Inside the book-ban machine: The rise of 'parental rights' groups and their efforts to ban books

Published 5:10 pm Thursday, September 21, 2023

Inside the book-ban machine: The rise of ‘parental rights’ groups and their efforts to ban books

“Meet Mary IN THE School LIBRARY!

Mary has a dirty little secret.

She collects naughty children’s books!

Do you have a recommendation for Mary’s book collection?”

Thus reads the description for a Facebook group called Mary in the School Library Michigan, one of at least nine nearly identical groups in different states that ask concerned citizens to report books that could be “pornographic in nature, obscene, or harmful to children.” The ultimate goal, as written on its page, is to “help write and collect detailed and easy to understand book content reviews” and circulate these reviews to parents “so they can make informed decisions.”

At first glance, there is nothing particularly remarkable about the desire to keep pornographic materials out of the hands of minors. Closer inspection of “Mary’s book collection“—hosted on the website Rated Books—however, reveals several titles that would likely not meet the legal standard of what’s considered “pornographic” or “obscene,” including Heather Gale’s “Ho’onani: Hula Warrior,” Robie H. Harris’ “Who Has What? All About Girls’ Bodies and Boys’ Bodies,” and Harry Woodgate’s “Grandad’s Pride.”

Trending

The webpage also links to a national network of right-wing groups synonymous with book banning, including Moms for Liberty, Truth in Education, and No Left Turn in Education.

As attempts to ban books reach record levels, Stacker explored how organized efforts have enabled challenges on a larger scale than ever before at libraries and schools across the U.S.

This story is the second part in Stacker’s two-part series on the state of book bans in the U.S. Read the first part here.

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Conservative education groups have spread rapidly, frequently in areas with politically mixed populations

