While Narcan can reverse opioid overdoses in the short term, these two treatments can help patients overcome addiction altogether

Published 1:00 pm Monday, June 12, 2023

Hanson L // Shutterstock

While Narcan can reverse opioid overdoses in the short term, these two treatments can help patients overcome addiction altogether

Substance use disorder has reached a crisis point in the United States. The Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found in its most recent annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, reporting on the calendar year 2021 and released in January 2023, that 17% of adults met the DSM-5 criteria for having a substance use disorder. Some 5.3 million adults struggled with opioid use disorder, specifically, according to the report.

People suffering from substance use disorders must overcome countless obstacles when pursuing treatment, among them a societal stigma that, to this day, stems from obsolete 20th-century messaging that characterized addiction as a moral failure. Such judgments have widely persisted despite counterevidence and opposition from professionals in addiction research.

The medical community has long recognized that addiction is a disease of the brain that can begin and progress due to circumstances beyond the affected individual’s control, including biology, genetics, and environment. But stigmatization keeps many sufferers trapped in a cycle progressively damaging to their health and well-being. Moreover, while treatment options include everything from self-help groups to inpatient rehabilitation, less than 10% of those in need of treatment received it in 2021.

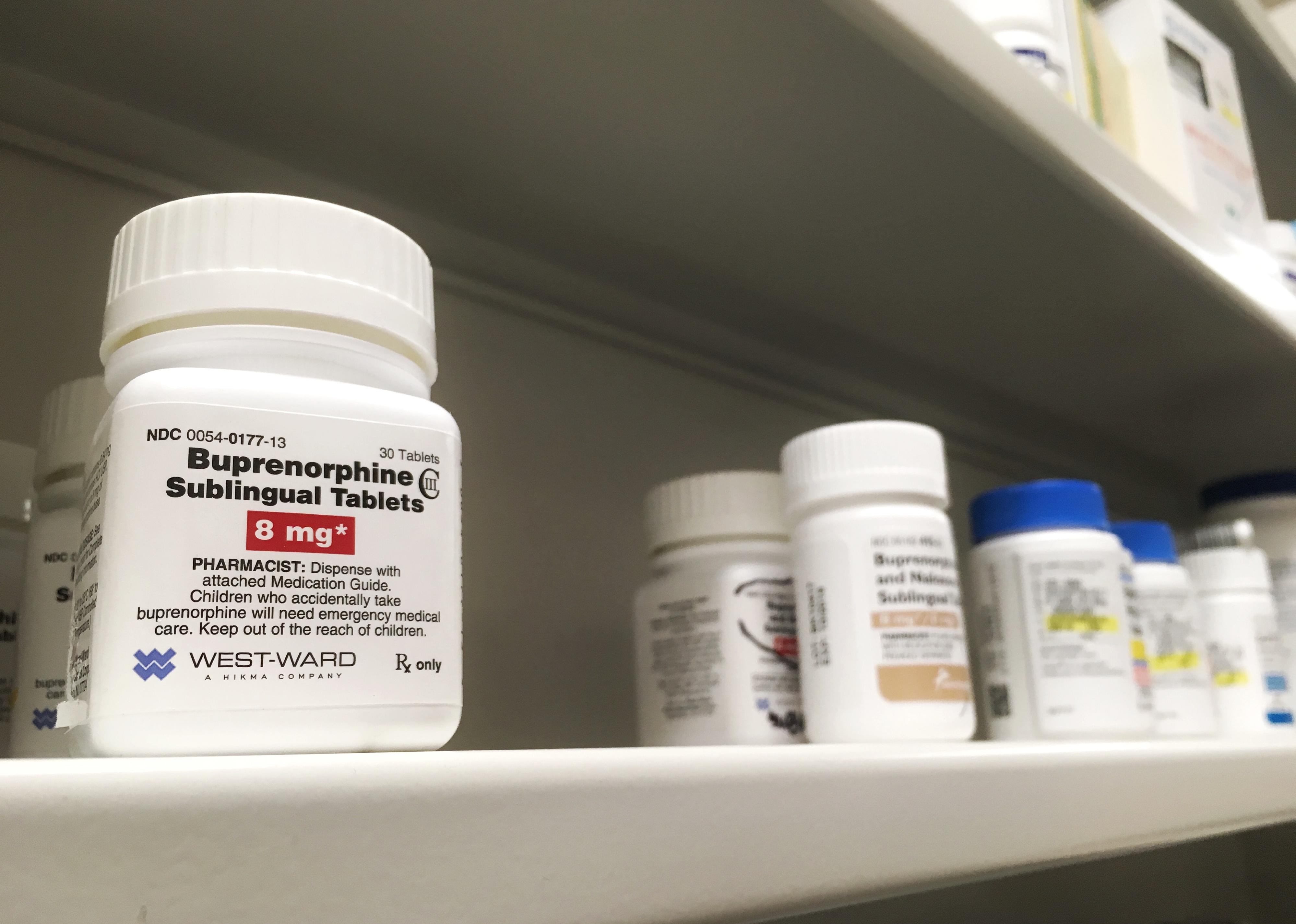

The recent Food and Drug Administration approval of naloxone nasal spray as an over-the-counter medication is expected to reverse the effects of opioid overdoses and reduce the number of related overdose deaths, but it won’t help someone struggling to overcome addiction itself. For that, many have found success with two medications long employed for the treatment of opioid use disorder: methadone and buprenorphine. The two drugs are not identical, and their differences can have a significant effect on the recurrence of heavy substance use and a person’s ability to treat their addiction successfully.

Citing medical journals, studies, and government resources such as the Drug Enforcement Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ophelia highlighted the differences between methadone and buprenorphine in treating opioid use disorder.

![]()

Bernard Chantal // Shutterstock

Methadone has been in use decades longer than buprenorphine

In 1937, German chemical company I.G. Farbenindustrie developed methadone as an alternative painkiller to opium. While the full scale of World War II had yet to come, the country was nonetheless facing an opium shortage due to its trade routes remaining under the control of Allied forces.

