The key to constructive, personalized feedback at work? Check your language bias.

Published 4:15 pm Wednesday, December 18, 2024

The key to constructive, personalized feedback at work? Check your language bias.

With over 1 billion jobs set to be transformed by 2030, the workplace is rapidly changing. With so much on the line, feedback is essential to career growth—but some approaches to constructive criticism do more harm than good.

Prioritizing meaningful feedback can fuel a culture that puts an emphasis on progress and growth to retain the top performers, keeping them in it for the long haul to support the growth of the company. Gallup research shows that 4 out of 5 employees who reported receiving meaningful performance-related feedback from their managers were the most engaged a week later.

That’s easier said than done for managers juggling daily tasks with the responsibility of upskilling and training their teams. Add to that the pressures of nurturing and retaining top talent in an über-competitive job market, and constructive, personalized feedback tends to suffer. This, in turn, has a profound impact on leaders—especially women and people of color.

Trending

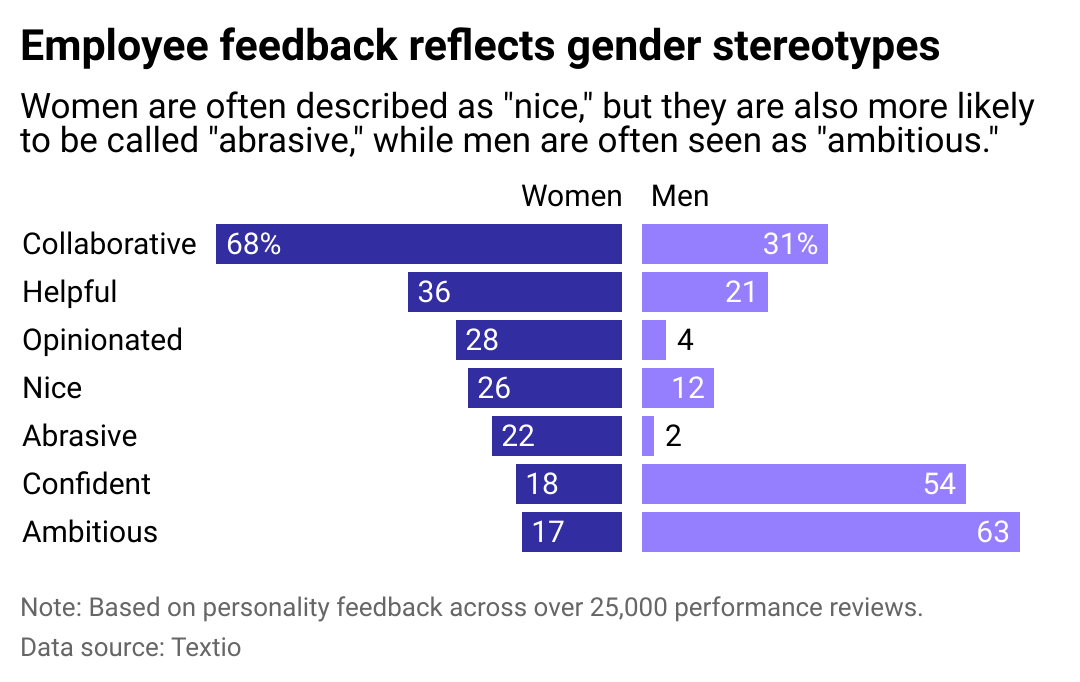

If feedback is surface-level, rushed, or riddled with biased language, it can damage an employee’s career progress. Language bias in performance reviews disproportionately impacts women and gender-diverse leaders, with 76% of high-achieving women receiving undesirable feedback compared to 2% of men, according to Textio’s 2024 report on feedback bias.