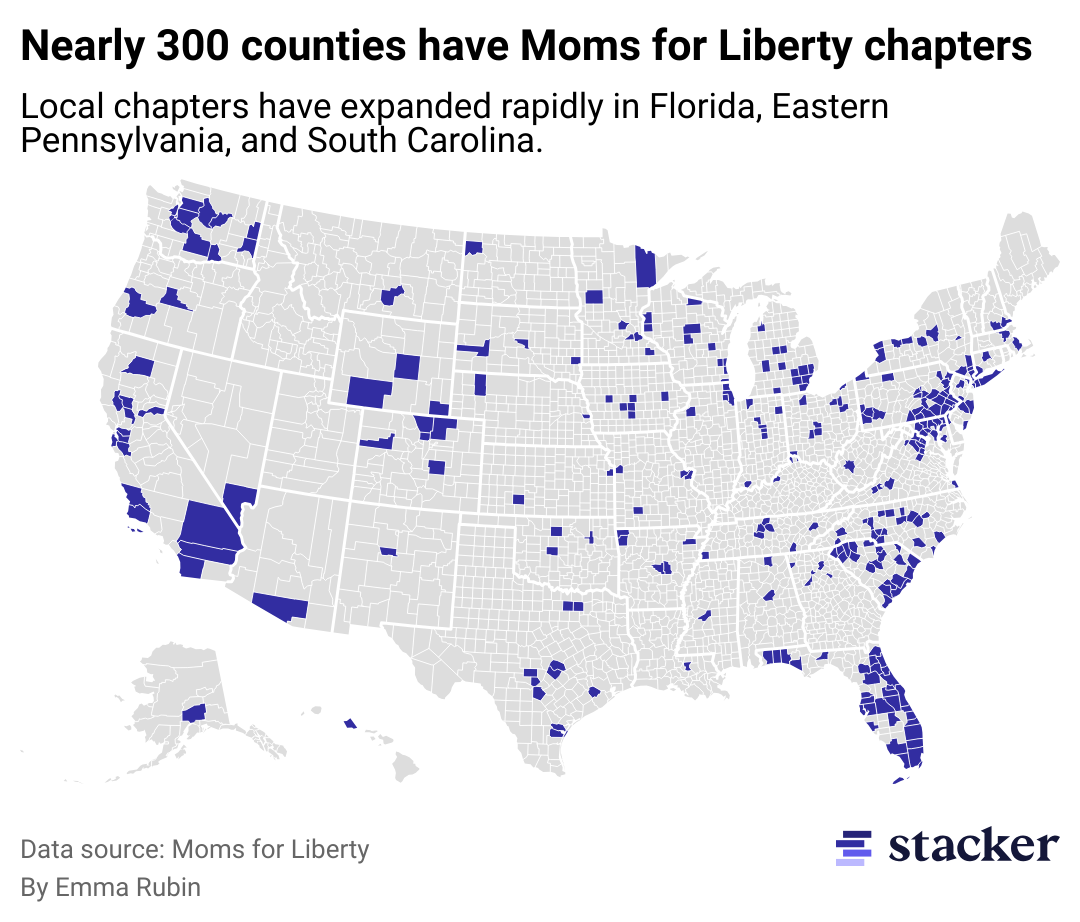

Since the self-proclaimed “parental rights” group Moms for Liberty was founded in 2021, it has established itself as a political powerhouse, with Republican presidential hopefuls like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and former President Donald Trump vying for its endorsement.

Moms for Liberty’s conservative reputation transcends Republican strongholds, with chapters mobilizing conservative voters in politically mixed areas. Nearly a third (30%) of its chapters are in counties where President Joe Biden won over half of the vote in 2020, according to an analysis of 2020 election data and Moms for Liberty chapter location data by Stacker. About another quarter (28%) are in more politically mixed counties where neither Trump nor Biden won at least half of the vote.

Trending

In addition to advocating against discussing racism and LGBTQ+ topics in classrooms, the group is perhaps best known for its campaign to restrict or ban books in public schools. Bolstered by funding from its conservative political action committee, members have gotten onto school boards nationwide, galvanizing supporters to challenge books.

Moms for Liberty co-founders Tina Descovich and Tiffany Justice confirmed that’s part of the group’s strategy, telling Stacker in an email that the group provides a toolkit to potential candidates “as a resource on how to run an effective campaign.”

Take, for example, Central Bucks School District in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It is the third-largest school district in Pennsylvania, a swing county in a swing state. The district is still navigating the aftermath of a 2021 school board election that saw a conservative majority ban several books, many of which with LGBTQ+ themes. The district has also faced state scrutiny for “fostering intolerance” by banning Pride flags and retaliating against staff who spoke out against the administration. In October 2022, the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania filed a discrimination complaint against the district for creating a “culture of discrimination against LGBQ&T students, particularly transgender and nonbinary students.”

Moms for Liberty has a strong presence in Bucks County, and members frequently attend Central Bucks school board meetings. Two Moms for Liberty members currently sit on the school board.

For Lela Casey, a mother of two students in the Central Bucks School District, the division sown by the school’s administration is a betrayal of the reasons she chose to raise her kids in the county in the first place.

People she used to feel a sense of neighborly camaraderie with, despite political differences, have become hostile, Casey told Stacker. When she attends school board meetings with her daughter, a freshman in high school, Casey said they both face harassment from the Moms for Liberty contingent.

The impact of the book bans and other policies is most strongly felt by LGBTQ+ students and kids of color in the district, according to Casey. “They’re the ones primarily who show up at meetings and say, ‘Look, these policies are hurting us,'” she said.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

