25 photos of what Paris looked like the last time it hosted the Olympics

Published 6:45 pm Tuesday, May 7, 2024

25 photos of what Paris looked like the last time it hosted the Olympics

Following three unsuccessful bids over 25 years, the 2024 Summer Olympic Games are returning to Paris, with an estimated 300,000 spectators expected to watch the opening ceremonies on July 26. The city hosted the Summer Games twice before: in 1900, as the first location outside Greece, and then again in 1924.

Much has changed in the 100 years since the last Paris Olympics. Over 10,000 athletes from 206 different countries are slated to compete—that’s more than triple the showing in 1924. Today’s Olympics also contend with issues that were unheard of a century ago: Billions of anticipated cyberattacks, security concerns around massive crowds gathering openly, and efforts to cut carbon emissions in half are central to planning for the 2024 Games.

Over 30 venues across Paris and other nearby cities will serve as sites for the Games, including the Seine River and a temporary stadium and arena erected near the Eiffel Tower in the Champ de Mars. The city even invested more than $500 million to restore the Grand Palais, originally built for the 1900 World Fair. Although many Parisians have expressed displeasure about their city hosting the games, there is also hope that the 4.5-billion-euro budget used to update city infrastructure will rejuvenate areas like Seine-Saint-Denis, a neighborhood with historically high poverty levels that will contain the Olympic Village.

With excitement building for the 2024 Summer Games, Stacker dug through the archives to find photos of the 1924 Paris Olympics. Keep reading to see what the City of Love looked like a century ago—including iconic attractions like the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe—and learn more about 1924’s most memorable Olympic events.

![]()

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

An aerial view of Paris in 1928

While the Eiffel Tower remains one of the top tourist destinations in Paris, the Palais de Trocadéro no longer stands across the river as pictured here. Built for the 1878 World Exhibition, the palace overlooked the right bank of the Seine River for nearly 60 years until it was replaced by the Palais de Chaillot in 1937. The Trocadéro area in the city’s 16th arrondissement will host road cycling, triathlon, and other athletics events in the 2024 Summer Games.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Paris cafe society in the 1920s

1920s Paris was home to the “Lost Generation,” a group of artists, writers, and other creatives who escaped to the City of Light following World War I. Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Pablo Picasso were among those who gathered at sidewalk cafés like the one pictured here to work and mingle. Ernest Hemingway wrote most of his debut novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” at La Closerie des Lilas and was known to join E. E. Cummings for drinks at Café de Flore—cafés that both remain open and thriving in 2024.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

