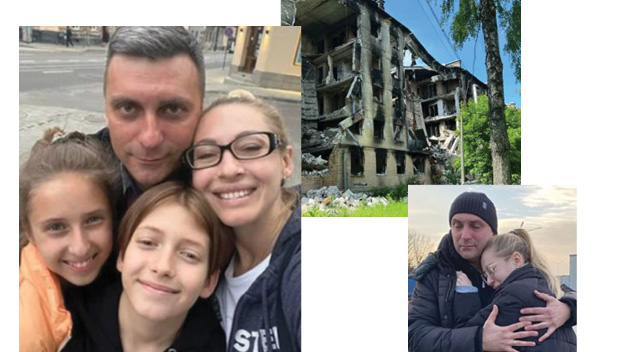

‘We survived’ — A Ukrainian family finds hope in small Mississippi town

Published 2:16 pm Saturday, July 23, 2022

“We would never wish this on anyone, but we survived.”

Ukrainian Olena Donchenko said this with a nod as she sat in the Brookhaven living room of her longtime friend Callie Davis. Her 12-year-old twins, Marianna and Daniel, were nearby, as were Davis and her 13-year-old twins, Foster Grace and Smith Elle.

Olena talked about her family’s experience as their home city of Bucha, near the capital city of Kiev, came under attack — how they hid, how they helped and were helped by neighbors, their stress-filled exodus from the country, and their eventual arrival in Southwest Mississippi. Davis asked questions and commented on recounted events. Daniel spoke rapidly to his mother in Ukrainian and English, adding to her account, with the occasional few words from his sister.

The European trio is in the United States for two years under the United for Ukraine program. Sasha is arriving tomorrow, Friday the 22nd, completing the immediate family. Though he’s fluent in Ukrainian and Russian, he’ll need to learn English — Olena speaks all three — and both parents will have to find employment.

They are in Lincoln County due to a connection Olena made when she was just 15. As an exchange student to Florida, she became fast friends with Callie, who was a couple of years older. Olena was advanced in her studies, so they shared classes. The two kept in touch over the years, and when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 — as a major escalation of the years-long Russo-Ukrainian War — the two struggled to stay in contact.

Encouragement came from family and friends in Russia to relax and be grateful for the invasion. Russia was going to save them from the Nazis. Only fascists would be killed and everyone else would be liberated. The Russian propaganda even went so far as to claim Ukrainian soldiers were being treated with biological agents, turning them into “zombies.” But the Ukrainian people were targeted. Stores, schools and homes were destroyed. Bodies were piled up in the playground near the Donchenko’s home.

The Donchenko family retreated to the basement of their three-storey house — joined by two neighboring families — to hide from invading forces for what they hoped was a matter of days. They lost internet after a few days when the tower was destroyed, then electrical power. Water and gas lines were cut soon after.

They washed, boiled food, flushed the toilet and drank using water from a neighbor’s cistern. They tried to avoid anything that would alert passing soldiers of their presence in the home, using a weak flashlight cupped in the palm of a hand when necessary, hiding under a mattress when missiles and tanks threatened to drop the ceiling on their heads.

They drank a lot of tea. Daniel had a collection of something special to him — he’d picked up sugar packets from their travels, and kept them all in a box about the size of a shoebox. When the sugar for tea was all used up, Daniel volunteered his special collection for everyone to use. Though it might seem insignificant to someone outside the situation, for the 12-year-old boy it was a personal sacrifice.

Each morning, Olena would carefully go to the top floor of the house and stretch her cell phone high to get a signal, sending a message to a friend that they were still alive. Their location made it impossible to get past enemy soldiers unseen, unmolested, unharmed.

One morning she called her father-in-law. He told her they had 20 minutes to gather what they could and get to where the Red Cross would pick them up in buses and get them to the Polish border. Russia had agreed to a “green corridor,” a safe passage for families with children to flee. They had to put signs in the windows of their cars that said “Children” in Russian, and tie strips of white cloths to the antennas or other spots on the vehicles. The only white fabric they had was 12-year-old Marianna’s favorite pillow case, white with little cactus images on it. She gave it to her mother to tear into strips. Each twin had sacrificed something precious to them.

Now everything else they could take was stuffed into four suitcases — not knowing if or when they would be able to return home for anything more. Every family who rushed to meet the Red Cross now crept along in their marked vehicles toward Kiev, taking more than three hours to cover the 30-some kilometers. Once they arrived, they sat under the watchful gaze and guns of the Russian army for six hours, before being told the corridor would not be opened after all — the Red Cross was not going to be allowed in — and that they should return home.

“Something told me that would not be good,” Olena said, and she told her husband. Sasha spoke to a Russian soldier and asked him pointedly if the soldiers would shoot them if they simply drove away toward the border. The Russian considered this, and said they probably would not … if there were a large number of cars together.

Sasha talked with other families and they all agreed the “probably” was worth the risk. A caravan of approximately 200 vehicles slowly drove away without incident.

The Donchenkos found out later that soldiers ransacked their home and others nearby not long after their exit. Women and children were raped. Older men were killed and thrown into mass graves.

At the border, Olena and the children were allowed to cross, but Sasha’s paperwork was not complete. The “rules had changed,” they were told.

It took weeks of worry, work and compromise, but after a period of time for Sasha working in the Ukraine — in humanitarian efforts, for no pay — and the others trying to find work and more in Austria, doors opened through United for Ukraine. Sasha was allowed to meet his family in Vienna to bid them goodbye before the children and his wife flew to the U.S., once more not knowing if they would ever see each other again.

But now the Ukrainian family is reuniting in Brookhaven with Davis and her family. They arrived July 2.

Life is not yet “settled” but it is better. Daniel and Marianna are no longer listening to whistles and booms outside their home, identifying missiles, bombs and gunfire by their distinctive sounds. They have a safe place to sleep and play near a lake in a neighborhood unscathed by war. It’s all still fresh, though.

“I don’t think you’ve really slept since you’ve been here, have you?” Callie asked. Olena shook her head “no.”

“So many people have been so nice to us,” Olena said. “And the children have made new friends.”

The Donchenko twins will attend school with the Davis twins at The Reading Nook Academy. In the afternoons, Daniel and Marianna will attend a Ukrainian school online to keep up with their math, language and literature skills. Olena is in the long process of getting paperwork and applications complete in order to get a job. Sasha will have to learn English first.

“People keep asking us what they can do to help,” Davis said. “If they can, they can give financially to the Ukraine Scholarship Fund at The Reading Nook.”

The scholarship will allow the twins to attend the accredited school where they can have more individualized instruction. Day-to-day needs are being met by the Davis family and others — food, clothing and shelter.

As Olena looked at her phone, scrolling through photos of her family and their hometown, the pair of twins exited to the kitchen where they began preparing and eating lunch. Even as tears threatened to spill down her cheek, Olena smiled and talked about the good people who had assisted, expressed concern and prayed for them.

For this mom who studied abroad, started college at age 16, has raised her children in a multi-lingual environment, and planned her life years ahead, it is difficult not knowing what the future holds for her and her family.

“I planned everything, years ahead. And saved (money) for years,” Olena said. “Now all that is …” — she opened her hands as if tossing something away — “… gone.”

But there is hope, and it is easily seen in the smiles on the Donchenko family’s faces.