A timeline of the Vietnam War

Published 1:00 pm Wednesday, October 25, 2023

A timeline of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War, officially stretching from Nov. 1, 1955-April 30, 1975, was a conflict with profound international implications that changed the landscape of American international policy for decades to come—a phenomenon called Vietnam syndrome.

On a human level, the war was disastrous—an estimated 2 million Vietnamese civilians were killed, and over 1 million Vietnamese soldiers lost their lives. Over 2.7 million Americans served in the war, and 58,318 died, with thousands more suffering from the lifelong impacts of post-traumatic stress disorder, a poorly understood affliction at the time.

Stacker compiled a timeline of the Vietnam War using various news and government sources to give a sense of the conflict’s scope and unfolding. The lead-up to the war begins with Vietnam’s colonial history.

Napoleon III, France’s first president, began an invasion process of Vietnam in 1858, concluding in 1883 with a complete annexation of the country. By 1893, France annexed neighboring Cambodia and Laos as well and created out of the three nations a territory referred to as Indochina.

Life in Vietnam under French colonial rule was brutal, with Vietnamese people granted few civil liberties and subjected to constant exploitation. A clear indicator of colonialism’s long-term and devastating impact, most of the population was literate in Vietnam—a state that existed for centuries before the French invasion—before French colonial rule. By 1939, 80% of the population was illiterate, and 45% of the land was owned by 3% of landowners, while half of Vietnam’s population was landless.

Though there had been uprisings predating him, the emergence of Hồ Chí Minh into Vietnam’s political arena in the 1930s marked the beginning of a new period of resistance for Vietnam. Internationally educated, Hồ introduced communism to the nation as a clear political antithesis to France’s capitalistic, colonial rule.

During World War II, with the fall of France to Nazi Germany, Vietnam became a possession of Japan, though the French Vichy government still administered it. Once Japan surrendered, Hồ Chí Minh and the Viet Minh successfully led Vietnam to independence, forming the short-lived Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

However, post-war France was vehement in its aims to reestablish a French empire, with Charles de Gaulle proclaiming that if the U.S. did not back France in its reconquest of Vietnam, they might ally themselves with Soviet Russians. Thus began the First Indochina War, a conflict that would eventually morph and spiral into the Vietnam War.

Of the many precipitating events that followed, few were as pivotal as the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in setting the stage for the outbreak of the Vietnam War. A crushing defeat of French forces by the Viet Minh occurred in the lead-up to peace negotiations in Geneva.

The battle resulted in the deaths of 2,200 French soldiers and the capture of almost 11,000. The defeat escalated negative public opinion of France’s presence in Vietnam, led to the partition of the country, and the eventual complete withdrawal of French presence—to be replaced eventually by American intervention.

![]()

Bettmann // Getty Images

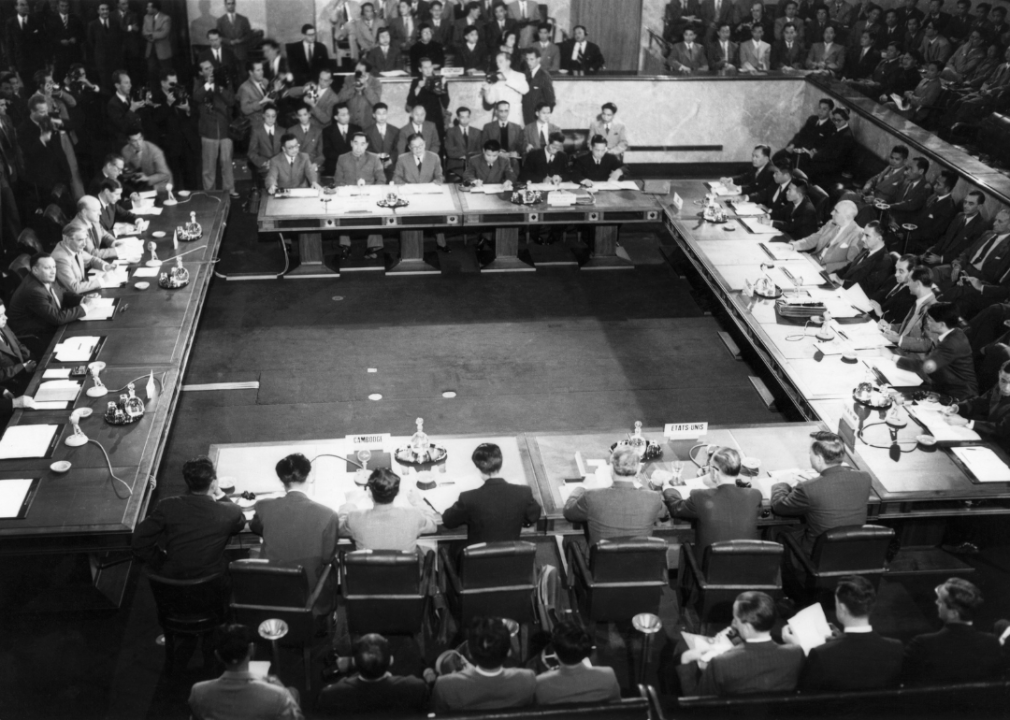

July 1954: International conference in Geneva splits Vietnam in two

On the heels of the end of the Korean War (which saw Korea divided at the 38th parallel), negotiators at Geneva proposed a partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. Hồ Chí Minh, Vietnam’s leader, faced pressure from his Soviet and Chinese allies to accept the terms of the settlement, as their political aim at that moment was to minimize conflict with Western nations.