New conservative book rating sites are fueling book bans

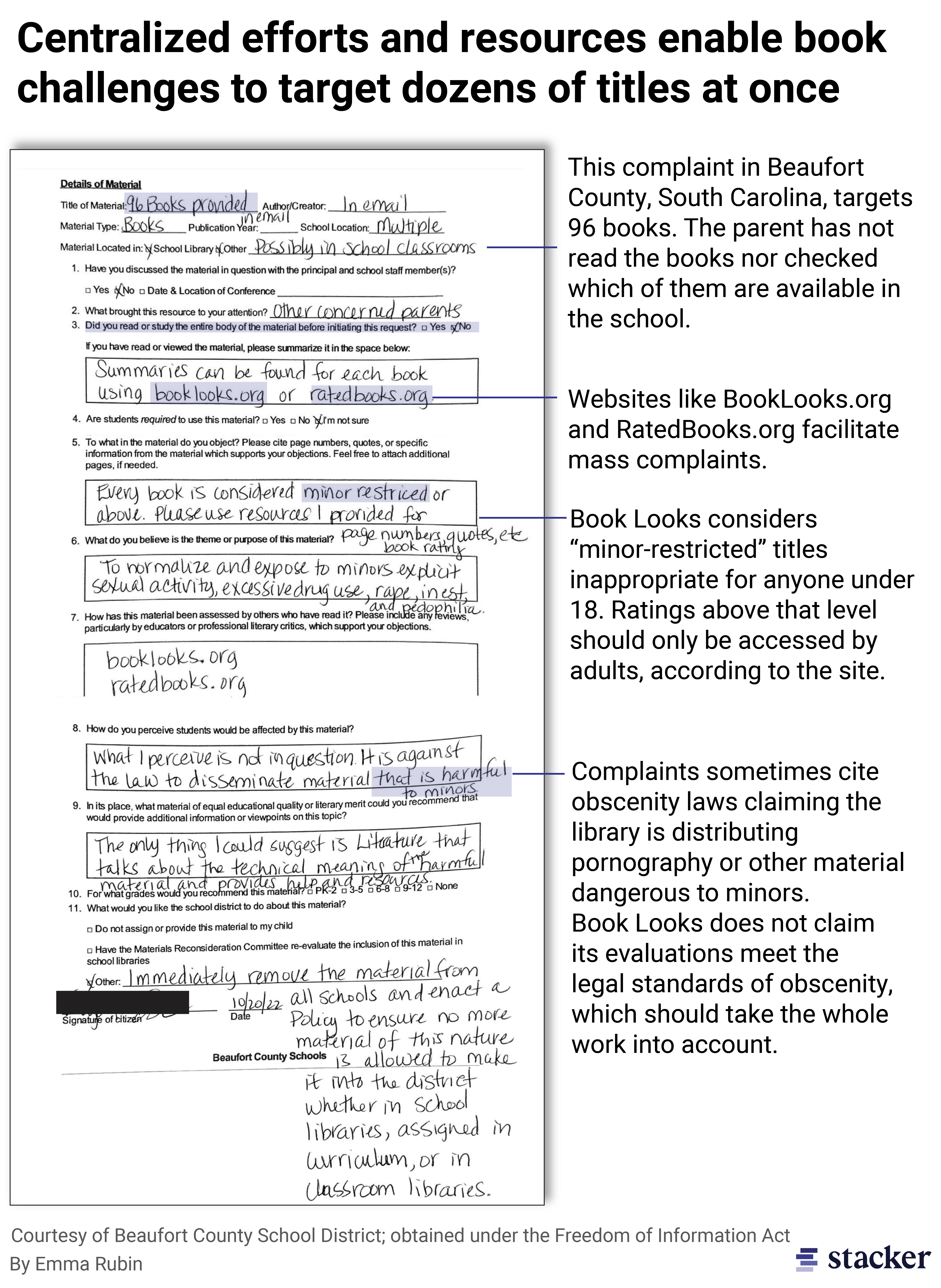

To challenge a book, most libraries have “request for reconsideration of material” forms, where patrons can ask librarians to reassess a book or other material. Forms often ask the complainant to describe the issue, cite specific passages they find inappropriate, and suggest actions for the library to take, such as removal of the books.

The questions these forms pose are intended to ensure people have actually read the materials and can lodge their complaints knowledgeably. However, an online ecosystem of conservative book ratings sites, Facebook groups, and artificial intelligence tools has allowed people to skirt that step.

