Does the American education system really lag behind other countries?

Published 1:15 pm Thursday, August 1, 2024

Does the American education system really lag behind other countries?

Headlines often paint a grim picture of the American education system compared to peer nations. However, broad strokes about underperforming American students don’t capture key details of the story. The U.S. education system and student achievement are varied and complex.

To be sure, American education has room for improvement. Standardized reading and math exam scores remained relatively unchanged since the 1970s before falling slightly between 2020 and 2022. Although COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdowns are in the rearview mirror, their lasting impact is apparent in high student disengagement rates and chronic absenteeism. In 2023, the average state-level rate of students missing at least 10% of classes was 26%, a significant increase from 16% in 2019, according to data from FutureEd.

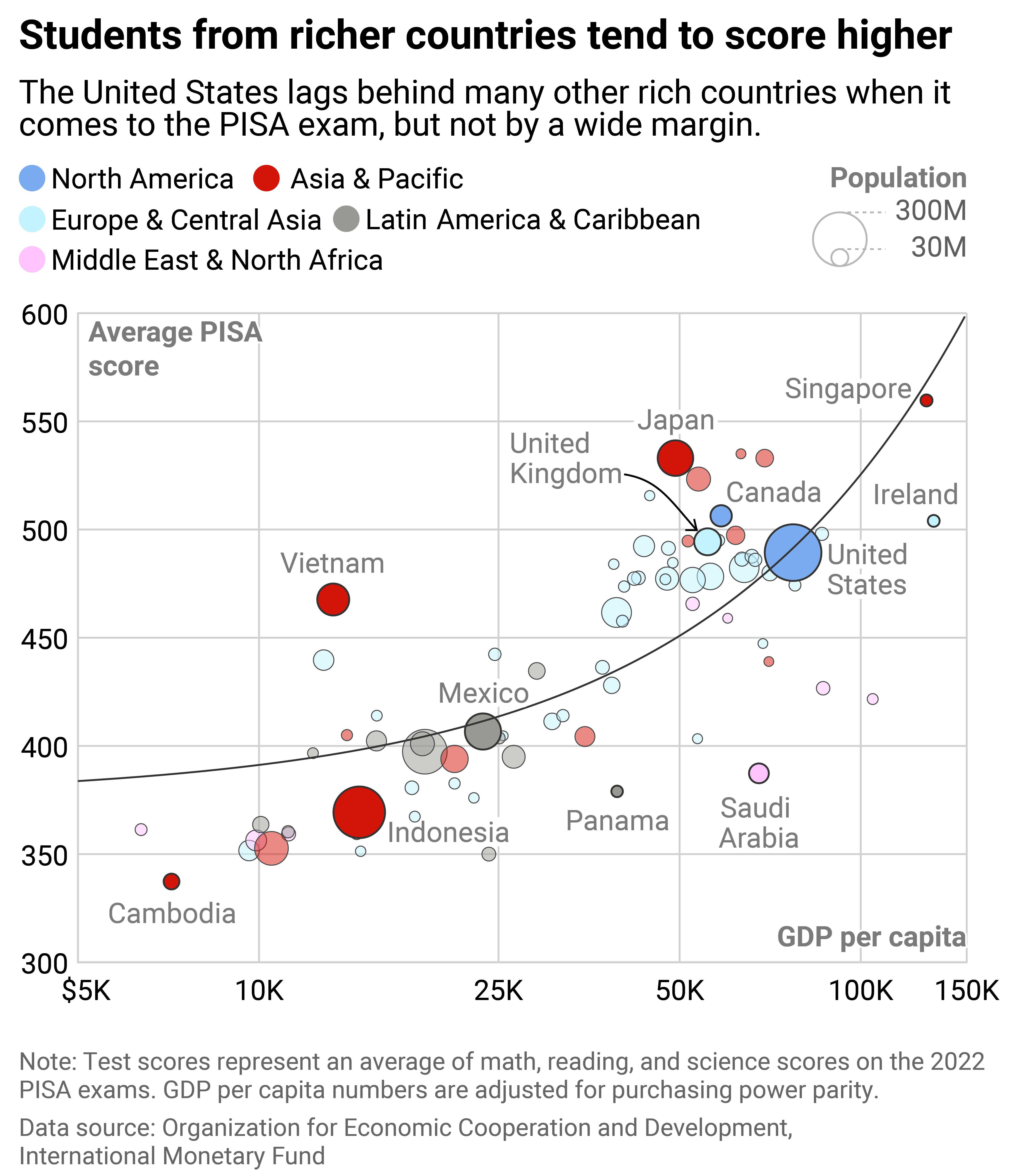

Globally, the primary tool for measuring the effectiveness of education systems is the Programme for International Student Assessment test. Administered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development every three years, PISA measures a 15-year-old’s mathematics, science, and reading proficiency.

