How the racial wage gap has fallen—and risen—over the past two decades

Published 6:00 pm Thursday, May 2, 2024

How the racial wage gap has fallen—and risen—over the past two decades

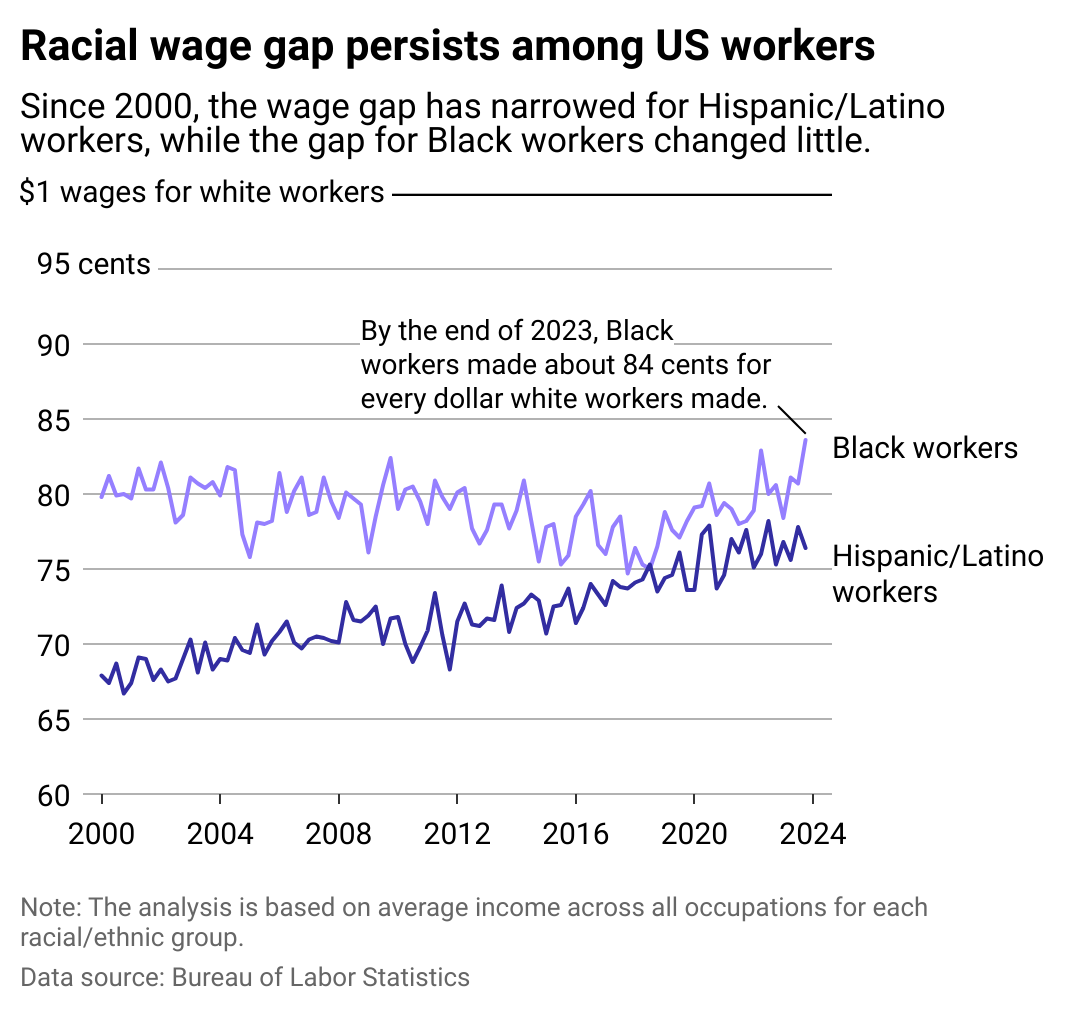

For every dollar a typical white worker earns in America, a Black worker earns 84 cents, and a Hispanic or Latino worker earns just 76 cents. The racial wage gap is persistent, and as policy and the economy change, so do the disparities.

Differences in education and experience—which are often used to explain away the pay gap—explain less than half of the disparity in compensation between Black and white workers, according to a 2022 Economic Policy Institute study. Data points to structural racism and discrimination in hiring, pay, and promotions as likely causes for Black workers remaining underpaid and underemployed.