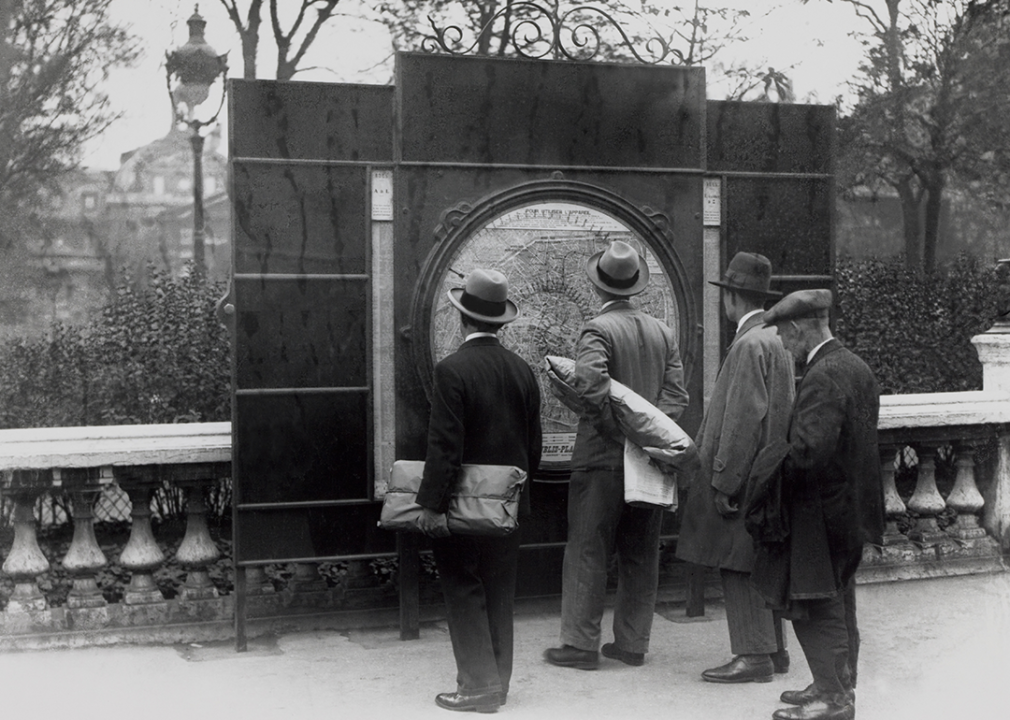

A look at a Parisian street map in the 1920s

Spectators traveling to Paris for the 1924 Olympics likely depended on roadside maps, like the one pictured here, to help guide them to the Stade du Matin for football, rugby, and track and field competitions or to the Piscine des Tourelles for swimming events. A century later, technology makes navigating the most highly populated city in France much easier, as cellphones provide on-demand directions via GPS, and public transportation information is posted on the Olympics website.

LL/Roger Viollet via Getty Images

Place de l’Etoile in the 1920s

Home to the Arc de Triomphe, the Place de l’Étoile is a roundabout where a dozen large streets—including the well-known Champs-Élysées—converge, forming the shape of a star. The square was renamed Place Charles de Gaulle in 1970 following the death of the former French president and has undergone renovations to benches and sidewalks in preparation for the 2024 Games.

Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

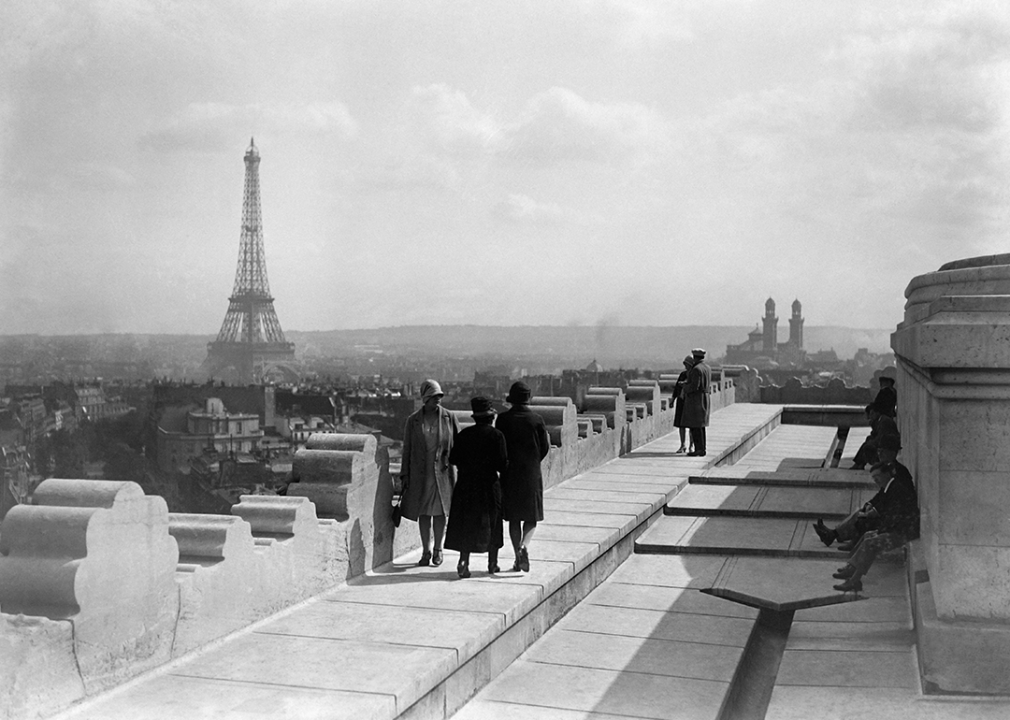

Tourists on top of the Arc de Triomphe in 1929

In this image, tourists take in the breathtaking view of Paris from atop the Arc de Triomphe. Twice the size of Constantine’s Roman arch, it was built as a monument to the victories of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. A list of battles won and generals’ names are inscribed upon the arch, and in 1921, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was added in front to honor those who died in World War I.

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock // Getty Images

The view under the Eiffel Tower in the 1920s

While in town for the 1924 Olympics, visitors were also able to visit the Eiffel Tower, much like the woman pictured here strolling underneath the 1,000-foot-tall structure built in 1889. Spectators arriving for the 2024 Games will enjoy the added bonus of a light system that was added in 1985: A beacon atop the tower shines across the city in the evening, along with 20,000 golden lights that sparkle for five minutes each hour. Athletes will even have the opportunity to take home a piece of history, as small pieces of scrap iron from the tower are embedded in the Olympic medals.

Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Travelers departing from Gare Saint-Lazare in 1929

Travelers mill around the departure board at this train station built in 1837 and famously captured in a dozen paintings by impressionist Claude Monet. One of six Paris stations, Gare Saint-Lazare runs local and regional trains that carried spectators around the city during the 1924 Games and will do so again in 2024. An estimated 1,600 trains run through each day, and the center also features dining and shopping.

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Painters on the Seine in 1929

For decades before the 1924 Paris Olympics, now-famous artists like Vincent van Gogh and Georges Seurat were inspired by life along the Seine River. Much like their predecessors, the late-1920s artists pictured here line the river to capture Notre Dame—one of the first Gothic cathedrals, which took 300 years to complete. While spectators at the 2024 Paris Games won’t be able to see Notre Dame, which was devastated by a 2019 fire, the landmark is well on its way to its grand reopening currently slated for December 2024.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

The Place de la Concorde in 1928

The Place de la Concorde is rich with history: It boasts a 3,300-year-old Egyptian obelisk made of pink granite and was the site of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette’s beheadings. Although it is Paris’ largest square, the traffic pictured here in 1928 is minimal compared to today. Great crowds are expected to flock to four arenas in La Concorde Urban Park to watch basketball, breakdancing, BMX freestyling, and skateboarding during the 2024 Games.

Bettmann // Getty Images

The Rue Lepic, in the center of Montmartre, in 1926

People line the streets of Rue Lepic in this image of a hilltop neighborhood located in Paris’ 18th arrondissement. Known for landmarks like the Moulin Rouge dance hall and the city’s red light district, Montmartre was home to acclaimed artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pablo Picasso. Sports fans may be surprised to learn that between 1912 and 1952 the Olympics included fine arts competitions, awarding 151 medals to various musicians, painters, sculptors, and writers.

Fox Photos // Getty Images

Le Bourget Airport in 1929

Planes line the runway of Le Bourget Airport, located nearly 5.6 miles (7 km) outside the city, on the 10th anniversary of the air service connecting London to Paris. The airport officially opened just five years before the 1924 Olympics and made history in 1927 when 200,000 people gathered to watch Charles Lindberg land from his cross-Atlantic flight. The city of Le Bourget boasts one of just two new venues built specifically for the 2024 Summer Olympics: a climbing facility that will remain open to locals after the Games.

Harlingue/Roger Viollet via Getty Images

A bus used to transport people to the Olympic Stadium of Colombes in 1924

Efficient transportation was critical to ensure that more than 600,000 visitors were able to successfully navigate Paris during the 1924 Olympic Games. The Métro system was one frequently used means of transport, as were autobuses. The bus pictured here carried spectators to the Olympic stadium in Colombes, approximately 8.2 miles (13.2 km) outside Paris.

