Native teens are facing a mental health crisis—here's what's behind the numbers

Published 5:00 pm Monday, January 29, 2024

Native teens are facing a mental health crisis—here’s what’s behind the numbers

Between the historical trauma of the genocide and mass relocations experienced by their ancestors and the current trauma of ongoing discrimination, American Indian and Alaska Native people have suffered systemic harm. Currently, Indigenous teenagers are facing a mental health crisis that is worsening despite federal efforts.

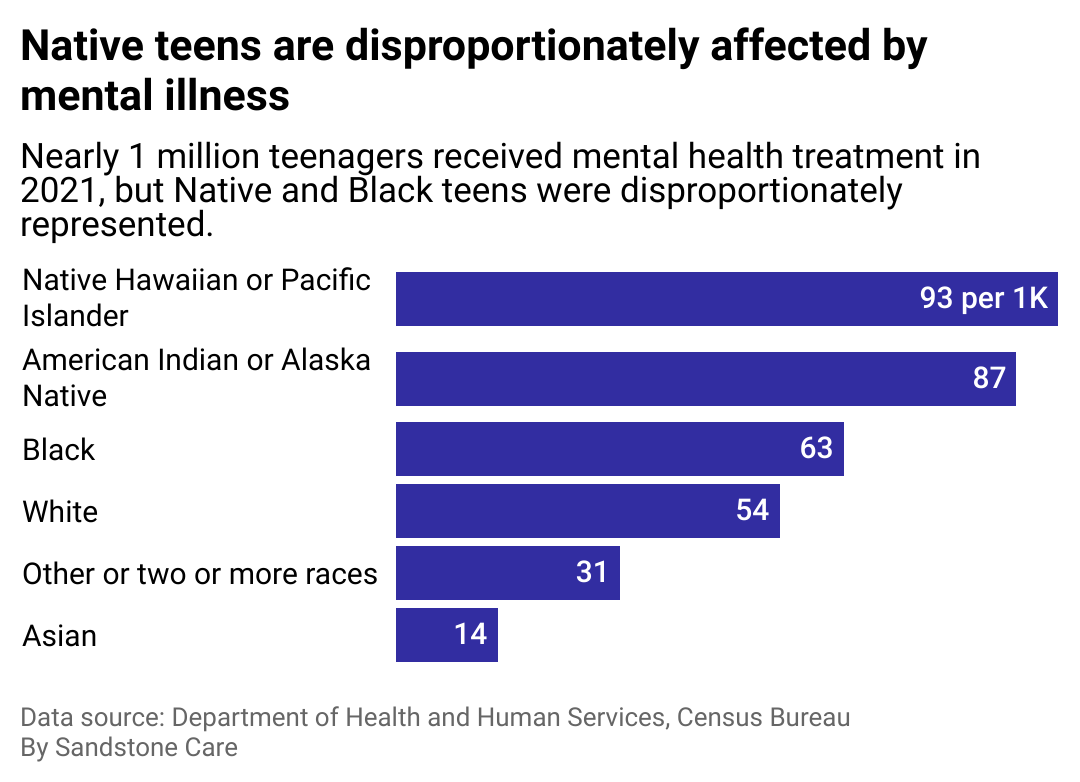

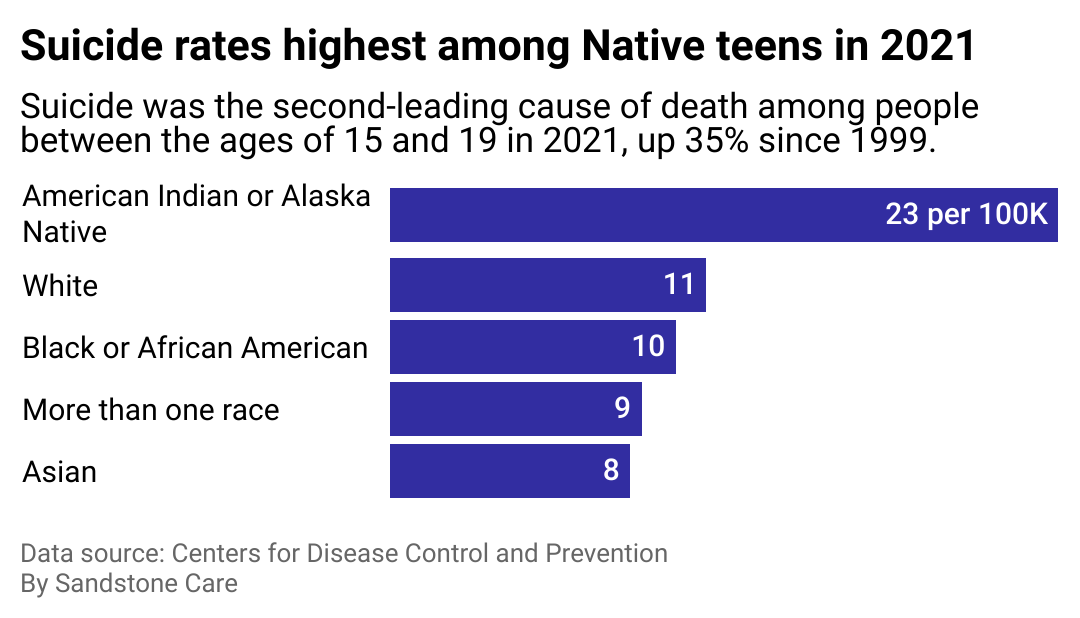

American Indian and Alaska Native teens are more than twice as likely to be receiving mental health treatment than their peers, according to data compiled in 2021 and released last year by the Department of Health and Human Services. They are also at greater risk for suicide, which is among the leading causes of death for Native children between the ages of 10 and 19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sandstone Care analyzed data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other government sources to find out why Native American and Alaska Native teens disproportionately suffer from health disparities, particularly mental illness.

As a whole, Native Americans have faced health disparities since European settlers arrived 500 years ago, beginning with the smallpox epidemic. Historians estimate up to 90% of Native Americans died of smallpox and other infectious diseases between the 16th and 19th centuries. As of 2020, 9.7 million American Indians and Alaska Natives live in the United States, according to the latest Census. That number has nearly doubled in the last 20 years. However, researchers mostly attribute this to more accurate and inclusive counts.

In addition to the physical toll, colonists and later the federal government made active efforts to break up tribes, including separating children from their families. Until as recently as the 1970s, the United States established and supported Indian boarding schools that aimed to “Americanize” Native children, essentially stripping them of their cultural identity.

In recent years, some have attempted to mend these disparities and wrongdoings. In 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland became the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet member. Later that year, she formally recognized the operation of federal boarding schools for the first time. In 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act, which protects Native children from being forcibly removed from their homes by public and private agencies.