Keystone-France // Getty Images

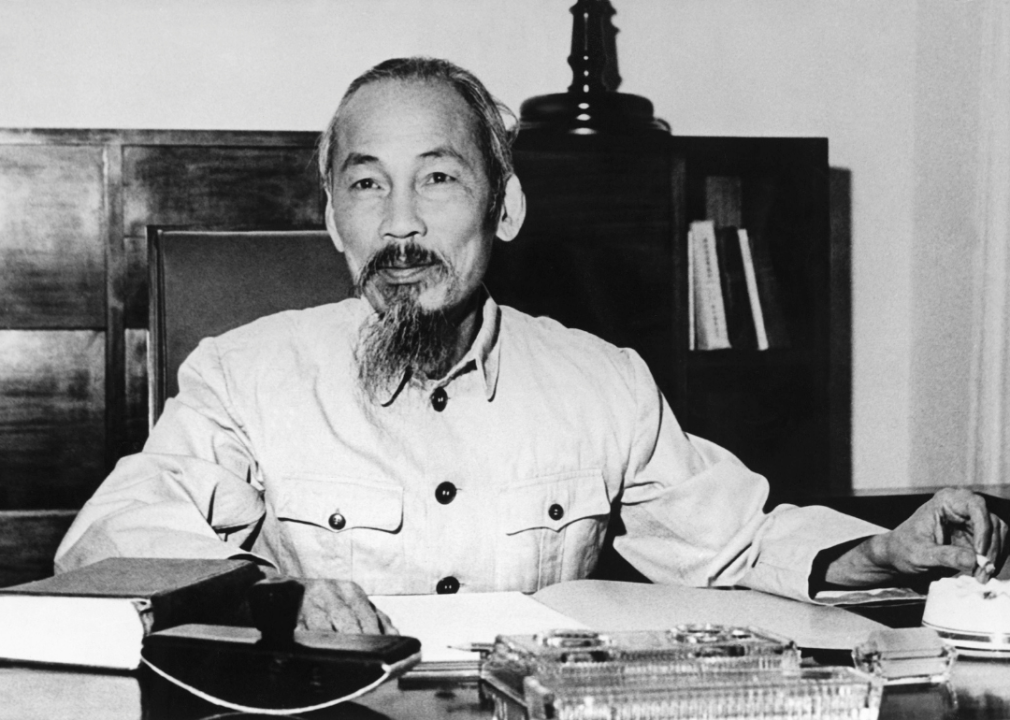

1955: North Vietnam becomes a communist state while a US-backed Catholic nationalist leads South Vietnam

Intended as a temporary division, the Geneva Accords stipulated a general election was to be held two years later that would reunify the nation. In part, as a result of the U.S.-backed rise of Catholic nationalist Ngô Đình Diệm in South Vietnam, these elections were never held, and with Hồ Chí Minh (pictured here) leading North Vietnam as a communist state, the two states moved toward conflict.

Keystone // Getty Images

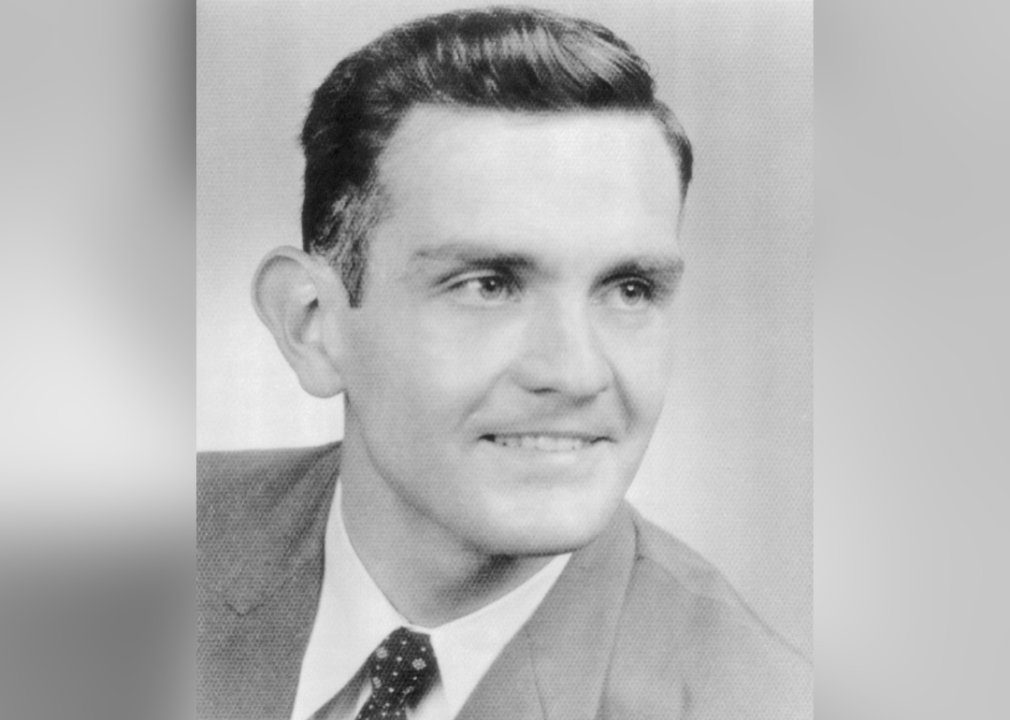

1957: Ngo Dinh Diem leads South Vietnam

South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm staffed the top roles of his authoritarian government with his own family members. The autocrat is pictured here on March 7, 1957, at a fair near Saigon shortly after an attempt on his life was foiled. He was assassinated six years later, on Nov. 2, 1963, in a CIA-backed coup.

Bettmann // Getty Images

May 1959: North Vietnam begins building the Ho Chi Minh Trail to transport supplies

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was used to ferry supplies and soldiers to South Vietnam. It snaked through the mountains and jungles of neighboring Cambodia and Laos, and it often took more than one month to traverse. Part of the North’s guerrilla and revolutionary warfare strategy, the trail remained an important and continually growing pathway from North to South.

Sovfoto // Getty Images

September 1960: Ho Chi Minh gives up his party position and Le Duan rises to power in North Vietnam

During the third congress of the Lao Dong, Hồ Chí Minh ceded his position as party secretary-general to Lê Duẩn. Ho remained North Vietnam’s chief of state and continued to exert influence on the state’s government until his death in 1969, but operated largely behind the scenes. Lê Duẩn was a prominent and influential figure throughout Vietnam’s early 20th-century history, and he is generally considered to have had a more militaristic approach than Hồ Chí Minh.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

December 1960: National Liberation Front forms

Under the leadership of Lê Duẩn, North Vietnam began to pursue an aggressive war of reunification with the South, beginning with more active support of revolutionary groups in the South. This resulted in the formation of the National Liberation Front, which had the explicit goal of overthrowing the government of Ngô Đình Diệm in the South.

