Nurses battling burnout are choosing less stressful work environments

Published 4:00 pm Monday, July 29, 2024

Nurses battling burnout are choosing less stressful work environments

After years of burnout, many health care professionals are switching jobs or leaving the field entirely as industry challenges and difficult working conditions persist.

Health care workers are no strangers to workplace stress. High patient-to-nurse ratios, low pay, and workplace safety concerns have long been typical challenges faced by nurses and other health care providers. It comes as no surprise that health care professions make up about half of the 2024 U.S. News and World Report’s 20 most stressful jobs.

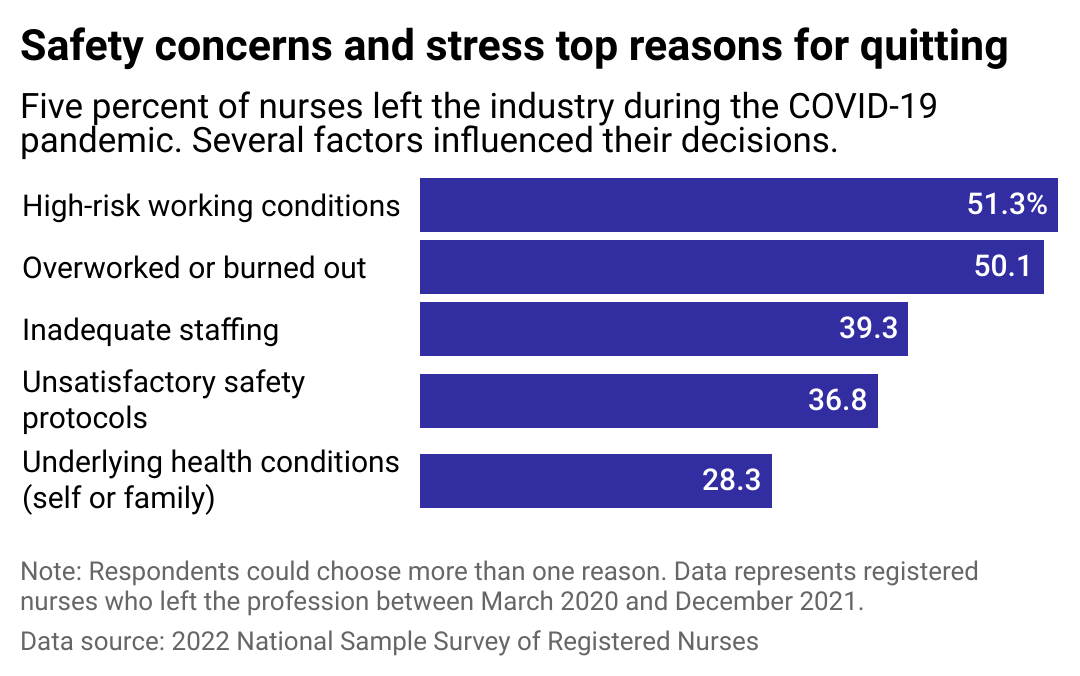

During the COVID-19 pandemic, high patient volume, a shrinking workforce, and new isolation policies that led to understaffing only exacerbated these challenging dynamics—and they show no sign of letting up. Now, four years after the onset of COVID-19, the 2023 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report indicates burnout levels are still on the rise.

An online job bank for health practitioners, Vivian Health, examined data from the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Labor, and other sources to explore the myriad factors leading nurses and other health care professionals to make career shifts to avoid burnout.

Over a third of health care professionals say their level of burnout is worse this year than in 2023, according to the 2024 Vivian Healthcare Workforce Report.

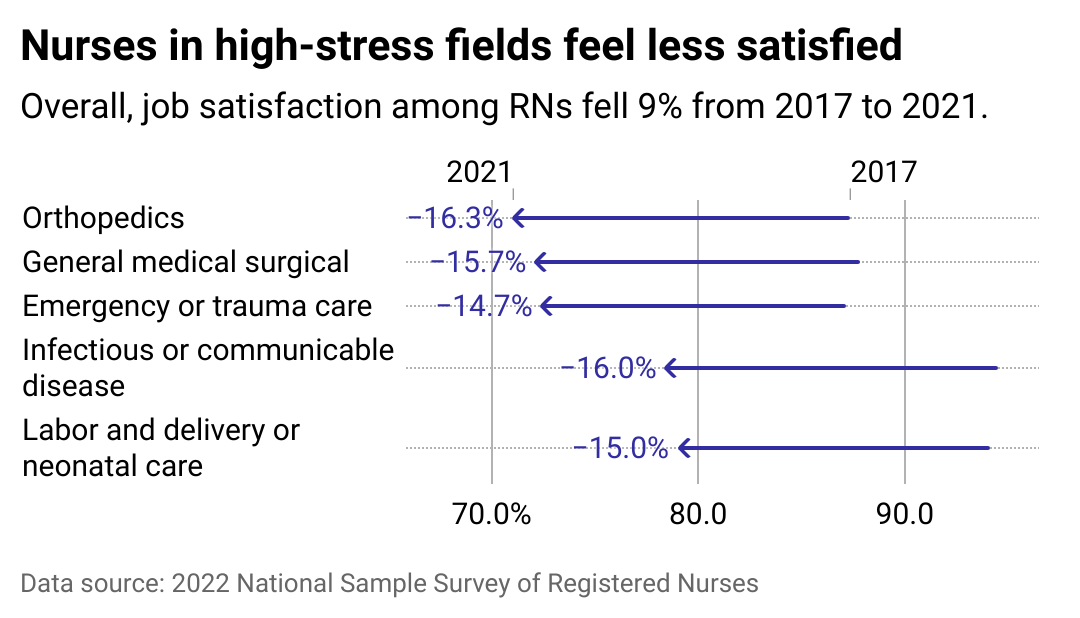

A 2022 National Center for Health Workforce Analysis job satisfaction survey found over half of nurses have considered leaving their profession, citing burnout and stressful work environments as two leading reasons. The picture is more dire in critical care: In 2021, an American Association of Critical-Care Nurses survey found that 67% of nurses planned to leave their current position in the next three years.