One of these rating sites, Book Looks, provides reports for over 600 titles, including frequently challenged books like Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer” and Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give.” Its reviews contain prewritten summaries citing concerns like “alternate gender ideologies” or “inflammatory racial commentary,” page numbers of allegedly problematic passages, and a profanity count.

The undisclosed number of parents behind Book Looks claim on the website that they do not support book banning, but rather seek to be a source for parents who are “frustrated by the lack of resource material for content-based information regarding books accessible to children and young adults.”

Despite this assertion, Book Looks reports have been cited in countless attempts to remove books from libraries. The site’s founder, Emily Maikisch, told Stacker in an email that she was a member of Moms for Liberty from January to March 2022; she and her husband started Book Looks after she ceased her involvement in the group, citing different goals. Maikisch also said Book Looks operates independently from any other groups, though Moms for Liberty lists Book Looks as a resource for examining and challenging library collections. Descovich and Justice of Moms for Liberty also told Stacker that the organization “has no affiliation with any of these book sites in terms of helping to run them.”

Book Looks reviewers rate books on a scale of 0 to 5, classifying whether kids and teens should have access to the material. A score of 4 means no one under 18 should access the material, and 5 is considered “aberrant content.” (The full rating system can be seen here.)

Books in libraries and bookstores have long been shelved by age range, categorizing titles based on what publishers specify. Book Looks ratings frequently deviate from these standards, often citing culture war talking points that publishers wouldn’t consider inappropriate. As of Aug. 30, at least 3 in 5 young adult or teen books (61%) scored 3 (minor restricted) or higher, a Stacker analysis found.

Same-sex parents and mentions of racism are often grounds for Book Looks to give a picture or juvenile fiction book a rating of 1, or “child guidance,” meaning it isn’t appropriate for young children. Of the 133 picture and juvenile books rated “child guidance,” nearly half mentioned “alternate gender ideologies” in the summary of concerns, and at least a quarter mentioned “alternate sexualities.” “Racial commentary” was cited in 17% of the reports, like Lynda Blackmon Lowery’s “Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom.” Maikisch told Stacker that LGBTQ+ content is not a “major factor” in Book Looks ratings, but they want parents to be “prepared to provide the proper guidance.”

It doesn’t take much to receive a Book Looks rating that could drastically limit a book’s readership. Gregory Bonsignore’s “That’s Betty,” a picture book biography of Betty White meant for 4- to 8-year-olds, received a 1 rating from Book Looks because of two lines, effectively shutting out its intended audience. One referenced the backlash White received for featuring Black tap dancer Arthur Duncan on “The Betty White Show,” and another mentioned a character with two fathers.

More than a third of juvenile books, which typically target children up to age 12, were rated by Book Looks as “teen guidance,” meaning the content may not be appropriate for children under 13. Many of these feature transgender characters, mild violence, or nonsexual nudity.

One example is Sandy Kleven’s “The Right Touch,” a 1998 children’s book aimed at teaching kids consent and preventing child sexual abuse. Prolific Goodreads reviewer Randie Camp praised its “warm, safe, and comforting” illustrations; another reviewer described it as “gentle and helpful.” The book won the 1999 Benjamin Franklin Parenting Award from the Independent Book Publishers Association. By contrast, Book Looks flags passages containing nonsexual images of the bodies of boys and girls and a scene where a character shares a sexual abuse experience.

Book Looks also rates books intended for adults. Some are Colleen Hoover and Danielle Steele romance novels whose target audience isn’t children or teens. Others are books that might be found on a high school syllabus and are considered classics in literature, like Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye.”

Emma Rubin // Stacker

Regional groups are also organizing to challenge books: About 1 in 6 complaints nationwide in 2022 were from St. Tammany Parish

St. Tammany Parish Library is a system of 12 branches located just across the causeway from New Orleans. Kelly LaRocca, the library director, has served in various capacities in the system for the past 18 years. She told Stacker that book complaints used to be few and far between, amounting to roughly one every year or every other year.

Everything changed in June 2022, when a Pride display in the library’s Mandeville branch touched off verbal complaints about books with LGBTQ+ themes and an onslaught of what the library calls “statements of concern.”

