Inside the fight against the counterfeit goods market, and how you can purchase wisely

Published 7:30 pm Thursday, November 21, 2024

Inside the fight against the counterfeit goods market, and how you can purchase wisely

Life-sized cardboard cutouts, lightsaber chopsticks (that actually light up!), bacon-themed bandages—these days, anything the mind can dream up can be sold and purchased online.

According to the Census quarterly retail e-commerce sales report, e-commerce accounted for roughly 16% of total retail sales in the U.S. during the second quarter of 2024. It marked a 6.6% increase from the same period the year prior. In 2022, digital commerce reached more than $1 trillion in sales for the first time, per analytics company Comscore.

While e-commerce has been a boon for big and small businesses alike, allowing brands to reach customers all over the world, the digital marketplace is still a Wild West of unregulated products, inaccurate marketing copy, and counterfeit items. According to a survey by Michigan State University researchers, 7 in 10 shoppers unknowingly bought counterfeit products online in 2023. The RealReal used data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection and Census records to highlight the proliferation of counterfeit goods in e-commerce—and what consumers can do to protect themselves.

A 2019 Wall Street Journal investigation called the e-commerce giant Amazon “a flea market” where vendors sold goods that falsely claimed to be certified or approved by agencies, even if those goods did not meet compliance standards. The paper found high lead levels in baby products, motorcycle helmets falsely claiming to be approved by the Department of Transportation, and unregistered pesticides.

Of course, babies chew on baby toys, motorcycle helmets ought to protect their wearers in a fender bender, and pesticides need to be safe for humans and the local ecosystem, but online marketplaces that don’t authenticate the marketing claims of goods make buying online safely bewildering for consumers.

![]()

The RealReal

Counterfeit seizures on the rise

There are many reasons why counterfeit items slip through the cracks. Big platforms like Amazon sell a diverse range of goods from vitamins to clothing to cleaning products all over the world, with each country and municipality having different regulations for different categories of products. As a result, the process to vet these products has to be equally as detailed.

“They monetize every single transaction on their platform, either in terms of a cut of the monetization or in terms of the data,” Ramesh Srinivasan, a professor at the department of information studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Stacker. “If you’re monetizing counterfeit sales, you then have at least a material responsibility tied to the benefits that you’re getting from such sales.”

