A look at the West’s megadrought

Published 5:30 pm Thursday, November 3, 2022

https://s3.amazonaws.com/stacker-images/10180X3A.png

A look at the West’s megadrought

The United States, specifically the Southwest, has not experienced a drought as severe as the one it is presently withstanding in roughly 1,200 years. Any drought lasting longer than 20 years is considered a megadrought. The American West is entering year 23 of devastating dryness, and by most measures, the situation is worsening. Experts say these conditions could last through 2030.

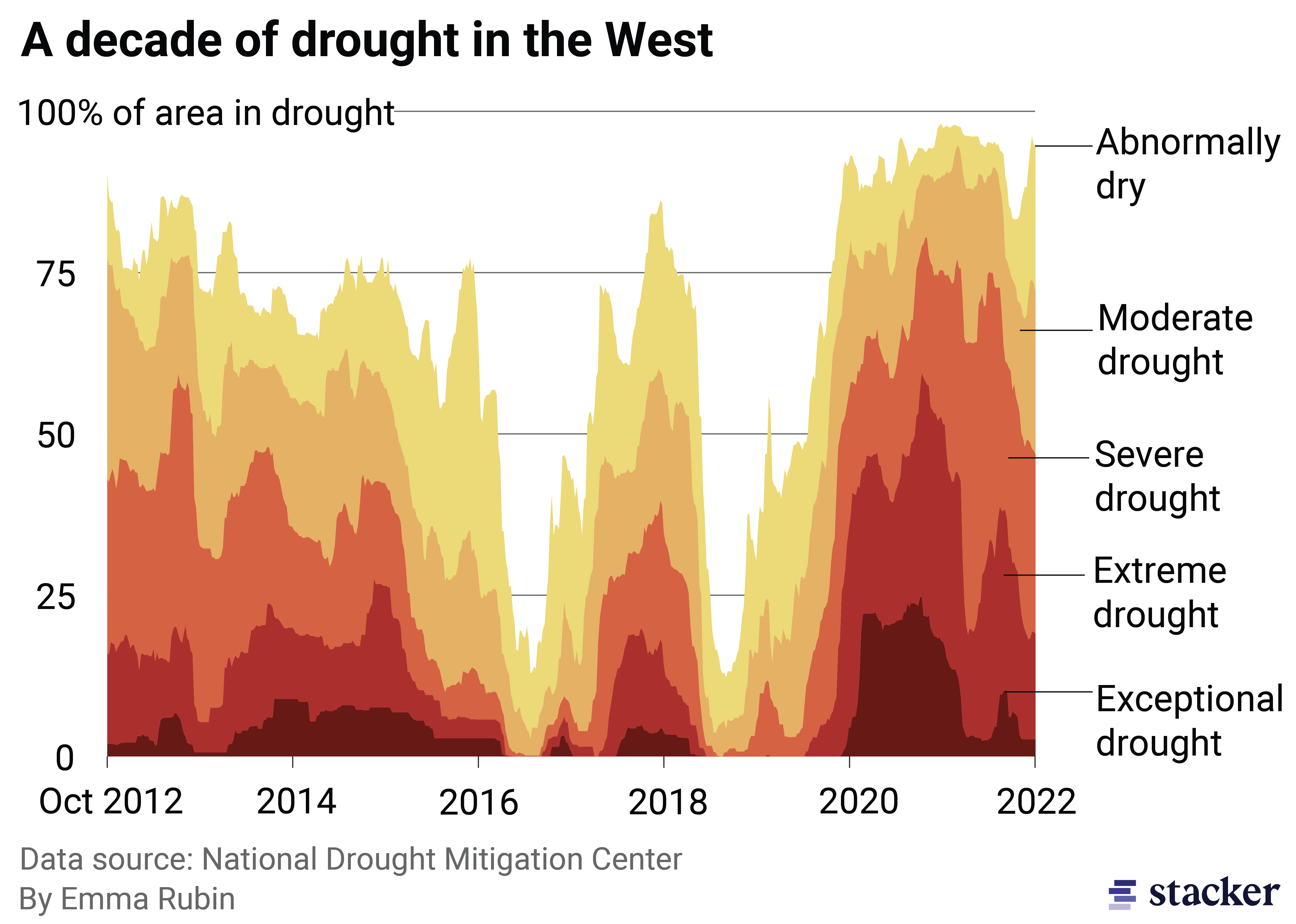

Between 2000 and 2021, temperatures in the West were, on average, 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than during the previous 50 years. As a result, about 75% of all land in the nine westernmost states in the continental U.S. are facing drought conditions; 35% of the land in those states is baking under drought conditions classified as extreme or exceptional. And while the situation is worst in the West, more than 80% of the U.S. is facing abnormally dry conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

