Left powerless: Non-English–speaking parents denied vital translation services

Published 3:30 pm Tuesday, November 5, 2024

Left powerless: Non-English–speaking parents denied vital translation services

For months, Wendy Rodas felt disempowered and silenced whenever she tried to reach out to her daughter’s Missouri elementary school.

The El Salvadorian mother of three, who primarily speaks Spanish, struggled to communicate with teachers, administrators, and district leaders. She made repeated requests for the interpretation services that she—and all public school parents who don’t speak English fluently—are legally entitled to.

In most of her exchanges with the school, Rodas said she wasn’t even offered access to a phone translation service. If she ever needed to inform them of something like an absence or a kid running late, she had to rely on her older son to translate, The 74 reports.

This reached a fever pitch in the fall of 2022, when Rodas’s daughter, then a 5th grader in South Kansas City, told her mom that two kids at school “were touching her inappropriately in her private parts.” When Rodas contacted the school to report this, they initially provided her with a phone interpreter, she said, but as the situation escalated over the next few months, communication dwindled.

At a meeting with district leaders to discuss the assault allegation and the attacks on her daughter that Rodas said took place afterward, the mom said she was denied any school-provided interpretation services.

“I felt powerless, not being able to say what I wanted to say, how I wanted to say it, in the manner and moment that I wanted to say it,” Rodas said in a translated interview with The 74. “And it also made me feel bad. There were a lot of times that I felt … if I was not like them—because I can’t speak the language—that I didn’t belong there. I felt ignored.”

Rodas’s experiences are not unique, according to interviews with over a dozen parents, advocates, lawyers, and academic experts, along with a review of national data. Parents and families who speak a language other than English are frequently denied access to communication from their child’s school in their primary language, often turning to Google translate, their own kid, or a bilingual staff member who isn’t a trained interpreter for issues as simple as their child being absent for a day or as complex and intimidating as a special education meeting or a school disciplinary hearing.

All of this can lead to a breakdown in trust between families and schools and harmful consequences for students—and it’s happening all the time in districts across the country, advocates say.

“It’s such a prevalent issue that everybody knows about it,” said Nancy Leon, director of the D.C.-based immigration advocacy organization MLOV—Many Languages, One Voice. “It’s unspoken. It’s expected. So sometimes it’s something parents don’t even bring up to us because it just happens so frequently.”

It’s challenging to pin down just how widespread the problem is because a number of parents don’t know that they’re legally entitled to these services, advocates say, and those who do know their rights are often afraid to report violations or unaware of how to tackle that process. Others still may feel embarrassed to request the services, viewing their status as shameful or a burden.

Another Missouri mom told The 74 that she marked on enrollment papers that she needed an interpreter, but then when her son got hurt at school one day, was put on the phone with someone whose Spanish was so poor that she just told them to speak to her in English.

One measure of the extent of the problem is the number of times children are called on to interpret for their parents at school. Tricia McGhee, director of communications at Midwest-based Revolución Educativa, said they put that question to kids when the advocacy group is doing programming with Spanish-speaking families.

When they ask, “‘Have you ever been [an] interpreter for your mom?’ They all raise their hand,” she said. “Every last one of them.'”

![]()

The 74

Countless Examples

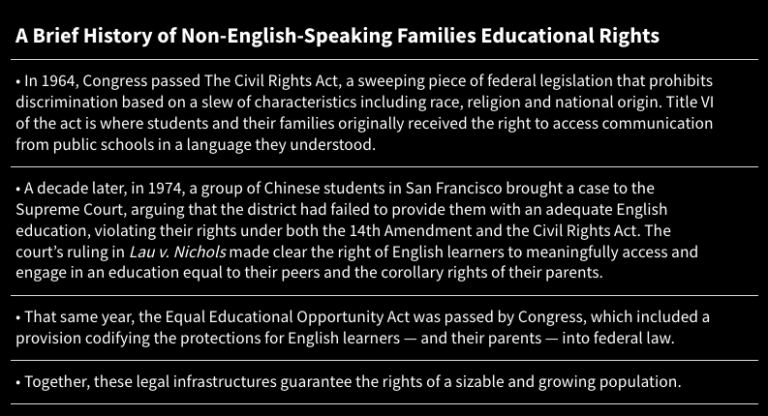

This year marks the 60th anniversary of The Civil Rights Act, which granted families the legal right to interpretation and translation services from public K-12 schools under Title VI.