Still, the impacts of this historical trauma are pervasive—and have only begun being measured—but include PTSD, substance abuse, and cycles of violence. Intergenerational trauma, which can pass on through DNA, also plays a role. Native teen girls are especially affected, as they are more likely to experience violence in their lifetimes.

Editor’s note: Data on American Indian and Alaska Native people as a group has historically been hard to collect and measure—largely because it’s such a diverse population. Today, there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. Each has unique traditions and languages, is self-governed, and has a distinct community infrastructure.

![]()

Sandstone Care

Native American and Alaska Native youth at risk

Native Americans still face discrimination today, including in the medical setting. They are also less likely to have health insurance or access to care, which further drives inequality and leads to underdiagnosis. For this reason, the true mental toll is difficult to quantify.

Because there is a general distrust of government institutions and the education system overall, Native American teens are more likely than their peers to drop out of high school. However, of the more than 220,000 Indigenous teens enrolled in U.S. high schools in 2021, 8.7% were receiving mental health care at a state-monitored facility, according to the most recent SAMHSA data, compared to 5.5% of all high school students.

American Indians and Alaska Native people between the ages of 15 and 25 have higher rates of economic insecurity, violence, and victimization. Physical health disparities, including obesity and diabetes, can also impact mental health. Suicidal ideation is also more common among this group, with at least 27% percent reporting they seriously considered suicide in a given year, compared to 22% overall.

Sandstone Care

What’s being done to prevent suicide in tribal communities

Suicide is preventable with adequate care.

In 2021, the suicide rate for American Indian and Alaska Native people was two times greater than the general population, according to CDC data. Most were teens and young adults.

To reduce inequities, the CDC recommends improving access to culturally relevant care, including investing in telehealth, training and hiring American Indian and Alaska Native health care providers, and promoting community engagement.

Currently, the federal government works with tribal organizations and other groups to help fund programs to recognize suicide risk within the community and promote prevention programs such as the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Sandstone Care and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.