Numerade analyzed data from the OECD to see how the U.S. compares with the rest of the world in its academic performance.

On the most recent PISA test in 2022, the U.S. ranked 20th out of 81 countries and territories, which comprise 90% of the world’s economies. Rankings were based on average scores across all three main PISA subjects.

Because America is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, there’s an expectation that it should rank higher among countries like Japan, South Korea, and Finland, ranked third, fifth, and 12th, respectively, known for their outstanding education systems. However, a closer look at the data reveals a more nuanced story. While the U.S. does lag behind other developed nations, and some studies show a correlation between economic growth and academic achievement, the exact relationship between economic resources and test scores is complex. And that’s especially true in a country as expansive and diverse as America.

For one thing, the U.S. had the largest population out of any country the OECD tracked in 2022. It also has a decentralized education system, where what students learn varies tremendously depending on their state or even their county. Many other countries have only a single national curriculum.

As one of the most diverse OECD nations, America’s cultural and ethnic makeup also plays a role. American educators must adapt to students from a wide range of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Critics of the PISA in the U.S. also note that the higher percentage of disadvantaged students compared to other OECD countries impacts the nation’s overall test performance.

Factors such as these make it hard to draw lessons about the country’s education system as a whole.

![]()

Numerade

Wealth and education

Plotting countries’ average scores on the PISA exam against gross domestic product per capita tells a compelling story. The latter measure, which represents the total economic output of a country divided by its population, is often used as a measure of economic prosperity. GDP is, in theory, indicative of citizens’ economic well-being and the nation’s resources to spend on education.

Wealthier nations tend to have better educational outcomes, perhaps because they invest more in their school systems. The U.S. has an average PISA test score in line with nations that have a similar per capita GDP. America’s scores are just below peer countries such as Denmark and the United Kingdom, but are slightly above those of Germany and France.

However, using GDP per capita as a guide for student performance has its limitations. Take Ireland, for example, which ranked ninth on the PISA. Its GDP figures are inflated due to its status as a tax haven for multinational corporations, making its economic output seem disproportionately high compared to actual living standards.

Similarly, oil-rich Gulf nations like Saudi Arabia may have high GDP per capita numbers that don’t accurately reflect the median household’s resources or living standards. Economists blame this on the “resource curse,” where countries that rely heavily on exporting commodities tend to have worse public services than countries with similar income levels but more balanced economies.

Students from Saudi Arabia and Ireland score below expectations based on GDP per capita. This discrepancy is less because their education systems are faring exceptionally poorly and more because the typical resident is not doing as well as the economic measure suggests. In other words, a country’s aggregate economic numbers can sometimes be an unreliable measure of its overall development.

Nikol Fific // Shutterstock

Lessons from high-performing nations

Several countries that ranked high on the PISA are worth studying. Despite coming from one of the world’s poorest countries, Vietnamese students perform well on the PISA exam. A 2021 study by researchers at the World Bank and the University of Minnesota found that even after controlling for many observable factors, such as parents’ education, teachers’ qualifications, and access to books and computers, Vietnam still outperformed many other developing countries. Unable to find a definitive answer to why the Southeast Asian country’s students score so highly, they speculated that Vietnam’s education system is more efficient.

Singapore offers another interesting case study. Singaporean ranked first on the 2022 test. Singapore is extremely rich as a global financial center; few nations match its wealth. According to the IMF, after adjusting for purchasing power, Singapore had a GDP per capita of $129,000 in 2022, compared to the United States’ $77,000. But, the country also has a notoriously rigorous education system, and it is common for parents to hire private tutors for their children. The country is also a city-state, making its government highly centralized.

Estonia, another high-performing country, provides clues about how to improve education systems. The Baltic country is not exceptionally wealthy, but it beat out every other non-Asian country on the PISA exam. It has a highly egalitarian education system, where all children start kindergarten at age 3. School lunches and transportation are free for all students. Estonian teachers have high amounts of autonomy, allowing them to tailor their teaching methods to individual students’ needs. All parents enjoy one-and-a-half years of parental leave, which means they can spend more time with their children when they are still young—a critical period for brain development. And the country, which bills itself as a “digital republic,” has been keen on embracing technology in education, gathering data about how students learn.

It’s worth noting that the COVID-19 pandemic caused a massive disruption in schooling worldwide. Average scores on the PISA exam fell across the world. In OECD countries, average math scores dropped by around 15 points compared with 2018. That works out to be roughly three-quarters of a school year. Reading scores fell by 10 points, while science scores did not change. Although not all of the drop can be attributed to the pandemic, this fall in test scores was the largest on record.

Countries that want to improve their education systems may have to find clever solutions. Investing more in education, experimenting with new approaches to schooling, valuing teachers, and giving parents more flexibility, as the Estonian government has done, could make a meaningful difference.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Numerade and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.