Pejoratively labeled the Viet Cong by the U.S. and the government in Saigon (for Communist traitors to the Vietnamese nation), the NLF differed from its predecessor, the Viet Minh, in that it was not directly tied to a provisional government until nearly a decade later.

Underwood Archives // Getty Images

May 1961: US sends soldiers, helicopters to South Vietnam

Seeing the conflict primarily through a Cold War lens, President John F. Kennedy authorized covert operations in South Vietnam intended to prevent a Communist takeover in the region. The memorandum (NSAM 52) enabled “military, political, economic, psychological” actions to be taken in the region—which included helicopters and 400 Green Beret troops.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

January 1962: Operation Ranch Hand employs the widespread use of Agent Orange

This operation marked the beginning of the use of chemical warfare by the U.S. in Vietnam, known most infamously as Agent Orange. Intended initially to defoliate vegetation and expose hidden trails used by the NLF, between 1962 and 1971, the U.S. dumped approximately 19 million gallons of defoliating herbicides over an area constituting an estimated 10%-20% of Vietnam’s landmass.

These chemicals are now understood to increase the likelihood of a whole host of life-threatening illnesses.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

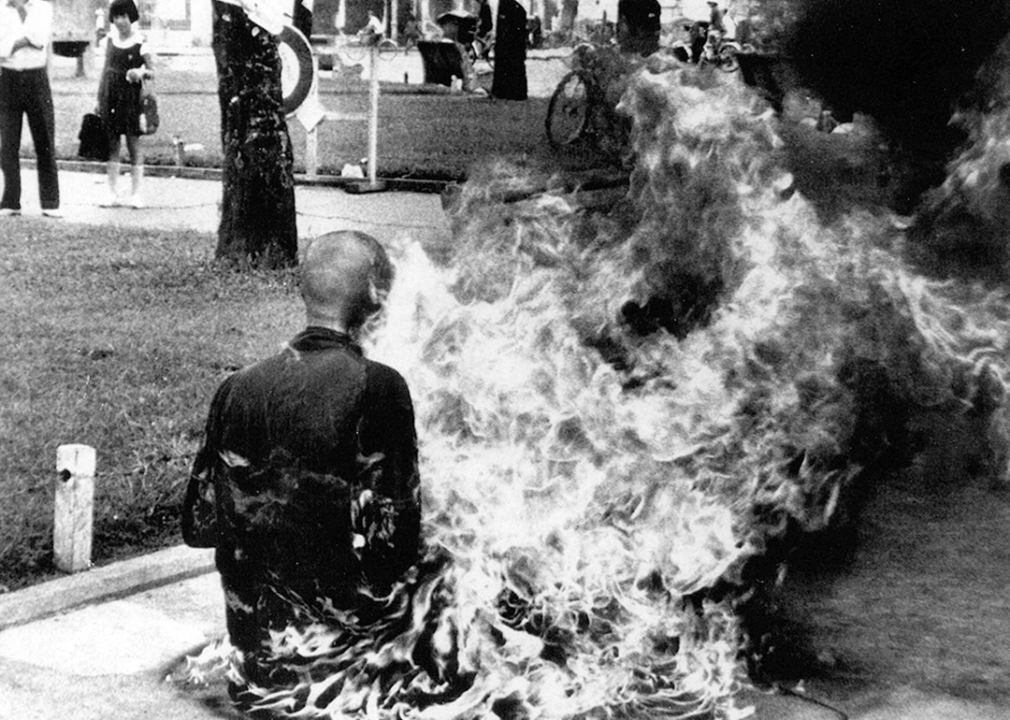

1963: Self-immolation by Buddhist monks

A staunch Catholic nationalist, Ngô Đình Diệm’s rule over South Vietnam gave rise to violent religious oppression, including the deadly suppression of protesting Buddhist monks. In late June, as an act of defiance against the Diem government’s oppressive policies, Thích Quảng Đức, a Buddhist monk, self-immolated—the photos from which led President Kennedy to remark that “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.”

This form of protest continued for much of 1963, and its impact on the Diem government labeled it “the Buddhist Crisis.”

Keystone // Getty Images

November 1963: US-backed coup assassinates Diem

In part, as a result of the fallout from the oppressive and violent policies in Diem’s government, the U.S. indicated support for a military-led coup in South Vietnam. Known as “Cable 243,” the communique from President Kennedy’s government to the U.S. ambassador in South Vietnam had an immediate impact—Diệm and his brother Ngô Đình Nhu were assassinated a few months later, leading to 12 successive military coups between 1963 and 1965.

Bettmann // Getty Images

August 1964: Congress passes Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

Three days after the U.S. initiated the shelling of two North Vietnamese islands, North Vietnamese torpedo boats surprised the Maddox and engaged the destroyer in direct combat. In this photo, President Lyndon B. Johnson confers with the National Security Council following the North Vietnamese torpedo boat attack on the USS Destroyer Maddox.

The Johnson administration used this and a supposed conflict the following day to ensure passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave President Johnson the legal power to wage all-out war in Southeast Asia. Declassified documents have subsequently indicated that the Johnson Administration lied about the events precipitating the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution—namely, that a second and more coordinated attack on both the Maddox and the Turner Joy had not actually occurred.

By this point, there were already 23,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam and approximately 400 U.S. casualties.

PhotoQuest // Getty Images

November 1964: North Vietnam receives more support from USSR, China

In the form of a wide variety of armaments, as well as food and medical supplies, the Soviets increased their support of North Vietnam. China supplied primarily infrastructural support, sending engineering troops to build defense infrastructure. Then, two days before the U.S. election, four Americans were killed in an NLF shelling of Bien Hoa Air Base (pictured here), with 76 more wounded and five B-57 bombers destroyed.

PhotoQuest // Getty Images

February-March 1965: Air Force strikes

The initiation of Operation Flaming Dart marked the first series of U.S. Air Force strikes against North Vietnamese targets. Then, in a bid to challenge the NLF’s supply lines, President Johnson launched Operation Rolling Thunder.