Topical Press/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

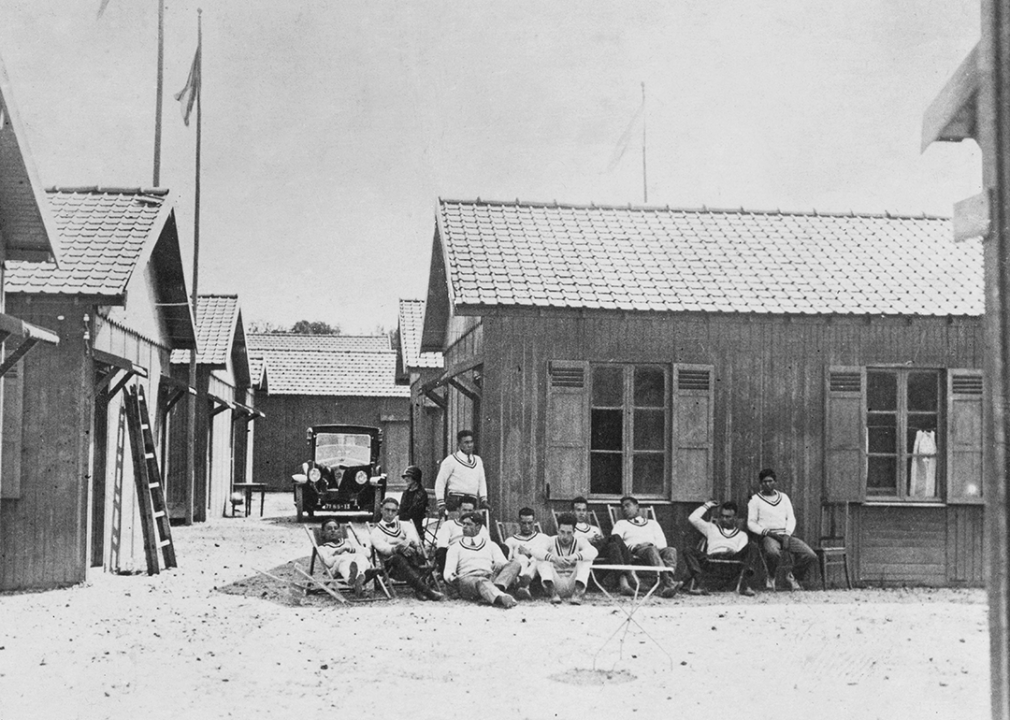

The Olympic Village at the 1924 Games

The 1924 Summer Olympics marked the inception of the now-standard Olympic Village. Most of the over 3,000 athletes competing in the Games stayed in small wooden cabins built a few minutes from the stadium in Colombes. The athletes’ village also featured other conveniences, including a hair salon, a post office, and a restaurant.

WWP/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

The opening ceremony at the Stade Olympique Yves-du Manoir in 1924

Spectators at the Stade Olympique Yves-du Manoir watch athletes from Great Britain participate in the opening ceremony’s Parade of Nations. Built in 1883, this stadium hosted events like marathons and rugby in 1924 and will make history in 2024 as the only French venue used for two Olympic Games, this time hosting hockey.

Central Press/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

The Prince of Wales and the president of France during the opening ceremony in 1924

Newly elected French President Gaston Doumergue and Prince Edward of Wales sit together to watch the opening ceremony on July 5, 1924. Doumergue remained in office for seven years while Prince Edward went on to become King in 1936—but only for a year before abdicating the throne following controversy around his engagement to Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American socialite.

WWP/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

British Olympians lay a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

While in Paris to compete in the 1924 Games, two athletes from Great Britain paid tribute by laying a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, located below the Arc de Triomphe in the Place de l’Étoile. The body of an unidentified French soldier was buried here on Nov. 11, 1920, to honor the unknown among the 1.4 million French soldiers who died fighting in World War I.

Bettmann Archive // Getty Images

The opening soccer match of the 1924 Summer Olympics

This photo gives a bird’s-eye view of the Stades de Colombes during the first football—or soccer, as it is known in the U.S.—match of the 1924 Games. For the first time in the history of the Olympics, this competition was organized as a single-elimination tournament among the 22 teams competing, with Uruguay taking home the gold medal.