Unlike for legal and medical interpreters, there is no national certification for education interpreters, though one is in the works, according to Ana Soler, chairperson at the National Association of Educational Translators and Interpreters of Spoken Languages. This leaves those in education largely unregulated, which means that even when parents do get an interpreter, they might not have sufficient training or expertise. And, they’re frequently accessed through a phone service, described by some as “check-off-the-box” language access.

In 2023, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights received about 3,500 complaint allegations raising Title VI issues. Of those, only 54 were related to communication with parents who don’t speak English fluently. They ranged from a child in Colorado denied access to free and reduced-price lunch—and later fined—because of miscommunication to a Rhode Island district’s widespread use of untrained interpreters and translators. The previous year, there were even fewer communication-based complaints filed: just 34.

But experts, advocates, and parents assert that these numbers represent a sliver of the problem.

“We have seen countless examples of schools not providing interpretation at meetings, of parents going to schools and being told that there isn’t anybody there who speaks their language, and so they should come back at another time,” said Rita Rodriguez-Engberg, director of the Immigrant Students’ Rights Project at Advocates for Children of New York.

“Whenever we hear about an example in a school, we know that there are probably dozens of parents who have gone through the same thing at that school because we’re lucky enough to get the one parent to tell us about it,” she added.

The Legal Standard: ‘A Very Tricky Balance’

In 2021, just over 10% of K-12 students nationally were English learners. In some states the percentage of children whose parents are not fluent in English can be even higher, ranging from 33% in California to nearly none in Montana, according to Education Week research. And in 2021, about one-fifth of school-age children spoke a language other than English at home and about 4% also lived in “limited-English-speaking households.”

The 2023 Family Needs Assessment, which surveyed 980 families, the vast majority of whom identified as Latino with kids who are English learners, reported almost 60% of parents being at least somewhat concerned about the lack of access to translation or interpretation services at school.

In January 2015, the departments of Justice and Education released joint guidance outlining what these services should look like: Schools must communicate with parents in a language they understand and are prohibited from asking “the child, other students, or untrained school staff to translate or interpret.”

Interpreters and translators must have knowledge of specialized terms in both languages and must be trained in the role, including the ethics of interpreting and translating. The document clearly establishes, “it is not sufficient for the staff merely to be bilingual.”

It’s important that families understand “this is not a favor they’re doing for you,” said Soler. “They need to provide you with language access that is quality language access—not just anybody that speaks a little bit of one language so that they can fulfill their requirements.”

Despite their legal heft, these provisions are often misunderstood or flagrantly violated, experts and parents told The 74. And some argue the guidance doesn’t go far enough.

“Quite frankly, the verbiage is left up to interpretation,” said Revolución Educativa’s McGhee. “So if I were passing laws, I would be much more specific about the requirements.”

The standard is not completely clear when it comes to school staff who are multilingual serving as interpreters, said Paige Duggins-Clay, chief legal analyst at the Texas-based Intercultural Development Research Association, so “it’s a very tricky balance.”

And when these rights are not sufficiently met—and parents are hobbled in their efforts to advocate for their children—the consequences can be deeply harmful to both students and families.

“Having a really engaged caregiver is critically important to the success of any young person,” said Duggins-Clay, “but especially a young person who might be new to the school community or might be learning to speak English and integrating into the broader school community.”

Often schools and districts claim interpretation and translation services are expensive and budgets are tight or they don’t have access to certain languages locally, said Alejandra Vázquez Baur, a fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank based in New York City.