Three years of continual bombing of North Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail resulted in an estimated 182,000 Vietnamese civilian deaths. Finally, in March, the U.S. landed its first major deployment of ground troops at Da Nang—with the intended purpose of defending U.S. air bases.

Bettmann // Getty Images

March 1965: Marines arrive at Da Nang by sea

In the first deployment of a major American ground combat unit to Vietnam, Marines began arriving by landing craft at Da Nang on March 8, 1965. The objective was to defend the Da Nang air base, but inched the U.S. another step away from an advisory capacity and a step closer to direct war participation. Nearly 5,000 Marines—including supply and logistics units, two infantry battalions, and two helicopter squadrons—had arrived at Da Nang by month’s end.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

August 1965: Operation Starlite marks first major US ground offensive in Vietnam

Marking a turning point in the U.S. Marines’ primary mission from one of defense toward aggressive action, 5,500 U.S. Marines conducted an assault on the 1st NLF Regiment. It was an early success for U.S. military forces in the Vietnam War—with 614 NLF troops killed, 45 U.S. Marines killed, and 203 wounded. Lasting six days, Operation Starlite largely scattered the 1st NLF Regiment, though it would regroup and rebuild later.

Bettmann // Getty Images

November 1965: Norman Morrison sets himself on fire in front of Pentagon to protest the Vietnam War

Substantial antiwar protests began in the U.S. as early as 1963—but a turning point definitively arrived after the self-immolation of Norman Morrison. Staging his protest in front of the Pentagon, Morrison was a Quaker and pacifist from Baltimore, and though his actions did not lead to any direct changes in policy from the U.S. government, he was lauded in Vietnam for his sacrifice.

Bettmann // Getty Images

November 1965: The Battle of Ia Drang

The Battle of Ia Drang Valley pivoted the war from one primarily of small conflicts to full-fledged assaults. The battle had long-lasting implications, in that it reinforced tactics for both armies—with the NLF relying upon close-quarter combat to reduce artillery efficacy, and the U.S. pursuing a war of attrition with North Vietnam, aiming to dwindle their numbers. The casualties of this battle greatly vary depending on the source, but estimates suggest hundreds of Americans and thousands of North Vietnamese died.

In this photo, President Johnson awards the Presidential Unit Citation to the First Cavalry Division for heroism in the Ia Drang Valley in Vietnam from Oct. 23 to Nov. 26, 1965.

– // Getty Images

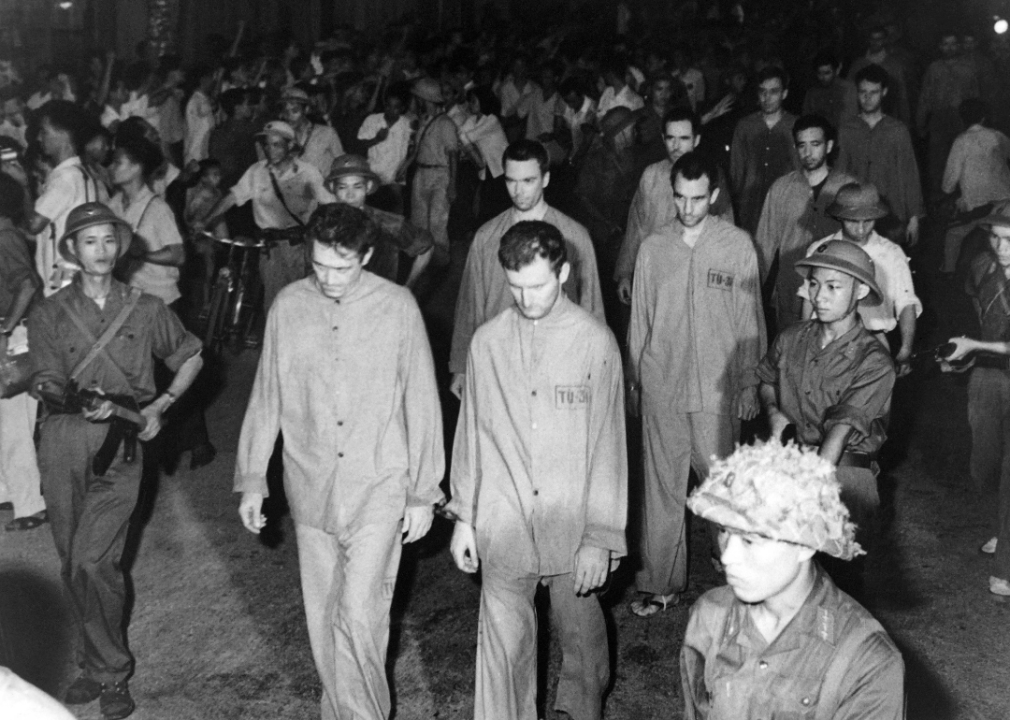

1966: Number of US troops in Vietnam rises to 400,000

After a year of tremendous upscaling in the U.S. war effort in Vietnam, by year’s end, 6,000 American and 61,000 North Vietnamese soldiers had been killed, with 30,000 more American soldiers wounded. Domestically, the number and frequency of antiwar protests rose in the U.S. while reporting on the abusive treatment of U.S. prisoners of war (pictured here) by North Vietnam gathered attention to the conditions of life for POWs.

Patrick Christain // Getty Images

February 1967-January 1968: Operation Pershing

Operation Pershing was an 11-month, cooperative military campaign to scale back communist forces and compromise their infrastructure. The effort was led by the First Cavalry Division and included the Third Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam 22nd Division, and the South Korean Capital Division in Binh Dinh Province.

In this photo, the second wave of combat helicopters of the First Cavalry Division flies over a radio telephone operator and his commander on an isolated landing zone during Operation Pershing.

Ernst Haas // Getty Images

April 1967: Massive antiwar protests

With nearly 40,000 young men being drafted every month, disillusionment spreading in particular through universities, and news of battlefield casualties reaching the American population, antiwar protests began to gain in size.

The April protests garnered the participation of hundreds of thousands across multiple U.S. cities, with a number of prominent public figures attending, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. On Oct. 21, 100,000 protesters gathered at the Lincoln Memorial, with an estimated 30,000-50,000 continuing the march and protesting at the Pentagon.