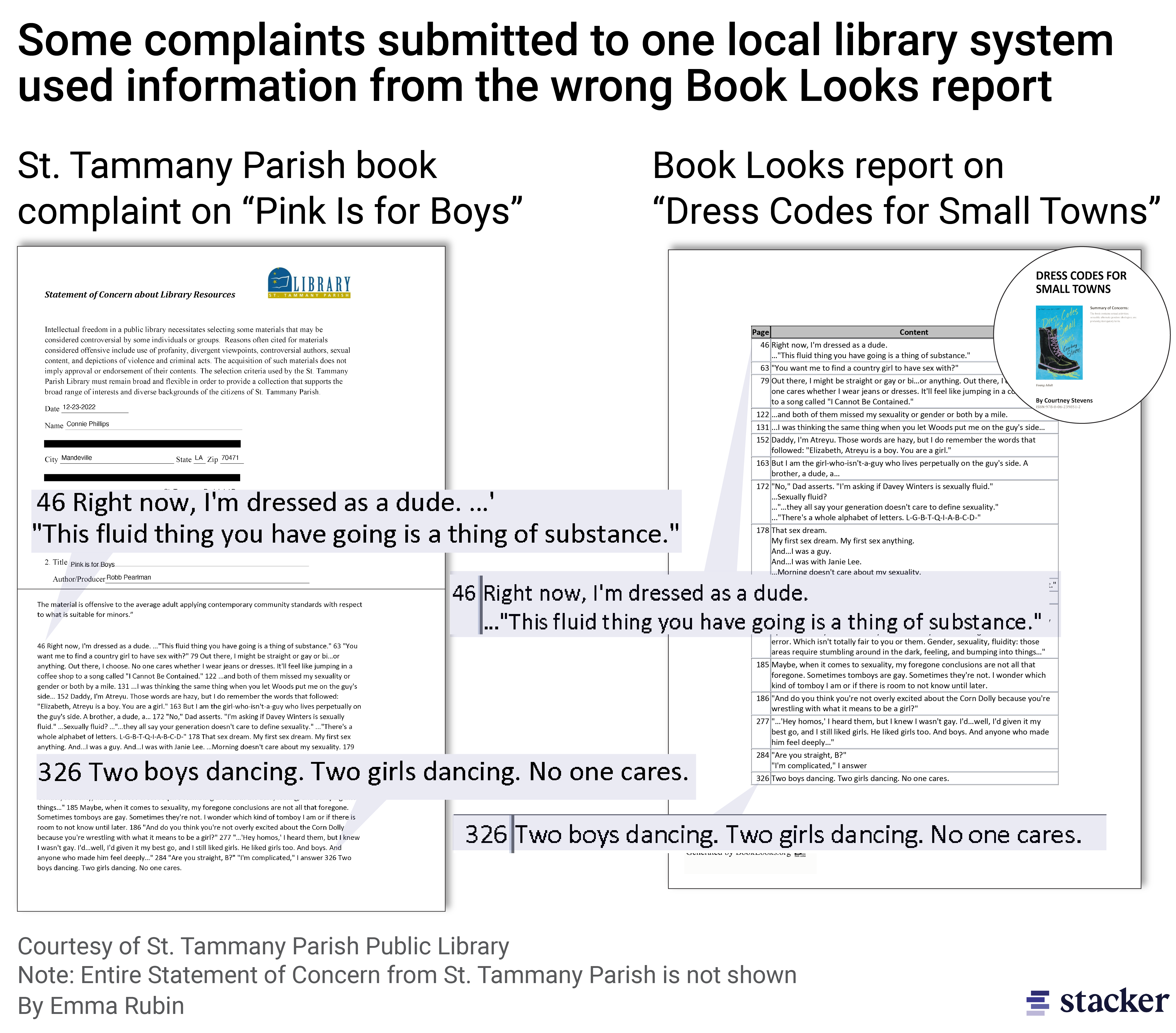

From August 2022 to September 2023, 216 complaints have been filed, 160 of which were submitted by just one woman, Connie Phillips, on behalf of a small group called the St. Tammany Parish Library Accountability Project. St. Tammany Parish Library has rapidly become the site of one of the highest recorded number of book complaints in the country, accounting for 16% of all book complaints filed nationally in 2022.