Amid ongoing struggles, health care workers are making career shifts, opting for less stressful work environments like outpatient settings instead of hospitals and critical care.

![]()

Vivian Health

Long hours drain on mental health

Leading up to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout among the health care workforce had reached “crisis levels,” with about half of nurses and physicians reporting burnout symptoms, according to the National Academy of Medicine.

While health care workers have long dealt with challenging working conditions, COVID-19 exacerbated workplace stress. In surveying health care workers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 1 in 2 people felt burned out in 2022, compared to 1 in 3 people who reported burnout levels in 2018. Rising levels of workplace harassment and decreased trust in management were also concurrently reported.

Staff shortages, isolation policies, and the politicization of COVID-19 all contributed to burnout among health care workers during the pandemic. Health care workers responsible for implementing mask policies and other COVID-19 restrictions became the enforcers, prompting strained patient relationships.

Frontline workers responded to these challenges in several ways. In 2023, 75,000 health care workers went on strike against Kaiser Permanente over wages and staffing shortages, which became the largest health care worker strike in U.S. history. Some health care professionals, discouraged by staffing shortages, low pay, and the rising threat of on-the-job violence, opted to leave the workplace altogether. Others sought opportunities in outpatient settings and clinics, where flexible scheduling and less stressful workdays can allow for an improved work-life balance.

Ambulatory care, in particular, is an attractive outpatient setting. With inpatient beds routinely filled in hospitals, ambulatory care that services less acute needs appeal to many health care workers. With their lower costs and shorter required stays, outpatient services like retail clinics, urgent care, and primary care clinics provide a more intimate and cost-effective experience for providers and patients alike.

Plus, the field is growing: The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that more than half of the 3.4 million health care jobs will be in ambulatory care services by 2028.

Vivian Health

Some fields more impacted than others

People in certain health care settings report very high levels of stress, with job satisfaction declining among nurses in emergency and trauma care. Health care workers in critical care settings are also the most likely to experience on-the-job violence in the form of verbal and physical abuse, often from patients’ family members. According to a 2023 global survey of health care workers from 69 different countries, 73% reported experiences of on-the-job violence the year before.

Nursing homes are also high-stress environments. While nursing homes reported critical staff shortages, a closer look at workplace data shows the outpatient nursing sector grew by more than 5% from 2020 to 2023. This data indicates that nurses are leaving high-stress assisted living facilities in favor of lower-impact environments, such as at-home health care services.

The research examined in the 2022 surgeon general’s advisory addressing burnout suggests workers of color, including those from Black and Asian ethnic backgrounds, across the health care system are at increased risk of burning out. They are more likely to report inadequate access to protective equipment and report higher rates of testing positive for COVID-19. In Indigenous communities, workers face additional challenges, including reduced access to medical resources and frequent hospital closures. People in rural areas deal with similar issues, such as staffing shortages and hospital closures.

For early career nurses, challenges related to COVID-19 surges that drained critical staffing pools trickled down to pre-licensure programs. Unable to participate in hands-on preclinical training to limit the spread of pandemics, some studies suggest that nurses who graduated amid the coronavirus pandemic were less prepared to meet the demands of a global health crisis, resulting in higher rates of burnout.

Early career nurses whose workload increased during the COVID-19 pandemic were also more likely to report feelings of burnout and fatigue. And, they were three times more likely to self-describe as “emotionally drained,” “burned out,” or “at the end of their rope” than their more tenured colleagues.

The compounded consequences of these studies are dire: In 2022, McKinsey researchers projected a gap of 200,000 to 450,000 nurses in the United States by 2025.

Dragana Gordic // Shutterstock

Health care workers prioritize work-life balance

Burnout among health care workers has a profound impact on the entire health care system. It results in poor outcomes for patient care, including decreased time spent between patients and providers, increased medical errors and hospital-acquired infections, and more staffing shortages.

Workplace burnout also increases the risk for heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, fertility issues, and other mental and emotional disruptions. Moral distress and moral injury, or the profound guilt or shame when making challenging health care decisions, are also associated with burnout.

Addressing burnout in the U.S. health care system will require dramatic changes. Cultural shifts—such as the CDC’s recommendation for more supportive management that includes worker input—could go a long way in relieving stress and retaining health care staff. In 2022, the U.S. surgeon general issued an advisory calling for the protection of the health and safety of all health care workers, sending a strong signal about reducing career fatigue.

On a systemic level, creating opportunities for workers to take paid leave or short reset breaks is also recommended. Employers are encouraged to eliminate punitive policies or attitudes toward seeking mental health and substance use treatment that might deter health care workers from accessing these resources.

Federal funding for public health and policy investment are also practical steps to curb staff shortages in this sector while ensuring that health care workers, who put so much of their lives into helping others, can thrive.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass and Kristen Wegrzyn. Copy editing by Sofía Jarrín.

This story originally appeared on Vivian Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.