice. To address this drastic decline in student well-being, recent policy initiatives to expand mental health services in schools and increase accessibility to teens are on the table.

Despite these promising initiatives, mental health services in schools are strained.

![]()

Illustration by Joel Daniel // Sandstone Care

Schools are increasing efforts to offer much-needed mental health services

IES data shows around 59% of public high schools in America provided mental health assessment services, while 41% provided treatment during the 2021-22 school year.

Services included outreach, individual counseling, and referrals to external mental health care providers. Some schools have adopted multi-tiered systems that provide different levels of support, such as universal lessons on mental health awareness and more targeted, intensive services for students in need.

In general, schools with a large student body are more likely to be able to diagnose mental health disorders, with 63% of schools with at least 1,000 students conducting health care assessments, compared with just 39% of schools with fewer than 300 students. Similarly, schools in cities and suburbs were much more likely to diagnose mental health disorders than those in rural areas, according to the IES report.

All told, only about half of K-12 public schools report they can effectively provide mental health services for all students in need. Roughly two-thirds of public schools that offer mental health services have on-site licensed mental health professionals, while around half rely on external professionals.

Staffing shortages limit services

Even schools that do employ mental health workers are often understaffed. During the 2022-23 year, American public schools averaged just one counselor for every 385 students. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250-to-1. Moreover, many American students who need mental health support are not getting any at all.

Various factors contribute to staffing shortages or limit the extent of services offered, with 73% of schools citing the lack of access to licensed mental health professionals and 69% blaming a lack of funding. Many schools rely on teachers, who may be the first to observe mental health problems in their students, as the first line of defense. Although they may spot issues and track student progress, they often lack the training to identify adolescents in need.

To help address the ongoing mental health crisis, the Department of Education announced in February 2024 a new program that would increase the number of mental health professionals in schools, allocating $38 million toward the goal. This funding would bolster local and state initiatives, such as Boston’s recent $21 million plan to improve youth mental health or New York state’s $5.1 million plan to establish school-based mental health clinics.

The pandemic was not the only reason for teenagers’ declining well-being. Yet, it did put the youth mental health crisis on the radar of both policymakers and the general public. There’s a long road up ahead, but bringing the crisis out of the shadows and normalizing conversations about teen mental health is a positive first step.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Sandstone Care and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.