Bettmann // Getty Images

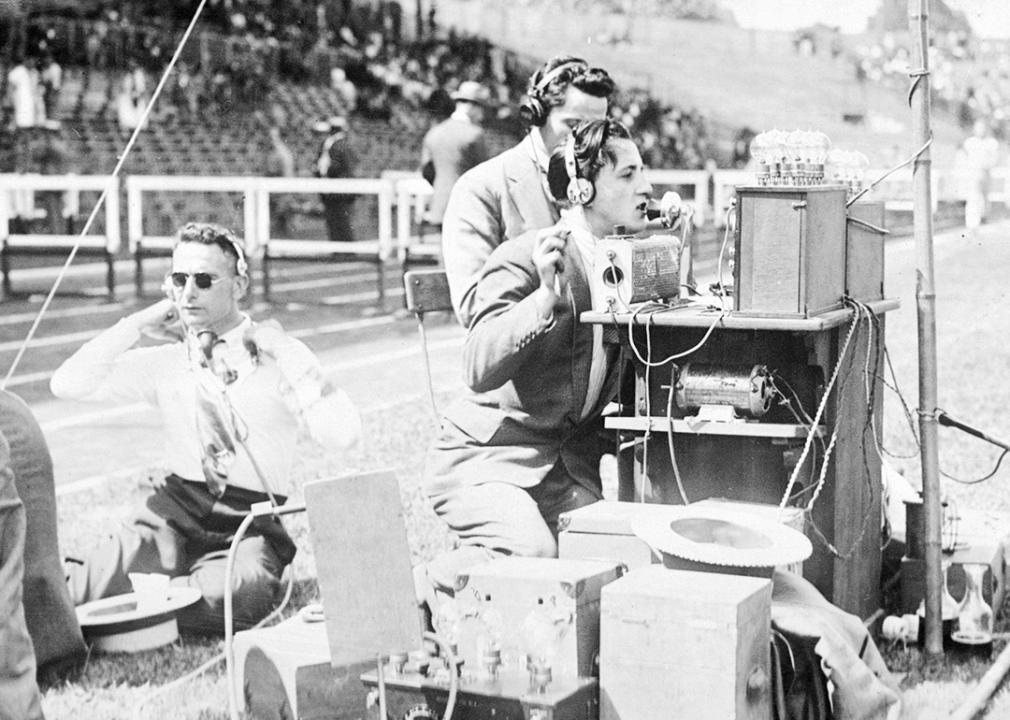

The radio station at the Colombes Stadium during the 1924 Olympics

Radio was a groundbreaking form of communication during the 1924 Olympic Games. As pictured here, an announcer at the Stades de Colombes received race updates by phone from along the marathon route, then shared this information over loudspeaker with spectators in the stands. This also marked the first time Olympic events were broadcast live via radio—although primarily within France, not internationally.

Bettmann // Getty Images

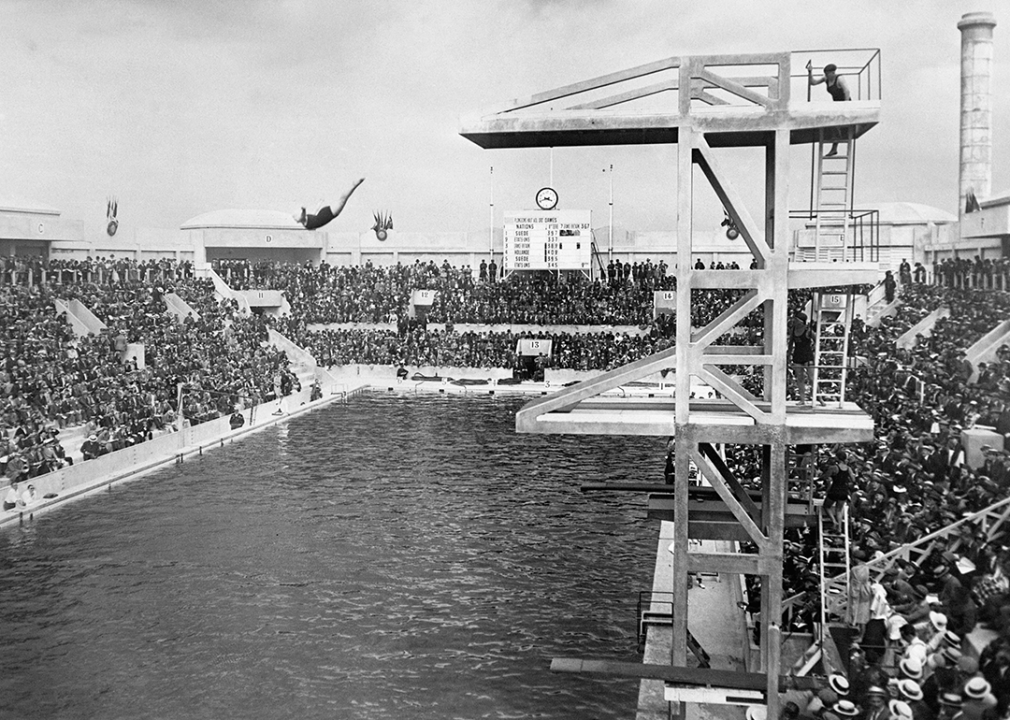

The high dive competition at Tourelles Pool at the 1924 Paris Olympics

American athlete Caroline Smith dives for gold, winning the 10-meter high dive event at the 1924 Summer Olympics. Swimming competitions were held at Piscine des Tourelles, a venue built specifically for this occasion, which boasted the first 50-meter Olympic pool with cork floats dividing the lanes. The venue will be used for training in the 2024 Paris Games.

Bettmann Archive // Getty Images

The 1924 US Olympic rowing team

The Philadelphia-based rowers pictured here represented the U.S. in the 1924 Olympic Games, covering canoe, four-oar, singles, and doubles events. The team was captained by James S. Rockefeller, great-nephew of oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller. Among other medals, the U.S. rowing team took gold in the eight-man race with Benjamin Spock on board—a man who would go on to become the pediatrician famous for penning “The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care” in 1946.

