College costs are skyrocketing. Does attending a pricier school pay off?

Published 2:15 pm Wednesday, October 23, 2024

College costs are skyrocketing. Does attending a pricier school pay off?

As high school seniors across America prepare to make consequential college decisions, their parents might not be ready to let them leave the nest—or foot the bill. Among parents with a child attending college, fewer than half (44%) felt prepared to make the first tuition payment for their child, according to a 2024 survey from College Ave.

Published tuition fees have more than doubled over the last 20 years, and for many families, the cost of college is exorbitant and out of reach. Tuition for the typical public four-year college was roughly $22,000 annually during the 2022-23 academic year, while private nonprofit four-year colleges cost $53,000 per year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Although data from the College Board shows that the real cost of college (after factoring in inflation and grants) has actually fallen in recent years, the decrease is not enough to alleviate the sticker shock that students and their parents experience when planning for higher education.

Once acceptances roll in, families must weigh several factors, including cost, location, school culture, and prestige, before making their selection. However, the steep climb in college costs over time has amplified the importance of a critical question: Is it worth paying a premium for a more prestigious institution, or does a more affordable state school offer better value? Although many factors determine how much college graduates earn, a college’s ranking certainly plays a part.

Study.com analyzed data from the Department of Education and U.S. News & World Report to determine if going to a pricier college pays off.

![]()

Study.com

Do more prestigious schools mean higher pay?