Shortly after the war’s end, in 1947, Eli Lilly and Company introduced methadone (under the name Dolophine) to the United States for analgesic pain relief. In the 1950s, researchers at the Narcotics Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, began studying the drug for its potential in treating opioid use disorder. Two decades later, in 1973, the drug received formal authorization from the FDA as a treatment option for several opiate-based substance use disorders.

Conversely, buprenorphine was not authorized for therapeutic use in the United States until 2002, more than three decades after British researchers first developed it in a quest to synthesize a powerful but nonaddictive pain reliever.

Kemaro // Shutterstock

While both are effective, the overdose risk of buprenorphine does not increase with higher doses

Treatment protocols for opioid use disorder incorporating either methadone or buprenorphine are significantly less likely to induce alternative substance misuse than abstinence-based treatment approaches. However, those treated with methadone tend to have higher rates of ongoing substance use than those treated with buprenorphine.

Neither medication will produce a “high,” but because methadone is a full opioid agonist, while buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, the opioid effects from methadone continue to increase with larger doses. Conversely, the opioid effects associated with overdose from buprenorphine plateau once a certain threshold is reached, regardless of whether more is taken.

Some formulations of buprenorphine include naloxone as an additional misuse deterrent. Because naloxone is an opioid antagonist—blocking opioid receptors before they can activate within the body—such formulations induce immediate withdrawal-like symptoms, rapidly reversing the effects of opioid overdoses. The immediacy of withdrawal can be physically unpleasant; consequently, treatments that employ a buprenorphine-naloxone combination act as a deterrent to the misuse of such treatments.

PureRadiancePhoto // Shutterstock

While methadone is more tightly regulated, buprenorphine can be prescribed for at-home use

Given the aforementioned differences between buprenorphine and methadone, it is unsurprising that methadone is more strictly regulated and less easily accessible. Methadone is considered a Schedule II substance under the Controlled Substances Act and may only be dispensed at a licensed clinic. Doctors in the US may not issue prescriptions for methadone to patients to treat opioid use disorder.

Conversely, buprenorphine is a Schedule III substance. It is legal for doctors, nurses, and other health practitioners who have obtained a DEA license to prescribe the medication to patients to pick up at a local pharmacy for at-home use. In the past, prescribers had to obtain a Data Waiver in order to prescribe buprenorphine; however, that requirement was dropped via legislation that took effect in early 2023.

This story originally appeared on Ophelia and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.