Bettmann // Getty Images

A US discus thrower at the 1924 Olympics

U.S. track and field team member Lemuel Clarence “Bud” Houser sets a new Olympic record, throwing the discus an impressive 46.155 meters to beat his nearest competitor by over a meter. Houser took home double gold medals—also winning the shot put—a feat no other athlete has achieved in the 100 years since.

Central Press/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

The long jump event at the 1924 Summer Olympics

On July 8, 1924, American William DeHart Hubbard became the first Black athlete to win Olympic gold in any individual event—an accomplishment he predicted in a letter written to his family just before setting sail to France for the games. Hubbard bested his long jump competition by leaping 7.445 meters to clench the victory.

Bettmann // Getty Images

US Olympic swimmers at the 1924 Games

U.S. Olympic swim team members Johnny Weissmuller and Duke Kahanamoku share a happy moment at the 1924 Games, where they won gold and silver, respectively, in the 100-meter freestyle. Both athletes had prolific careers outside of their multiple Olympic appearances: Weissmuller went on to star as Tarzan in a dozen films and Kahanamoku acted in 28 films while also championing the sport of surfing across the globe.

Central Press/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

A cross-country event at the 1924 Summer Olympics

A trio of Finnish athletes—Paavo Nurmi, Ville Ritola, and Edvin Wide—are pictured alongside other runners competing in an individual cross-country race held in Colombes on July 12, 1924. Nurmi, who won this event, made Olympic history by becoming the first athlete to win gold five times at the same games. Ritola placed second in this event and took home five additional metals: four gold along with another silver.

PA Images via Getty Images

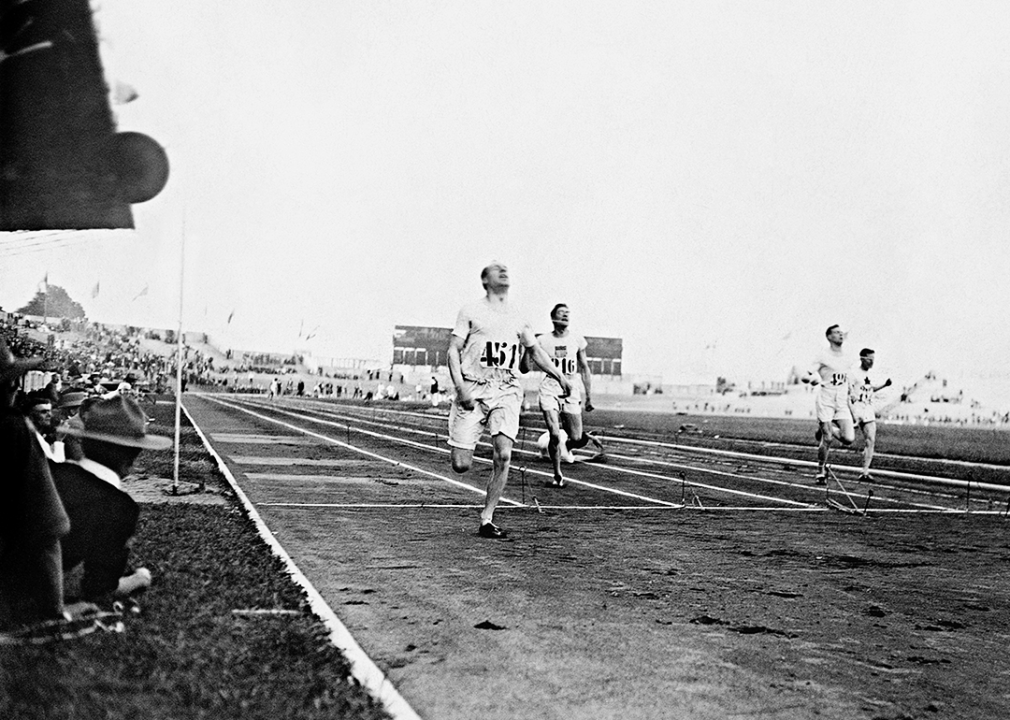

Eric Liddell, who inspired ‘Chariots of Fire,’ competing at the 1924 Paris Olympics

After refusing to participate in the 100-meter race based on his religious beliefs—as a Christian, he would not run on Sunday—British athlete Eric Liddell won gold in the 400-meter race pictured here. The story of Liddell and rival British runner Harold Abrahams—the country’s first Olympic winner of the 100-meter event, with a record time of 10.6 seconds—was memorialized in the 1981 Oscar-winning film “Chariots of Fire.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.