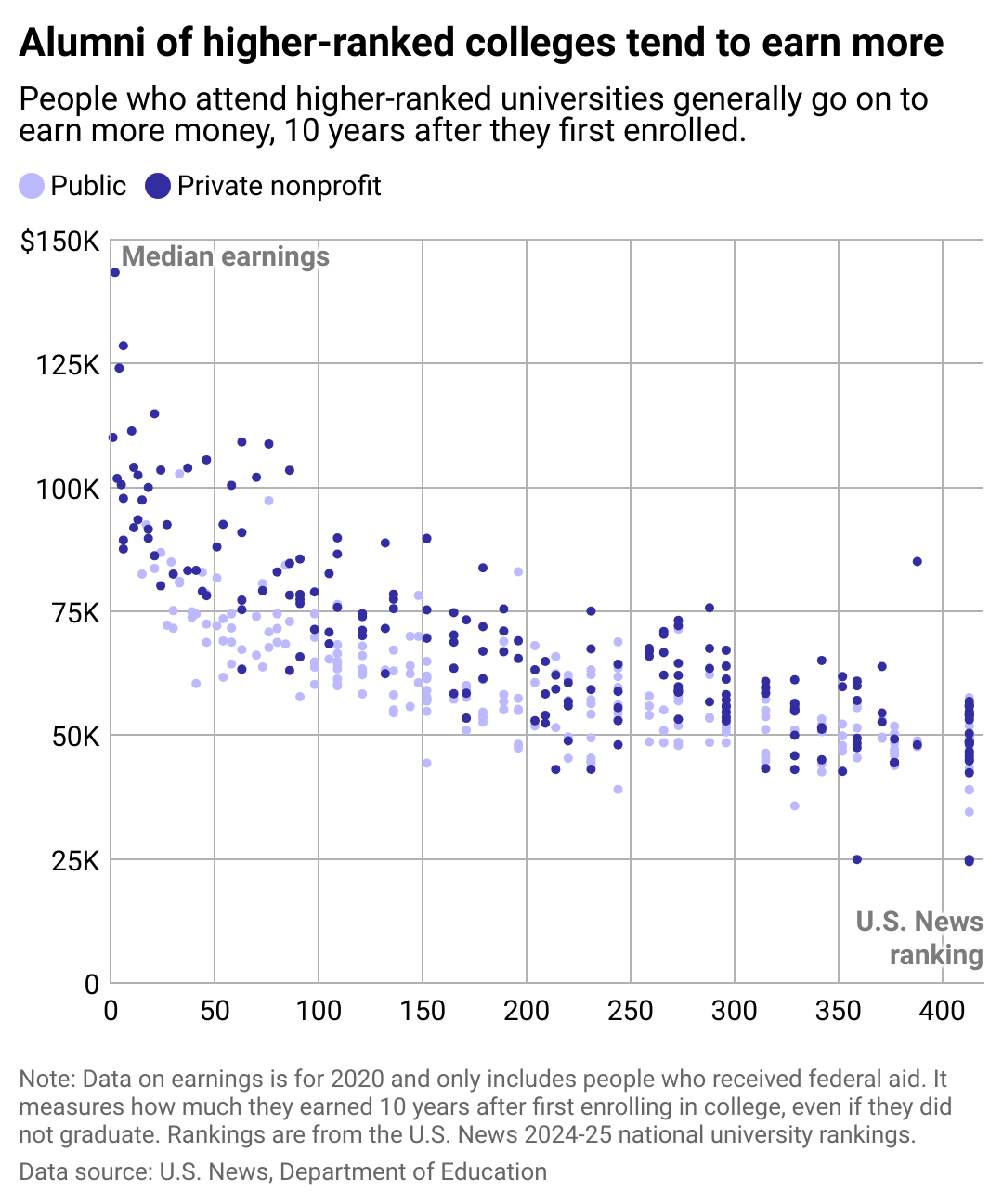

In general, people who attend higher-ranked colleges tend to go on to have higher earnings than those who go to less prestigious schools. Stacker’s analysis revealed that attendees of the top 10 universities in the nation, determined by U.S. News’ 2024-25 national rankings, make an average of over $100,000 a year, 10 years after first enrolling in college. In contrast, people who attended universities that were ranked between 100 and 200 only made around $65,000. This relationship holds true for both public and private nonprofit institutions, but with a notable private school premium when it comes to rankings and earnings.

Notably, earnings data from the Department of Education does have some limitations. The department only tracks the earnings of people who received federal grants, which means people from wealthier households who did not receive these grants may be excluded. This could make the earnings estimates of people who attended certain colleges unreliable, especially at institutions that have larger shares of wealthy students.

What’s more, the data on college costs only considers what’s in the database, which is the amount paid by the average student who received a federal grant. In reality, the amount each student pays for college will depend heavily on their family income. Because the numbers account for everyone who attended a given college—but did not necessarily graduate—some institutions could be taking credit for their dropouts’ success.

Choice of career, location, gender, and years on the job, among other factors, can affect how much graduates earn. For instance, data from the Census Bureau shows that Americans aged 25 to 64 with bachelor’s degrees earned an average of around $74,000 a year. However, graduates with the most lucrative major—electrical engineering—earned about $122,000 a year, more than twice what graduates with degrees in family and consumer sciences earned.