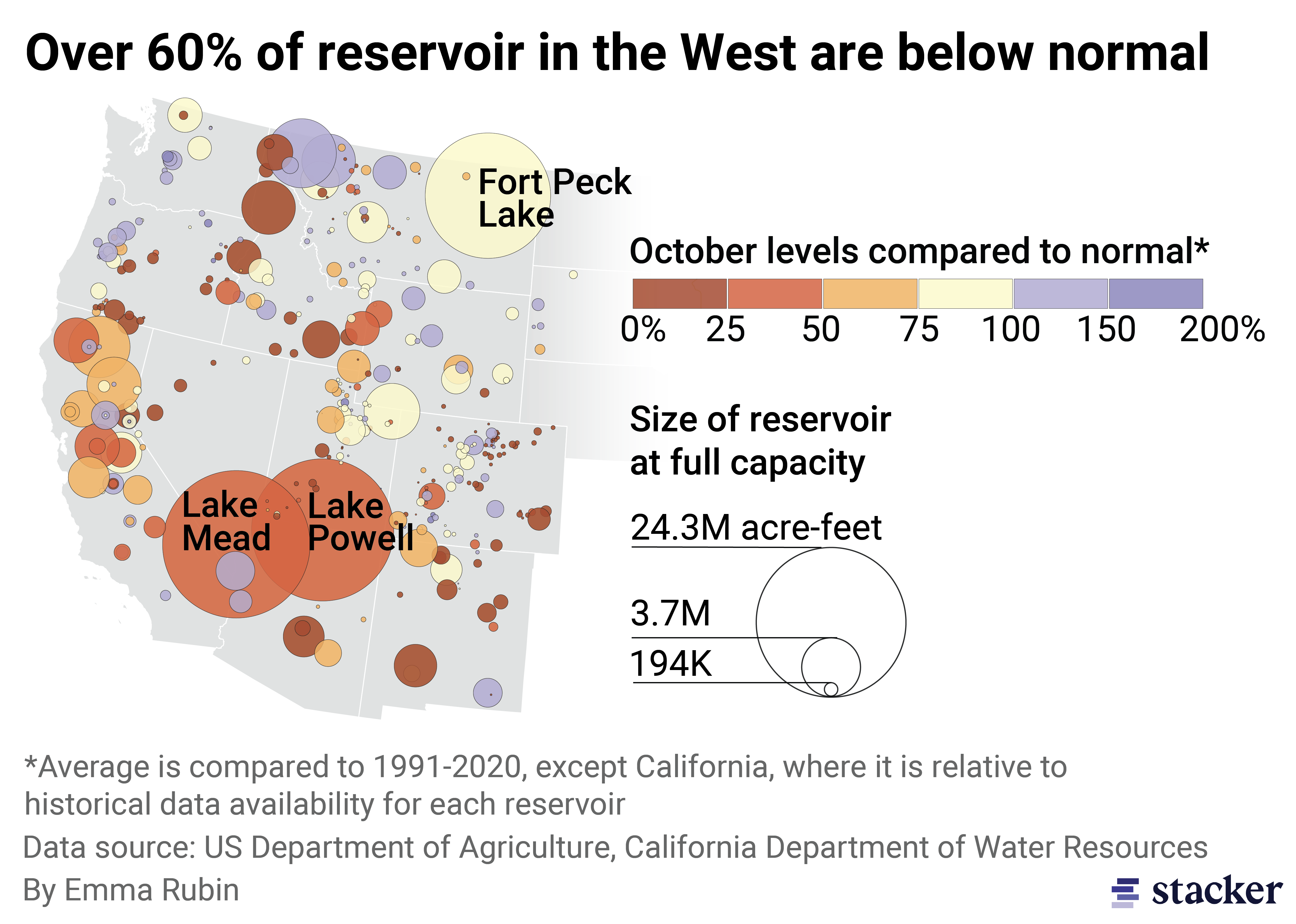

Major systems pivotal to daily life and economic stability in the West are under threat. The flow of the Colorado River, a lifeline for 40 million people in the upper and lower river basins, has declined by 20% since the start of the megadrought. Reservoirs along the river, like Lake Mead and Lake Powell, are central to agricultural and utility operations, and they are drying up at certain times of the year at a rate of 1 foot per week.

A 2022 UCLA study found that human-caused climate change has led to a 42% reduction in soil moisture, which is among the most serious consequences of drought. As temperatures rise, moisture is sapped from the soil, leaving behind poor-quality or unworkable farmland. Seasonal snowmelts, which help to quench dry lands, are happening earlier and faster and cannot adequately replenish moisture. Moisture reductions in the vegetation also lead to an increased risk of wildfires, turning entire landscapes into tinderboxes.