But, she said, these are all barriers that can be overcome.

Schools have also increasingly struggled to recruit and retain bilingual educators, though Vázquez Baur, who is bilingual and a former teacher, again emphasized that merely speaking another language is not enough.

When she taught in Florida’s Miami-Dade County between 2017-19, she said she was frequently relied on to translate and interpret for families.

At the time, Vázquez Baur said, “I did not realize that them calling me down for parent-teacher conferences for other teachers and calling parents for all the different things was against their right.”

Superintendents and school leaders across the country want to fulfill their legal obligation and communicate effectively with their parents, but are often thwarted by an “implementation gap,” according to John Malloy, the assistant executive director for the Learning Network at The School Superintendents Association and a former superintendent in California.

The challenge comes from both pipeline and funding issues, he said: “There’s a lack of professionals to fulfill that [legal] obligation, and then there’s a lack of dollars to pay those professionals.”

The problem is endemic, he added, noting, “I think you’d be hard pressed to find a district—even in the face of our legal obligations—who isn’t struggling [with this].”

In order to combat it, Malloy said, schools will require increased state and federal funding.

“Too often in my experience—whether we’re talking special education, whether we’re talking Title IX, whether we’re talking this important and legal requirement related to access—we’re stretching dollars in multiple ways,” the former superintendent of 15 years said. “And at the end of the day, we are expected to do something that we might not actually have the resources to provide no matter how hard we try.”

Until then, school leaders will continue to rely on other strategies, such as family members or untrained bilingual staff, according to Malloy.

The school principal of a rural, low-income district in Eastern North Carolina told The 74 that he was able to hire a front office secretary who is both bilingual and a trained interpreter.

“But most people aren’t that lucky,” said Patrick Greene, who is in his 12th year as principal in Greene County Schools, a district of 2,700 students.

Finding a trained, bilingual staff member was important to him because his student population is now about a third Latino, with only one designated interpreter for the entire district. Greene said he was forced to schedule “more official” meetings, such as disciplinary hearings, around that lone staffer’s schedule.

“He stays very busy,” he said.

All of the Great Details Are Just Gone

Alejandra, who moved from Mexico to Missouri two decades ago, gave birth to her son Danny three years later. Described by his mother as a bright, hyperactive kid, Danny was in third grade when he was badly injured on the monkey bars at school.

Alejandra requested only her first name and her son’s nickname be used because she feared retaliation from her son’s school district.

After Danny walked himself to the nurse’s office that day—and after the initial interpreter spoke such poor Spanish that Alejandra told her to switch to English—it was the little boy himself who had to explain the fraught situation to his mom.

“It was very frustrating,” she added, “because they ended up using my child as the interpreter.”

This experience was not new, nor has it changed in the years since. Alejandra said that in general, when her kids were in elementary school, the school would make an interpreter available, but only if she scheduled an appointment ahead of time.

“In middle school, there are no interpreters. You have to bring your own person that will help you. And for high school? Definitely not.”

In general, even when interpretation has been provided, she described it as subpar and largely unhelpful, marked by translators who cross boundaries, interjecting their views into conversations in ways that she said were inappropriate and ultimately hurt her son.

“Oftentimes, what I’ve experienced is that when they’re part of the district, they insert themselves in the situation,” she said. “Their own bias comes in, they give their own opinions, and then they get in the way of the proper communication that should just be a bridge between one party and the other.”

It’s often in the face of these deficiencies that the student gets called on to translate. Not only is this a violation of the law, but also makes families feel disconnected from their schools and leads to an adultification of children, said Daysi Ximena Diaz-Strong, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Work.

“It creates a kind of interesting family dynamic of parents wanting to support their kids, but having these sort of structural constraints, which then forces the kids to take on more responsibility within the home.”