Bettmann // Getty Images

September 1967: Nguyen Van Thieu becomes president of South Vietnam

Having fought against the Viet Minh with the French in 1945, and taking part in the coup against Ngô Đình Diệm in 1963, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu led South Vietnam for the remainder of the war. A staunch anti-communist, he retained American political backing until its eventual withdrawal from the conflict and was famously uncompromising with his North Vietnamese rivals.

FRANCOIS MAZURE/AFP via Getty Images

November 1967: Battle of Dak To

American soldiers are pictured here launching rockets on Nov. 21, 1967, during the battle of Dak To. Comprising the battle was a series of engagements between Nov. 3-23 of that year in Kon Tum Province. The Americans and South Vietnamese were successful in driving the North Vietnamese from the Kontum Province, but it was a costly battle with 376 U.S. people killed or listed as missing or presumed dead; another 1,441 were wounded.

Dick Swanson // Getty Images

Early 1968: Marines in prayer

With the Tet Offensive showing in stark terms that a conclusion to the Vietnam War was nowhere in sight, antiwar protests on American soil peaked in early 1968. For those deployed, morale dipped—a trend that continued well into the 1970s. Here, Chaplain Ray Stubbe leads a group of Marines in prayer near their sandbagged position along the perimeter of a base in Khe Sanh, Vietnam, in March of 1968.

– // Getty Images

January 1968: Tet Offensive begins

A series of widespread and coordinated assaults on South Vietnamese cities by North Vietnam and the NLF, the Tet Offensive was a turning point in the war, marking an end to the American narrative that the war would wrap up quickly.

North Vietnam and the NLF suffered massive casualties from the offensive, with an estimated 50,000-60,000 dead. And while the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces suffered a comparatively slight death toll (with 2,100 and 4,000 dead, respectively), the offensive nevertheless exacerbated worsening domestic opinion of the war in America.

Terry Fincher/Express // Getty Images

Feb. 19, 1968: Vietnamese refugees

Many Vietnamese refugees fled during the Battle of Hue, a major military engagement in the Tet Offensive, that lasted from Jan. 31-March 2, 1968. Some of those fleeing stopped to help South Vietnamese soldiers rebuild damaged or destroyed bridges like the one pictured, which connected banks along the Perfume (Hương) River, so refugees could make their way across.

Bettmann // Getty Images

March 16, 1968: US troops murder an estimated 500 civilians at the My Lai Massacre

In an unprovoked assault on the village of My Lai in northern South Vietnam, a company of recently deployed and undertrained U.S. soldiers committed numerous atrocities, including the indiscriminate murder of an estimated 500 civilians, including children.

Lieut. William Calley, the leader of the company’s 1st Platoon who personally ordered the mass executions of at least 150 civilians grouped in an irrigation ditch, would later become the only soldier convicted for the atrocity. Though initially sentenced to life in prison for the murder of 22 civilians, he served only 3.5 years, mostly under house arrest, and was released in 1974.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

March 1968: President Johnson halts some bombing of Vietnam in the face of public backlash

Facing backlash on the heels of the massacre at My Lai and million-strong protests of the war, President Johnson slowed the pace of U.S. bombing in Vietnam—calling for peace negotiations—and announced that he would not run for reelection. Richard Nixon would go on to win the subsequent presidential election, promising to end U.S. involvement in the war with “peace and honor.”

Bettmann // Getty Images

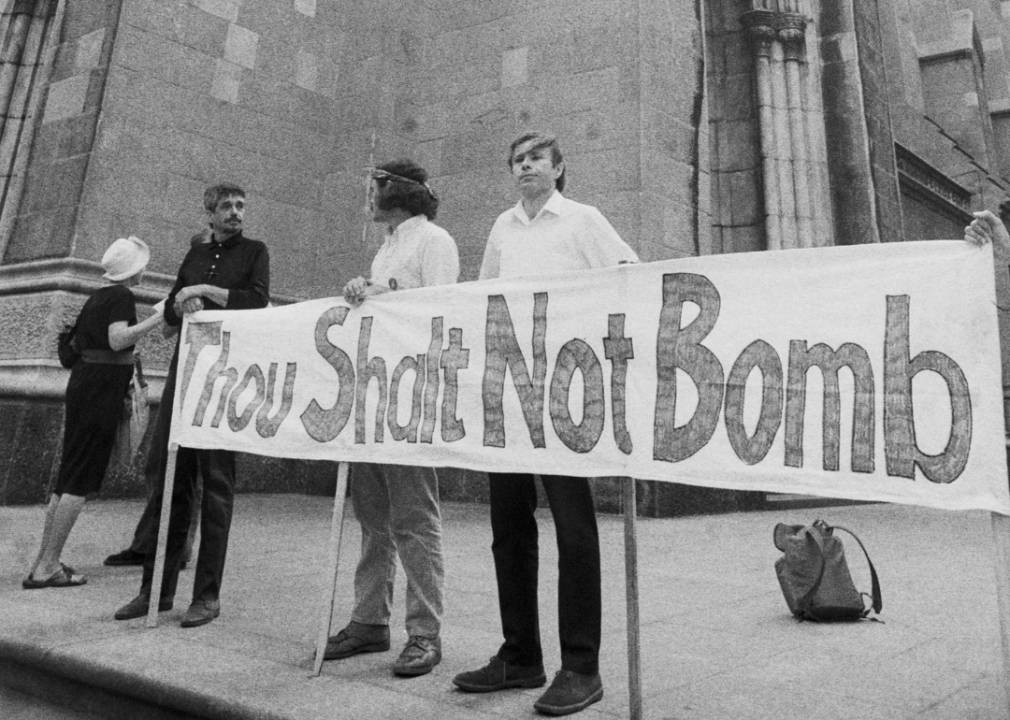

March 1969-May 1970: Operation Menu

Beginning in 1969 and taking place over four years, the U.S. bombing of Cambodia is estimated to have killed 150,000-500,000 civilians. Intended to combat the growth of communism in the country, President Nixon attempted to keep the existence of these raids secret from Congress and the American public, but word got out and resulted in widespread protests.