Droughts are likely to be a regular occurrence in the future. To better understand what our future might look like, and how we could be better prepared, Stacker cited data from the U.S. Drought Monitor, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the California Department of Water Resources to visualize the current megadrought in the West and its impact on the region.

You may also like: What summer weather was like the year you were born

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Almost all of the West is experiencing drought

Over a quarter of all land in the West experienced exceptional drought conditions during the summer of 2021. This designation is defined primarily by widespread and exceptional loss of agricultural lands like crops and pastures and water emergencies due to extensive reservoir, river, stream, and well depletion, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The central valley region of California, home to more than 5 million acres of farmland, is among the hardest hit by exceptional drought.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Low-reservoir levels impact water availability and hydroelectricity generation

Prolonged drought exacerbated by human-driven climate change is depleting reservoirs throughout the West. In California alone, nearly every major reservoir is below—often significantly below—historical averages, according to data collected by the California Department of Water Resources. Due to drought conditions, hydroelectric power in California was down by nearly 50% in 2021.

Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the two largest reservoirs in the U.S., recorded unprecedented low water levels in 2021. Over the last two decades, Lake Mead has been depleted from roughly 1,200 feet to 1,041 ft. If the reservoir falls below 895 feet, reaching what experts call “dead pool” status, water will not be able to flow downstream from the Hoover Dam, impacting hydroelectric capacity, drinking water access, and irrigation for more than 25 million people who rely on the lake for daily life. Experts believe this possible outcome is still years away.

To preserve the Colorado River system, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation announced the first-ever tier 2a shortage for Lake Mead in August 2022, instituting water usage restrictions for millions throughout lower basin states, including a one-fifth reduction in Arizona.

PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images

Dry landscapes heighten wildfire risk

As extreme drought dries out and kills plant life, this natural waste acts as vegetative fuel, or tinder, for wildfires. The buildup of this fuel, when ignited, can lead to hotter, larger fires that spread faster and burn longer. Carefully planned controlled burns executed by fire professionals are essential to maintaining a healthy ecosystem by clearing vegetative fuel, unhealthy flora, and overgrowth. The U.S. Forest Service has acknowledged the agency’s fire mitigation efforts have not matched the worsening conditions on the ground and, as a result, is committed to treating 50 million acres of government-owned, tribal, and private lands against wildfires. These intentional burns are not without risk, however. The largest wildfire in New Mexico’s history, which took place in May 2022, resulted from a controlled burn that escaped its confines.

Another factor that makes dry landscapes so dangerous and prone to wildfires is humans. People ignite about 85% of all wildfires in the U.S., often in regions called the wildland-urban interface where human development meets wild, often drought-ridden land. Highly desirable real estate regions in the West and Southwest, including the Sierra Nevada foothills, San Francisco Bay, San Diego, and San Antonio, have some of the largest swaths of land covered in this type of low-moisture vegetative fuel. In recent years, they have also experienced significant population increases, creating a volatile mixture of tinder and spark.

ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images

Farmers are confronting water scarcity

The agricultural industry in the American West is contending with severely low soil moisture, record-low precipitation rates, and severely reduced water allotments to irrigate farmlands. In 2021, drought in California led to economic losses totaling more than $1 billion, as well as the elimination of nearly 9,000 jobs for farmers and thousands more across upstream industries that touch the agricultural sector. According to the California Department of Food and Agriculture, about 400,000 acres of farmland were fallowed due to water scarcity.

In Texas, cotton farmers anticipate half a normal yield in 2022 and a loss of $2 billion. Drought impacts crops like cotton, grains, fruits, and nuts, as well as the pastures livestock farmers rely on to feed their herds. More than two-thirds of livestock farmers in the West have had to reduce the size of their herds and fallow rangelands due to water scarcity, according to a 2022 survey conducted by the American Farm Bureau Federation.

David McNew // Getty Images

Wildlife populations are also impacted

Food shortages, dehydration, habitat loss, and even biological changes induced by heat are all causes of declining animal populations in the drought-stricken West, with ripple effects echoing throughout the food web. The food supply for foraging species like the mule deer is dwindling and, as a result, so are their populations. Cold-water fish struggle to breathe in warmer, less oxygenated water and must compete for resources with invasive species that thrive in warmer temperatures. Less food availability means certain species cannot reach full maturity, which is critically important for animals like elk who use antlers—a sign of their physical maturity—to joust for territorial or mating rights. These environmental changes also push more species into contact and often conflict with humans as they seek water and food in the communities abutting their natural habitats.