Study.com

Higher tuition does not always translate to a better job

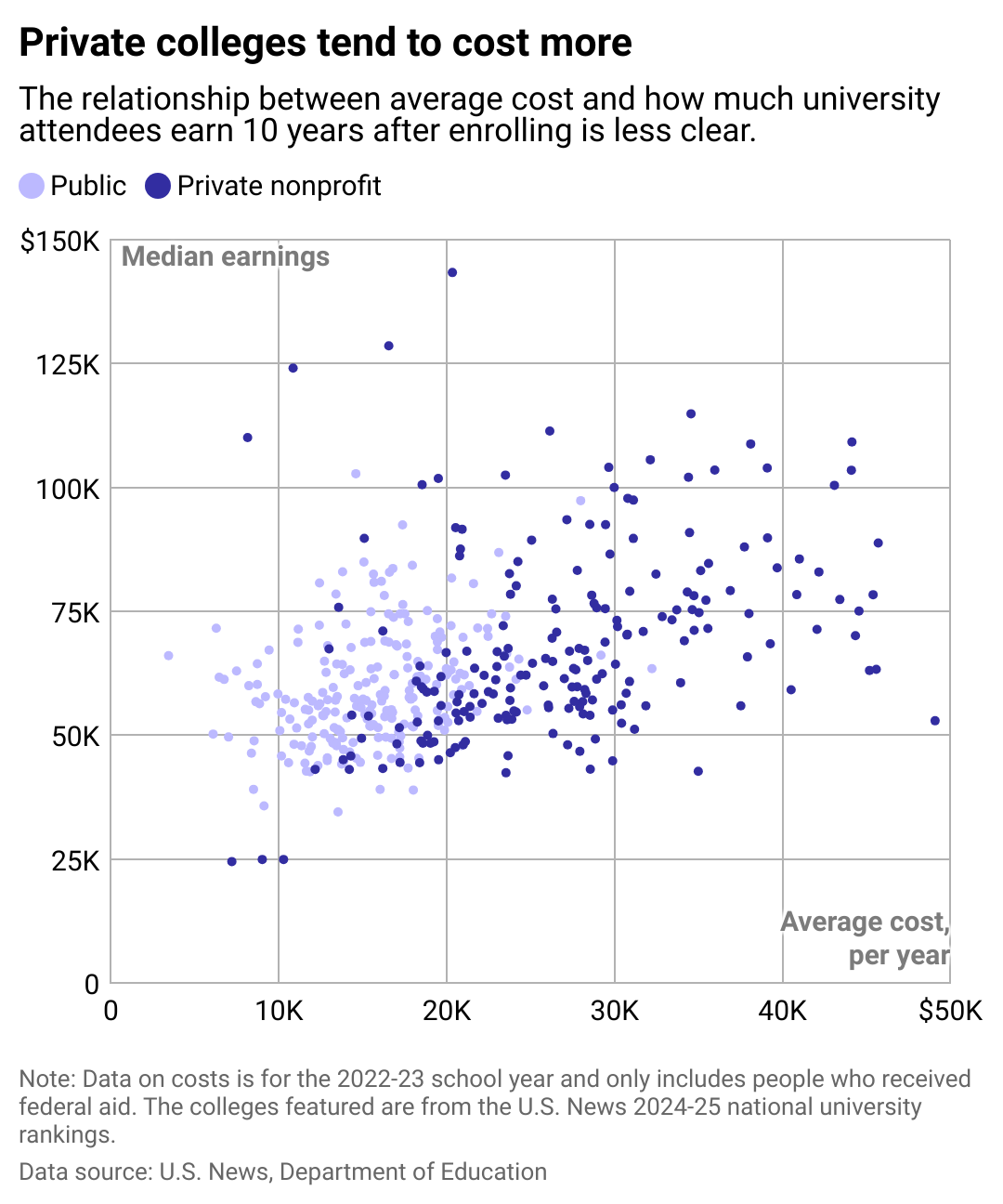

The data suggests that cost alone does not necessarily translate to higher earnings. How much graduates earn is also contingent on a school’s ranking. In part, this is because published college tuition fees depend mainly on whether a college is public or private, and not its overall rank.

Research in the late 1990s and 2000s by economists Stacy Dale of Mathematica Policy Research and the late Alan Krueger suggests that college choice might not have a significant impact on earnings. The researchers tracked the careers of students who were turned down from more selective colleges to attend less selective ones. Such students later ended up earning just as much money as their peers who did choose to attend higher-ranked colleges, according to research by Dale and Krueger.

The research found that Black and Hispanic students, as well as those whose parents had lower levels of education, tangibly benefited from attending higher-ranked colleges. These findings suggest that financial success later in life for some students is not due to their alma mater, but rather their inherent capabilities or the advantages of coming from more affluent households.

Earnings, however, are not the only metric of postgraduate success. A 2023 study by economist Raj Chetty at Harvard University and his colleagues found that while attending an Ivy League or comparable college, in general, does not significantly boost a student’s earnings, it does drastically raise their chances of reaching various forms of nonmonetary success. Going to a top college over a merely good state school almost doubles a student’s odds of attending a top graduate school, and triples their chances of working for prestigious institutions, according to the study.

The study also found that going to a top school increases a student’s odds of reaching the top 1% of the income distribution by 60%. So while a diploma from an elite institution might not help someone earn more money in a typical job, it does help them secure select jobs in fields such as tech, finance, and consulting that lead some professionals into the top 1%.

For high school seniors facing a pivotal academic and financial decision, it’s important to carefully consider both the long-term benefits and the possible financial burden of a particular college. Families can start by exploring federal and state resources to help navigate the complex U.S. financial aid system.

They can also estimate out-of-pocket college costs using a net price calculator, which looks at the price of a school after subtracting grants, loans, work study, and other aid from the published price. The differential between the sticker price and the actual costs can be quite significant—and, in some cases, have little bearing on what students actually pay.

Before immediately writing off the exorbitant cost of prestigious universities, parents should keep in mind that schools with large endowments are typically able to offer very generous financial aid packages, keeping the costs down for some students. Undergraduate students at Harvard, for instance, are expected to pay relatively little if their families earn less than $150,000, and nothing at all if their families earn below $85,000.

The bottom line: Students who want to make the best possible financial decisions should check thoroughly before deciding which colleges they can afford to attend.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on Study.com and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.