Photographed here are the Rev. Daniel Berrigan and others standing behind a “Thou Shalt Not Bomb” sign at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City in protest of U.S. bombings in Cambodia.

Bettmann // Getty Images

May 1969: Hamburger Hill

American and South Vietnamese troops spent 10 days in May 1969 locked in battle over control of what became known as Hamburger Hill, a 3,074-foot hill in a far-flung valley in South Vietnam. The effort was part of Operation Apache Snow, undertaken to remove enemy forces in the A Shau Valley and prevent PAVN units from launching attacks on nearby coastal provinces.

The U.S. military captured the hill following a series of assaults that resulted in 72 dead Americans and 372 wounded, only to abandon it days later. In this photo, 101st Airborne Division troopers are seen on Hamburger Hill during the controversial conflict.

– // Getty Images

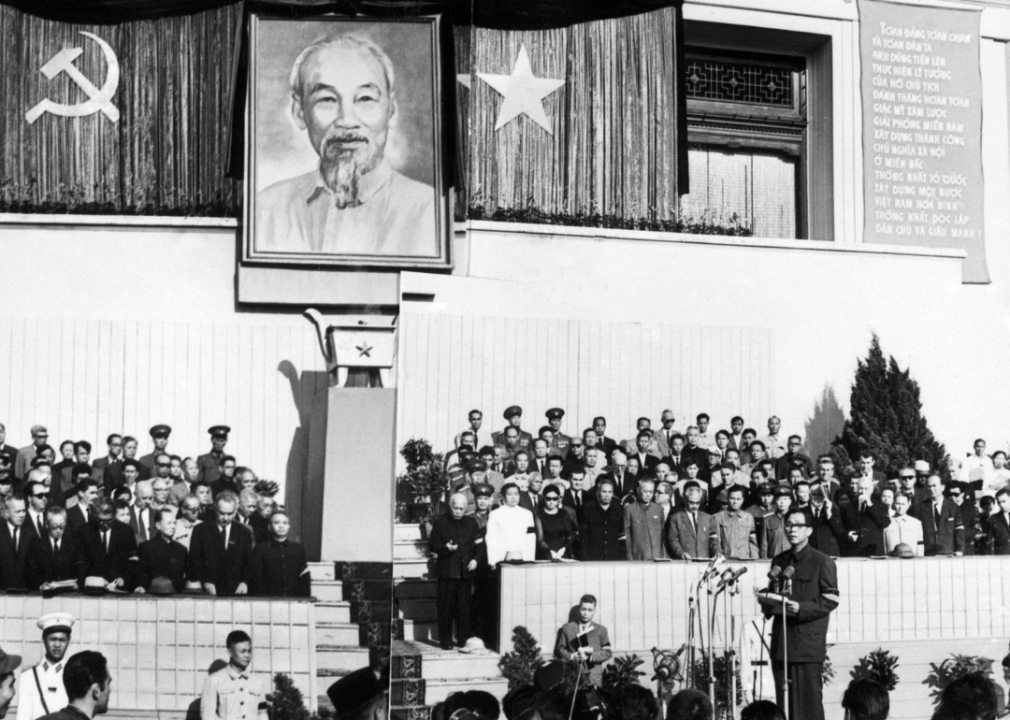

September 1969: Ho Chi Minh dies of a heart attack

After an extended period of ill health, Hồ Chí Minh died of heart failure at his home in Hanoi. Control of North Vietnam had long been ceded to his successors by this point, but Hồ remained involved in North Vietnamese affairs and was a deeply symbolic figure for many Vietnamese. His funeral was attended by 250,000 mourners, including the Soviet premier and the Chinese vice-premier.

The Sydney Morning Herald // Getty Images

December 1969: US begins first draft lottery since World War II

The draft lottery system worked by randomly assigning every potential birthdate in a year a number between 1 and 366, determining the order in which people would be called to serve based on their day of birth. The date Sept. 14 was assigned the number 001—and all in all, only numbers 1 through 195 were called to duty. America suspended the use of the involuntary draft in 1973, relying on voluntary enlistment from then on.

Consolidated News Pictures // Getty Images

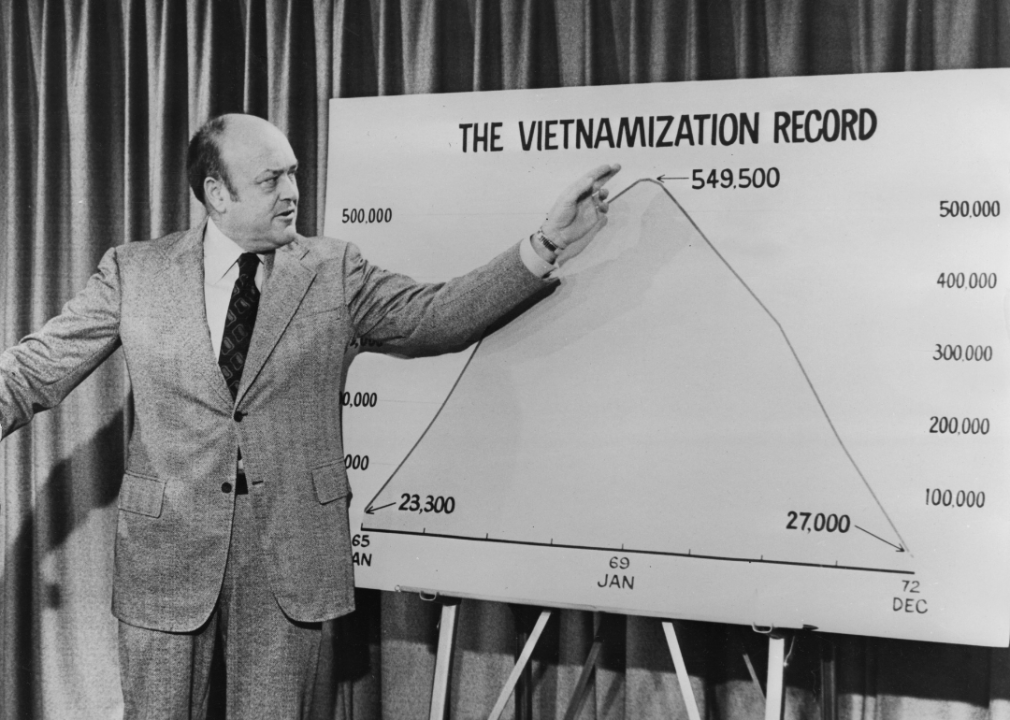

1969-1972: US gradually pulls troops out of Vietnam

From 1969 to 1972, the U.S. pulled out hundreds of thousands of troops from Vietnam: a process of gradual shifting of responsibility to the South Vietnam government known as Vietnamization. By the end of 1972, only 24,200 U.S. troops remained in Vietnam, having peaked at 536,100 in 1968. South Vietnam had amassed nearly 1 million soldiers in its army by this point.