Black and Hispanic households in the U.S. have far less wealth compared to their white counterparts, according to a 2023 Pew analysis. Their children, in turn, may have fewer opportunities to acquire high-paying jobs and build wealth. As a result, racial pay gaps appear even among the youngest workers in the economy, and it can be difficult—or impossible—for their wages to catch up.

Xactly charted how the racial wage gap has changed since 2000 using the Bureau of Labor Statistics data. BLS, the data source used here, asks survey respondents who identify as Hispanic or Latino to specify their country of origin. This story compares Hispanic and Latino workers to non-Hispanic Black and white workers as a way to highlight the inequalities those from Hispanic or Latino backgrounds face in the U.S. economy.

Editor’s note: It is essential to understand that race and ethnicity are two different demographic measureS. People of any race can have Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. The categorization of Hispanic and Latino workers into one group is not to ignore the fact that diversity within this ethnic group is vast.

![]()

Xactly

Steep racial wage gap remains

The wage gap for Black and Hispanic or Latino workers has narrowed since the early 2000s, thanks in part to a tight labor market, the heightened focus on racial equity in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement, and the rising minimum wages in many states for jobs disproportionately held by Black and Hispanic or Latino workers.

But when you look back further, the wage gap for Black workers grew between 1979 and 2023, similar to overall wealth gaps between the rich and poor. The EPI analysis found that median wages for Black workers rose just 5.2% from 1979 to 2019, compared to 20% for white workers. And since 2010, the wealth gap between Black and white families has grown consistently, reaching about $240,000 in 2022, according to a Brookings analysis of Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances data.

Rising high school and college graduation rates among Black Americans—landmarks that typically pave the way for higher employment and earnings—have done little to narrow the wage gap or to address the higher rates of unemployment among Black workers.

EPI’s study found that Black college graduates saw their wages fall from 2015 to 2019 while wages for white college graduates rose. Educated Black workers are also often more likely to be unemployed than white workers with less education.

The Hispanic or Latino earnings gap was significantly steeper in 2000 and has shrunk by nearly 9 cents on the dollar since then. From 2019 to 2021, the Hispanic or Latino median household income grew by 2.7%, the highest of any racial group in that time frame. Still, the wealth gap for Hispanic or Latino and white households isn’t much better than the Black-white gap, at about $223,000 difference, according to Brookings—though wealth can look drastically different among the many populations classified as Hispanic or Latino. Hispanic or Latino people have also seen a significant rise in high school graduation and college enrollment but continue to earn less despite it.

Many Hispanic or Latino workers in the U.S. have to contend with complicated immigration policies to live and work in the country. These hurdles, paired with language barriers and discrimination, further pigeonhole Hispanic and Latino workers into low-wage occupations, limiting their earnings potential and ability to build and pass on wealth.

However, researchers have found that race—namely, being white or Black—has a much more significant influence on employment and income than Hispanic or Latino ethnicity alone. A 2019 report from Duke University, Ohio State University, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development found that white Hispanics had much higher incomes and lower unemployment rates compared to Black Hispanics in the Miami metropolitan area.

In addition to race and ethnicity, pay gaps persist based on gender, sexuality, and disability. The economic disadvantages compound, as well, with Black and Hispanic or Latina women earning even less on average than their white or male counterparts.

Changes must come from the top

EPI’s analysis found that to interrupt the cycle, governments and companies must intervene directly and intentionally to create pay equity.

In the past, civil rights legislation and anti-discrimination policies were followed by greater racial parity in pay. The EPI report suggests policies that would require employers to report employment and compensation data by race, ethnicity, occupation, and gender to create more transparency at an individual workplace level. The authors also recommend more funding to investigate discrimination charges, revising anti-discrimination laws, and more legal protections for those who speak out against workplace discrimination. A Brookings analysis suggests reparations from the public and private sector, or implementing tax policies based more on wealth and income.

However it’s achieved, racial pay equity cannot happen organically. It requires action to address historic and continuing patterns of discrimination throughout the U.S. economy and society.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Xactly and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.