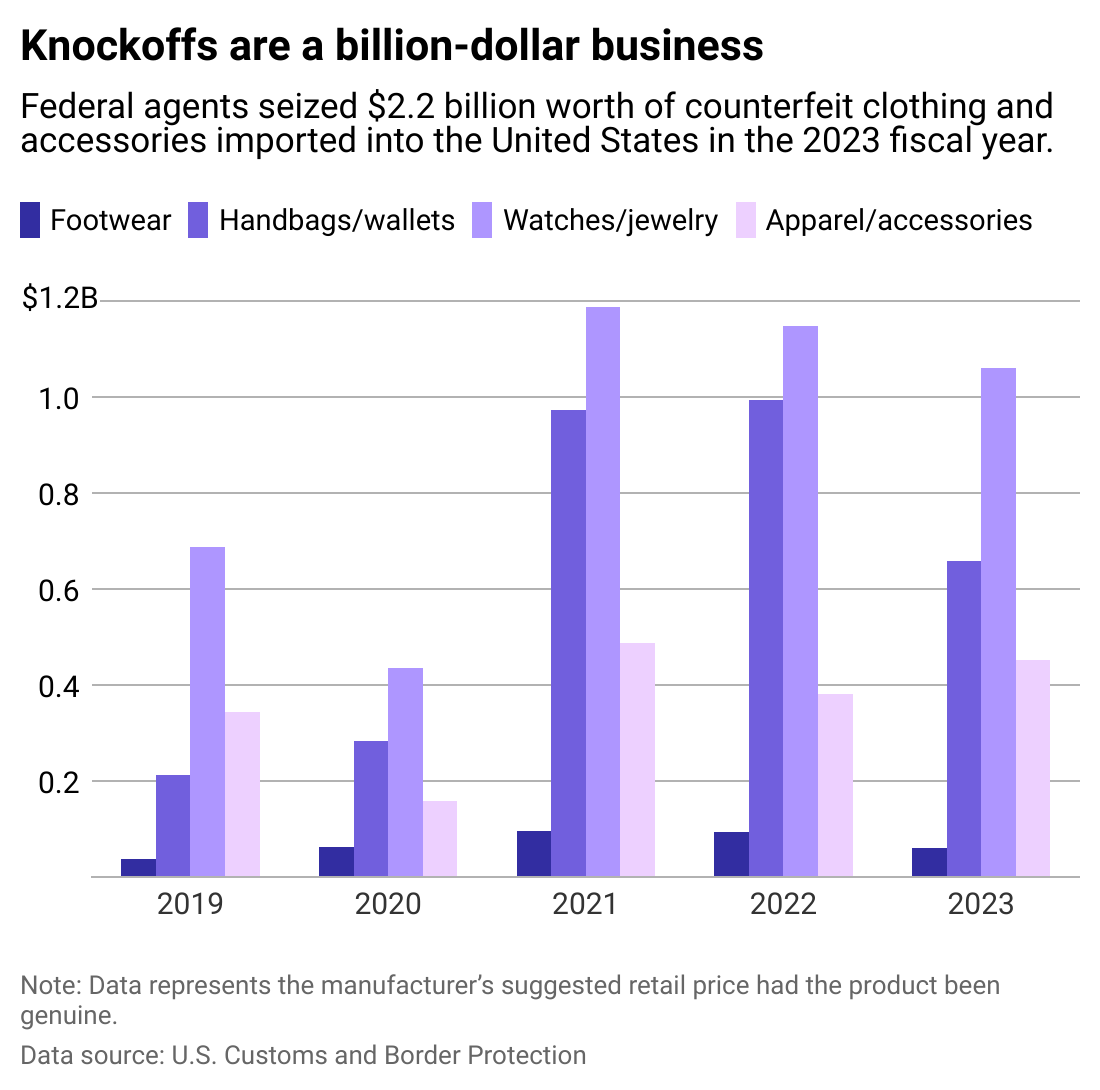

The Customs and Border Protection agency, which is in part responsible for enforcing intellectual property rights and upholding trade laws, seized $3.33 billion worth of counterfeit goods in 2021—during the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, that number dropped to $2.76 billion, which is still a 111% increase from 2020.

Items found to be in violation of trade and intellectual property rights mostly hail from China, Hong Kong, India, and the United States, according to a 2023 Customs and Border Protection report. When ranked by value, popular counterfeit items include handbags and wallets, jewelry and watches, and apparel.

Globally, counterfeits represented up to 3.3% of world trade in 2016, according to the latest study available by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and EU Intellectual Property Office. According to their study, globalization, the increased importance of intellectual property in helping boost sales, and low levels of governance are all contributing to the rise of counterfeits. COVID-19 only exacerbated those factors, filling in the need for essential goods as supply chains were disrupted.

Ann Haritonenko // Shutterstock

What’s being done to fight counterfeits

In the 2019 Wall Street Journal story, Amazon argued it was a selling platform, not a seller, and therefore was not responsible for deceptive claims made by vendors on its site. The SHOP SAFE Act, a bipartisan-led bill reintroduced to the House of Representatives in June, may render that excuse useless.

“All these platforms, whether it’s an e-commerce platform, or whether it’s a social media platform, they basically treat themselves like they like open marketplaces, so to speak, for voices or posts or products,” Srinivasan said.

The SHOP SAFE Act, an acronym for Stopping Harmful Offers on Platforms by Screening Against Fakes in E-Commerce, could open up selling platforms like Amazon to lawsuits if consumers buy counterfeit items on their platforms. The bill lists a set of best practices for selling platforms to follow in order to monitor trademark infringement, like creating proactive screening measures and terminating accounts that have been repeatedly flagged for violating rules and selling counterfeit goods.

According to Srinivasan, legislation like this can help define what better practices are, even if they fall short of catching all counterfeit items.

“What can actually occur here is what ‘better’ is, is actually spelled out by regulatory agencies,” Srinivasan said. “Then [tech companies’] ability to adhere to those laws, we can vet.”

Apart from legislation, government agencies are also asking consumers to be more aware when algorithms fail, and they’ve provided a few recommendations on how to steer clear of counterfeits, which include checking to see that consumers are submitting secure payments on websites that begin with https://.

Brands will often publish a list of platforms they sell on—platforms not listed on the brand’s website are likely selling counterfeit items masquerading as that brand. Counterfeit goods may also have small differences in packaging from legitimate goods, such as different colors, fonts, or label sizes. Report any suspicious items to the appropriate government agency—the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center are just a handful of the web of regulators.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on The RealReal and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.