Bettmann // Getty Images

February 1970: Secret peace negotiations

Beginning in 1969 and 1970 and lasting until 1973, U.S. National Security Advisor (and later Secretary of State) Henry Kissinger (at left) conducted negotiations throughout 68 meetings with Le Duc Tho (at right), a member of North Vietnam’s politburo.

These talks would eventually lead to the Paris Peace Accords in 1973—even as Kissinger was directly involved with war escalations. Jointly receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts, Le Duc Tho refused the award, and Kissinger later offered to return it after South Vietnam fell in 1975.

Spencer Grant // Getty Images

May 4, 1970: National Guardsmen open fire on antiwar protesters at Kent State

One of the most infamous domestic events of the Vietnam War, the protests at Kent State had arisen as news of the secret raids in Cambodia spread. The Ohio National Guard killed four unarmed college students and wounded nine more during the shooting. In the aftermath, President Nixon withdrew troops from Cambodia but did not discontinue the deadly and indiscriminate bombing campaign.

This photo shows the large crowd that gathered in front of the State House at Boston Common to protest the Kent State University Shooting.

MPI // Getty Images

June 1970: Congress repeals the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

In an attempt by Congress to limit presidential power over the Vietnam War effort, the repeal of the Tonkin Resolution passed in the Senate 81-10. The Nixon Administration would argue that it did not derive its legal authority in conducting the Vietnam War from the Tonkin Resolution but that the president already had the authority as commander in chief.

Christopher Jensen // Getty Images

January-March 1971: Operation Lam Son fails to cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail

Advancing into Laos to stem the flow of soldiers and supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, three South Vietnamese divisions marched into a trap laid by North Vietnamese forces. In part a test of Vietnamization, U.S. troops were not permitted to cross into Laos, though they did provide air support. The ensuing conflict lasted 60 days and ended in failure—resulting in 9,000 South Vietnamese casualties, the destruction of a vast quantity of South Vietnam’s armored vehicles, and hundreds of U.S. helicopters and planes.

Bettmann // Getty Images

June 1971: The New York Times publishes the Pentagon Papers

The Pentagon Papers, provided to the New York Times by RAND employee Daniel Ellsberg, contained a full and often classified history of U.S. involvement in Indochina, including details of the lead-up to the Vietnam War that had not been revealed to the American public. The embarrassment of the Pentagon Papers led President Nixon to illegally attempt to discredit Ellsberg, efforts which came to light during the Watergate scandal and resulted in Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

May 22, 1972: War protestors burn draft cards

Draft-card burning stands as one of the most well-known and symbolic forms of protest during the Vietnam War. Here, antiwar demonstrators burn their draft cards on the steps of the Pentagon in Washington D.C.

Bettmann // Getty Images

June 1972: Horrors of war

In this photo, Vietnamese children flee from their homes in the South Vietnamese village of Trang Bang after South Vietnamese planes accidentally dropped a napalm bomb on the village, located 26 miles outside of Saigon. Twenty-five years later, Phan Thi Kim Phuc—the young girl running naked from her village—was named UNESCO goodwill ambassador.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

March-October 1972: North Vietnam launches the Easter Offensive against South Vietnam

Equipped with new weaponry provided by China and Soviet Russia, North Vietnam launched a more conventional, multipronged, and full-scale attack from Laos, Cambodia, and across the demilitarized zone, leading to a gradual South Vietnamese retreat but ultimately repelling North Vietnamese forces. As many as 100,000 North Vietnamese troops were lost in the assault, with South Vietnam casualties numbering roughly 43,000 with 10,000 dead.

Over 25,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed, and an estimated 1 million were displaced as a result of this conflict.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

December 1972: Nixon launches Operation Linebacker

A last and perhaps desperate attempt to materially and psychologically damage the North Vietnamese people through “shock and awe” tactics, Operation Linebacker resulted in the deaths of at least 1,600 Vietnamese civilians in densely populated regions.

Widespread infrastructural destruction set the country back on many of the early improvements the Communist government had undertaken. Thirty-three U.S. airmen were killed in the raids, and 15 B-52s were shot down—deaths that were seen domestically as largely in vain, as historians generally agree that North Vietnam had already decided to resume peace talks before the bombings.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

January 1973: US ends draft lottery, Nixon signs the Paris Peace Accords

The signing of the Paris Peace Accords marked the end of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, with all troops to be withdrawn in 60 days. Under the agreement, Vietnam remained divided into North and South at the 17th parallel—though North Vietnam swiftly resumed planning the takeover of South Vietnam.