Many of the complaints submitted by Phillips rely heavily on Book Looks reports. In at least three cases, however, Stacker identified complaints that copied information from a completely unrelated Book Looks report. Phillips’ complaint forms for Theresa Thorn’s “It Feels Good to be Yourself,” shelved in juvenile fiction; Robb Pearlman’s “Pink Is for Boys,” a picture book; and “Tomboy,” which Phillips identified as an audiobook by French Audo, and which wasn’t found in St. Tammany’s collection; all lifted quotes from the Book Looks report for Courtney C. Stevens’ young adult novel “Dress Codes for Small Towns.” (Phillips did not submit a complaint about “Dress Codes.”) The St. Tammany Parish Library Accountability Project did not immediately respond to Stacker’s request for comment.

Despite none of the quotes nor profanity appearing in those three books, the library still has to follow its official review process to respond to the complaints.

St. Tammany Library conservatively estimates that each statement of concern costs about $409 to respond to. That doesn’t include the time it takes for librarians and board of control members to read the books.

Despite these grim figures, LaRocca told Stacker that anti-censorship advocates have always vastly outnumbered those who favor restricting book access at library board meetings.

The Library Accountability Project continues to submit book challenges and has organized beyond board meetings to target the library’s staff and leadership. In a presentation on their website, the group claims librarians are distributing pornography to minors but uses passages from graphic novels shelved in the adult sections of St. Tammany library branches.

In December, tensions arose when two women thought to be affiliated with the project reported library staff members at the Covington branch to police for allegedly distributing pornography to minors. They specifically called out Kobabe’s “Gender Queer,” which has topped banned book lists in recent years. At the branch, the book is shelved in the adult section and was checked out of the library at the time.

When law enforcement arrived, LaRocca said the officer seemed confused and didn’t know why he was there. After talking to the library staff, he left without making any arrests. The library has not heard anything more about the complaint.

The library’s data suggests the Library Accountability Project’s concerns likely represent a vocal minority, as circulation reached nearly 1 million in 2022, a nearly 9% increase from 2021.

“If the community didn’t trust us or wasn’t happy with the materials that we had, then they wouldn’t visit us, and they wouldn’t check them out,” LaRocca said. “We still have a community that’s interested in having a library.”