She said as someone who grew up as an immigrant and took on these responsibilities herself, “It stays with you all the way through adulthood. You just know that you … are responsible for your family’s well-being and that you must take on that burden at any expense—including your own.”

Sometimes, students are even pulled to be translators for their peers, according to Hannah Liu, a policy analyst at the The Center for Law and Social Policy in D.C.

It’s not just an individual school issue, she said, “it’s a very widespread issue. And I think that’s something that’s been normalized in the immigrant child experience … We need to denormalize and say, ‘OK, actually, we are not supporting our kids enough.'”

McGhee, of Revolución Educativa, said unless translation is requested in advance, it’s typically not available and even when established advocacy groups like hers make the ask, often it’s still not provided. What happens then, she said, is administrators will pull in someone like a bilingual secretary to fill the gap.

“If the student is a middle schooler or above, they are doing all their own interpretation,” she said.

McGhee said she once sat in on an emotionally charged disciplinary hearing for an English learner facing expulsion. His mom didn’t speak English, so the school ultimately brought in a young, bilingual staff member who worked in the front office but had no training in interpretation.

As the meeting intensified, the staff member grew increasingly emotional and began to cry. McGhee said she turned to her and offered to take over.

McGhee said she’s also witnessed meetings where bilingual staff members are burned out and frustrated after being repeatedly asked to do this work and therefore do the bare minimum.

Christy Moreno, community advocacy and impact officer at Revolución Educativa and a trained language access provider, emphasized the harm that is done when this happens. Moreno interpreted the parent interviews for this article.

“Oftentimes what I see and what I experience and what I hear about is meetings where when the information is translated into their language of preference, it’s summarized,” she said. “So all of the great detail, all of the very important things that need to be taken into consideration when families are making decisions about the educational experience of their children, are just gone. And so they’re disenfranchised. Someone else is making decisions for them without their true input and ultimately that impacts their student, the child.”

She’s even seen cases in which legal documents, such as Individualized Education Programs, are translated using Google: “I’ve seen it many times, literally printed on the IEP where the top corner says ‘Translated by Google Translate.'”

“It’s not really a system that’s working,” said Rodriguez-Engberg, from Advocates for Children. “The problem is that there are resources and there is guidance and there’s definitely a little bit of oversight, it’s just that I’m not sure the schools are actually being held accountable.”

Unlike federal laws that protect students with disabilities, she added, the enforcement mechanisms just aren’t very robust.

“I Want People to Know My Story”

Wendy Rodas said her daughter was hospitalized in December 2022 as a result of being victimized in her Missouri school, and that her son was forced to interpret a challenging conversation between his mother and the school principal about his younger sister’s traumatizing experiences.

Eventually, frustrated by the school’s lack of response, Rodas involved Child Protective Services and requested a meeting with the principal, superintendent, and director of student services. She also requested an interpreter be present.

At this point, a skeptical Rodas also elicited outside help from Revolución Educativa. On the morning of the meeting, the interpreter she had requested from the school wasn’t there, she said. A staff member in the session tried unsuccessfully to access one on the phone. Finally, the Revolución Educativa advocate, a trained interpreter, stepped in.

For the first time, Rodas said, “I felt like I was finally able to say everything I wanted to say.”

Rodas said she never saw the outcome of the investigation into what happened to her daughter. But in the year and a half since, the young girl has been healing through therapy and has transferred to another public school in the district, one that consistently offers translation through a phone interpreter, her mother said. This is better than nothing, but still feeling disconnected, Rodas continues to rely on outside services and volunteers.

Rodas is hoping for change—ideally a bilingual staffer is assigned at each school to facilitate communication between educators and families. And while reliving her daughter’s story is painful, she said she shares it to encourage other non-English-speaking parents to fight and advocate for their kids.

“I want people to know my story so that they can know that if they have the courage … they can make change. I want people to have that courage so that they can speak up, so that they can go and find answers and say what they want to say. And I want them to know that it is possible to get effective communication—we just need to push and ask for it.”

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.