Bettmann // Getty Images

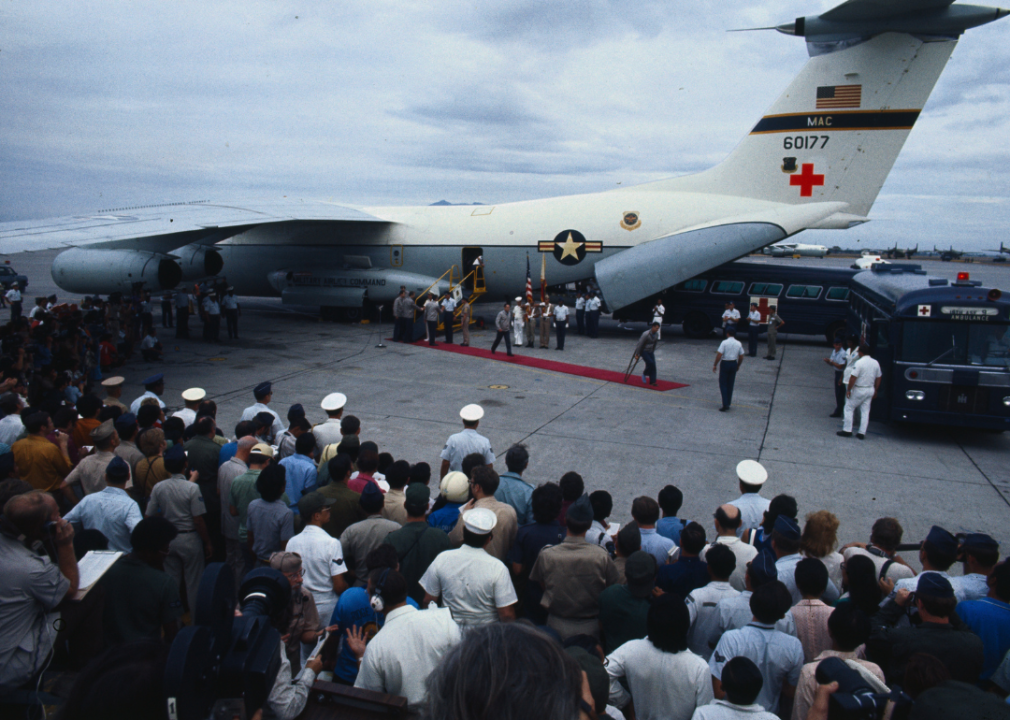

1973: Operation Homecoming

The POWs returned after the Paris Peace Accords arrived from captivity under North Vietnam, the NLF, and other militant groups. Some had been held for as long as five years, and the longest-held U.S. POW for nine—North Vietnam acknowledged that 55 American servicemen had died during captivity. In all, Operation Homecoming saw the return of 591 American prisoners of war from Vietnam.

Bettmann // Getty Images

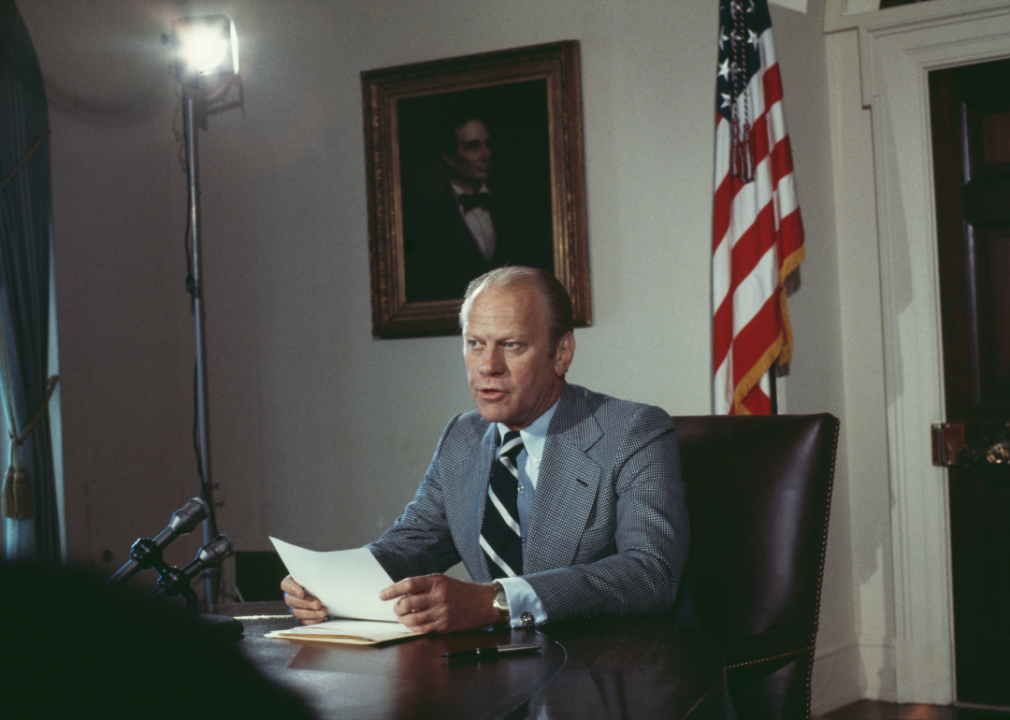

January 1975: President Ford says US will have no further involvement in Vietnam

After the North Vietnamese blatantly broke the Paris Peace Accords, President Gerald Ford declared that the U.S. would commit no further resources or troops to Vietnam. The news deeply dismayed the South Vietnamese government, which struggled to maintain a grip on its territory. In the subsequent March, the North Vietnamese began a massive offensive that would result in the full-scale retreat and ultimate defeat of South Vietnamese forces.

David Hume Kennerly // Getty Images

April 1975: US transports more than 1,000 American troops and 7,000 South Vietnamese refugees out of Saigon as South Vietnam surrenders to Communist forces

After only five weeks, the North Vietnamese army made widespread and rapid gains, quickly advancing to Saigon and encircling the city. As the U.S. embassy and the troops guarding it were being evacuated, two U.S. Marines died from a rocket attack, the final U.S. casualties of the war. South Vietnam offered an unconditional surrender, potentially preventing a bloody urban conflict.

Pictures from History // Getty Images

July 1975: North, South Vietnam are officially united under the Communist rule of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

Commemorated thereafter in Vietnam as “Reunification Day,” the country’s reunification also resulted in the renaming of Saigon to Ho Chi Minh City. The government instituted reeducation and relocation policies for former South Vietnamese citizens in the ensuing years.

The end of the war also began a refugee crisis that would last for decades—from 1975 to 1995, more than 3 million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians fled their homelands, often in small vessels, gaining the name of “boat people.”

Additional writing by Nicole Caldwell.

Editor’s note: While every effort was made to confirm the number of involvement and casualties throughout the Vietnam War, exact numbers vary among sources.