Emma Rubin // Stacker

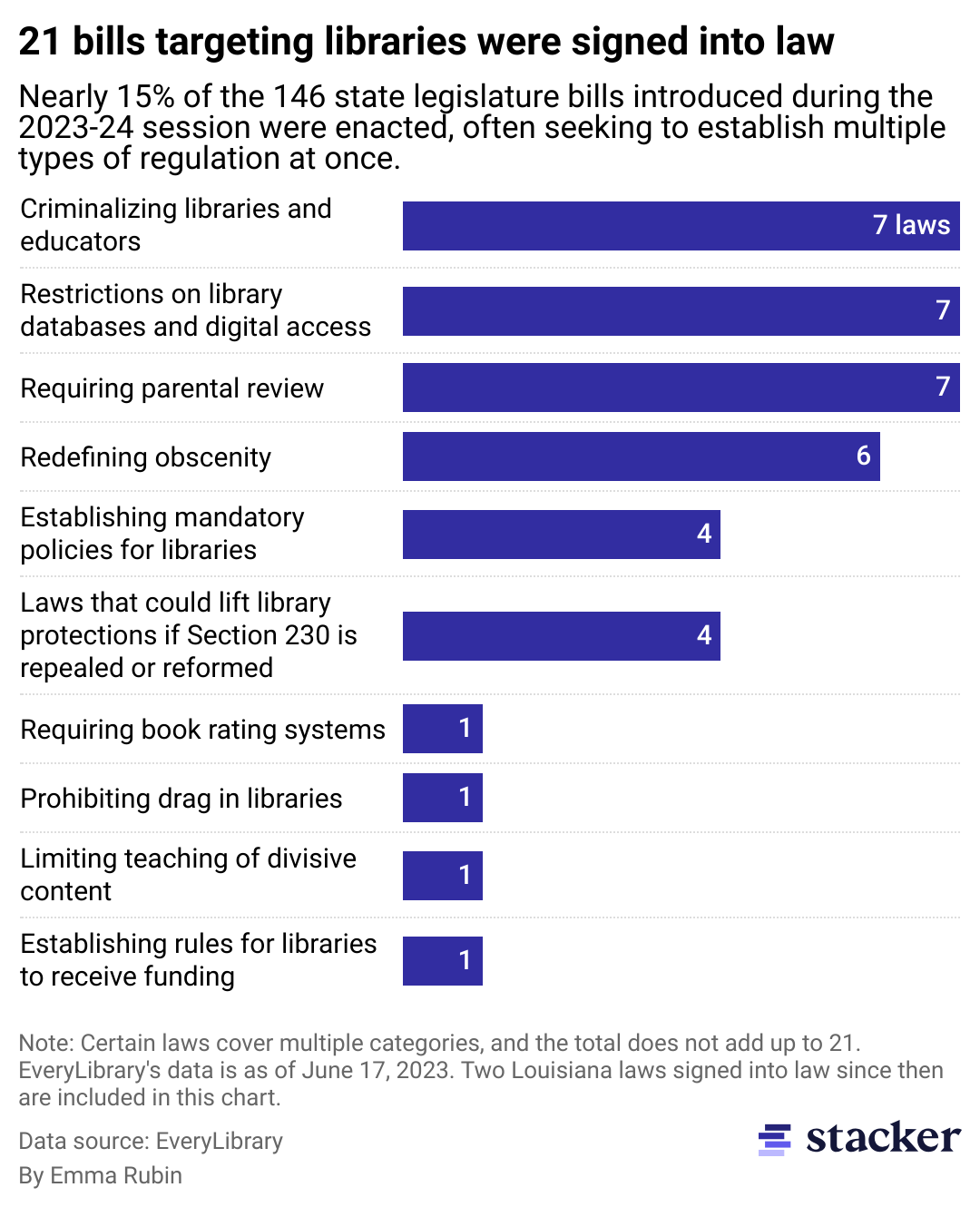

New state laws support attempts to restrict library materials

Several states, including Texas, Florida, South Carolina, and Utah, have introduced official and unofficial measures to make book banning easier.

Some state-level book policies invoke terminology like “pornography” and “obscenity” to restrict materials available to minors while leaving the definitions of these terms vague enough to be widely and indiscriminately applied. Other laws, like those passed in Arkansas and Indiana, target librarians and educators more directly, making them criminally liable for distributing “obscene” materials. Some schools and libraries may preemptively remove materials to comply with newly enacted legislation.

Certain book challenges—like this one submitted to St. Tammany—specifically cite pieces of legislation, highlighting how vague language like “harmful to minors” can be used to support the removal or restriction of materials.

Less official measures from politicians can have a similar effect despite having no legal basis. In 2021, then-Texas state Rep. Matt Krause circulated a letter to school administrations asking them to report whether they owned any of 849 specific books. An analysis of the books by Book Riot noted that nearly two-thirds of the books (62.4%) included on the list contained LGBTQ+ themes.

Though there was no specific legal directive to remove the books, many Texas schools were confused about how to comply. Some schools and parents challenged the books on the list en masse.

There is no official affiliation between the Krause List and books flagged by Book Looks, but certain frequently targeted titles appear on both. At least 1 in 9 of the 849 titles on the Krause List have Book Looks ratings, according to a comparison by Stacker.

In Granbury, Texas, the Krause List was just one factor in a yearslong effort to remove books with LGBTQ+ themes from the local school district—a push that resulted in the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights launching a first-of-its-kind investigation into the school in December 2022.

The campaign to remove LGBTQ+ books from Granbury schools ramped up with the election of several far-right Christian conservatives to the school board. In early 2022, the school’s superintendent, Jeremy Glenn, was recorded pressuring school librarians to remove LGBTQ+ books, telling them that if their beliefs diverged from those of the conservative school board, “You better hide it.”

Glenn and the district published a written statement (that has since been taken down) in response to the leaked recording, noting that they support children from all backgrounds but that “the values of our community will always be reflected in our schools.”

Weeks later, roughly 130 books were removed from Granbury library shelves. Nearly 3 out of 4 books had LGBTQ+ themes or characters, according to ProPublica and Texas Tribune’s analysis. Eventually, three of the books were banned, and most of the rest were returned to the library; but the fight wasn’t over yet.

Tensions escalated when two book review committee members, Karen Lowery and Monica Brown, filed a complaint with the local constable alleging that pornography was being kept in the Granbury school library. Like the incident involving police in St. Tammany Parish, no arrests were made.

According to Adrienne Quinn Martin, an outspoken critic of the Granbury book-banning efforts and the mother of one current and one former Granbury student, national groups like Moms for Liberty haven’t taken root in Hood County because there is already plenty of local mobilization.

“This is already a Christian nationalist county, and it’s being run that way,” Martin told Stacker.

In the absence of Moms for Liberty, there is a Granbury chapter of Rated Books, which uses Book Looks to facilitate book challenges in communities nationwide. It is unclear whether the school board members responsible for campaigning for book bans in the Granbury school district are affiliated with the Granbury Rated Books site. Stacker’s emails to the national Rated Books address listed on the Granbury chapter’s website went unanswered.

Organizations against book banning are pushing back

As quickly and prolifically as groups have emerged to challenge library materials over the last several years, organizations devoted to fighting book bans have sprung up to counter them.

Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship, a coalition of local groups, was founded in late 2022 after the conservative Lafayette Public Library board canceled the library’s Pride Month displays and attempted to fire a librarian who acted against the measure. The board also gave itself the power to decide which challenged books would be removed from the shelves, a decision usually made by librarians.

Lynette Mejía, a co-founder of Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship and a Lafayette resident, told Stacker that she and others felt their local library was under attack. Mejía, along with fellow co-founders Amanda Jones and Melanie Brevis, were spurred into action when they heard about incoming state legislation limiting access to library materials. They feared what had happened at Lafayette would soon spread to other Louisiana parishes.

Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship provides resources for starting local freedom-to-read groups, connects existing organizations across the state with one another, and keeps people updated on book-banning efforts in Louisiana.

So far, efforts by groups like the St. Tammany Parish Library Accountability Project and a similar organization, Citizens for a New Louisiana, have had a hard time gaining a real foothold in Louisiana libraries apart from Lafayette, according to Mejía.

That’s because many people have shown up to board meetings in support of keeping library materials accessible. “People respond to people who live [in their community] and have a stake in their local library,” Mejía said.

Paying close attention to what’s happening at the hyperlocal level and being ready to jump into action are key parts of staving off book ban attempts, according to advocates.

“As soon as this starts happening in your community, you need to organize and fight against it because it does not take long for that match to set fire to your whole town,” Martin said. “They have a playbook. They follow it. It works.”

Larger-scale efforts to stave off organized book challenges are also underway. National organizations like the ACLU, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and the Freedom to Read Foundation provide legal resources and aid to people fighting book bans. Students have also mobilized to support book access by forming “banned-book clubs,” participating in protests, and getting involved in national initiatives.

“This is going to be a long road to take back our libraries and to recover what we’ve lost,” Mejía said. When she gets tired, she reminds herself that “growing up with access to [public libraries] is such an important part of living in a free society, and it’s worth fighting for, no matter how long it takes.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.