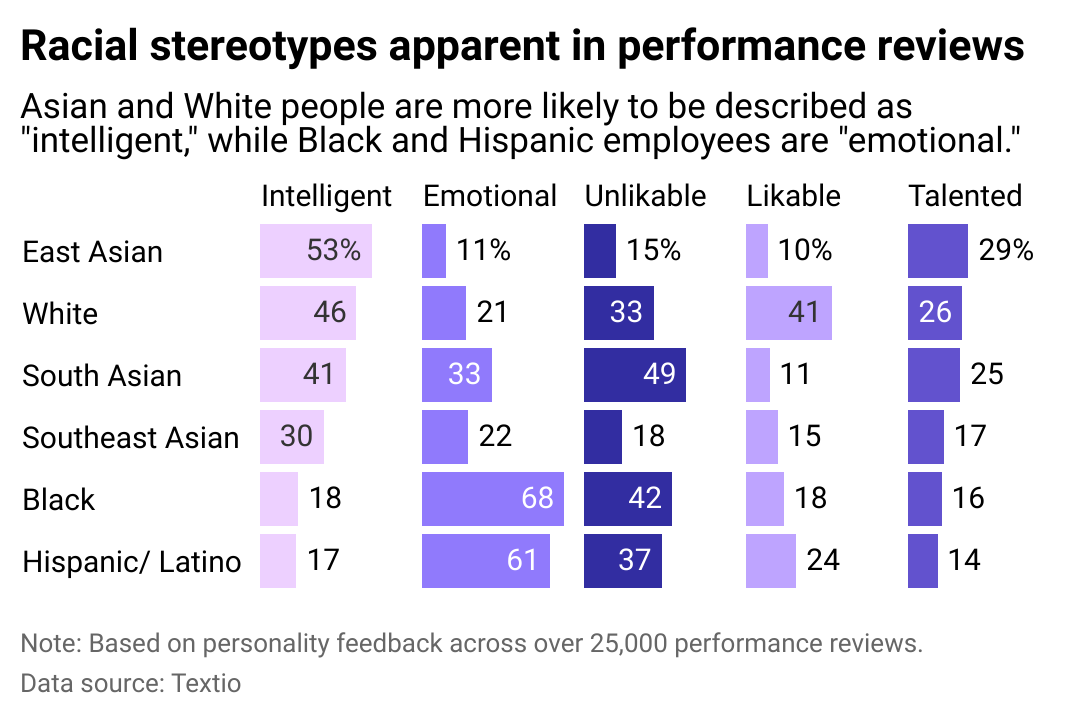

The report also found that Black and Latino/Hispanic workers were more likely to be negatively stereotyped than any other group. They report being described as “unlikeable,” “lazy” and “emotional” at work more frequently than any other groups, while Southeast Asian respondents were more likely to report being labeled as “difficult” than other groups.

When feedback isn’t linked to key performance indicators or company objectives, studies show it can hinder women’s career progression. This can lead to higher turnover rates among women and negatively impact a company’s overall performance.

Performance reviews filled with clichés and exaggerations can also fall into the trap of language bias. With terms like “emotional,” “unlikable,” and “difficult,” women are seven times more likely to be negatively stereotyped in performance feedback than men.

WorkTango examined news articles, peer-reviewed research, and recent surveys to compile tips for giving powerful, actionable feedback at work.

Textio data was collected using a binary understanding of sex and gender, which excludes important information about gender-diverse professionals. The impact of this exclusion means that this story’s coverage may lack nuance related to biased language and nonbinary individuals.

Trending

![]()

WorkTango

Gender significantly impacts internalized feedback

While men are often described as “ambitious” and “confident,” women are more frequently labeled as “collaborative.” Internalized at a higher rate by women, this perception has detrimental effects on their career progression.

Women leaders are considered kind, compassionate, and sensitive—more communal qualities—while men are associated with behaviors like assertiveness and self-reliance. The latter qualities are frequently associated with effective leadership, fueling a double standard. Women leaders may find themselves stuck trying to be both collaborative and ambitious—a balance that’s near-impossible to strike.

Researchers at the London Business School found that women are given kinder feedback compared to men, which can be equally damaging to their performance. Prioritizing kindness over honest, constructive criticism doesn’t help women improve, grow, and strengthen their skills.

WorkTango

How racial bias plays a role

Racial bias also adds an additional layer of stereotyping that can be detrimental to women’s careers. About half of white and Asian men also reported being called intelligent at work, compared to less than 1 in 5 of their Hispanic/Latino and Black colleagues.

Managers tend to use racially biased language when attributing internal characteristics to their employees, according to the report. For instance, white and Asian men are markedly more likely than other groups to be described as “brilliant” and “genius,” terms that suggest innate talent or ability.

Ascribing internal characteristics that align with racial stereotypes can diminish workers’ abilities or accomplishments, and also directly impacts how managers perceive performance. Notably, when managers review the achievements of Black and Latina women, they typically don’t refer to innate intellectual ability, the findings revealed.

Black women were also four times more likely to be described as “overachievers” than white men— a compliment on its face that’s actually “gaslighting,” according to the report. While feedback about “underachieving” suggests that a manager gives the benefit of the doubt about an employee’s potential and capacity, the word overachiever glosses over skill, talent, and hard work. The term can imply aggression and coercion among leaders, or be a euphemism for a striver always on the verge of burnout.

“In corporate America, compared to Latina, or Black and brown professionals in general, men are measured on potential whereas we have to be measured on what we are consistently delivering and we always have to outdo ourselves,” Vanessa Santos, partner and CEO of digital community #WeAllGrow Latina told Chief, a network for women in the C-suite.

What’s more, people are more likely to internalize negative feedback when it correlates with stereotypes about their identity, contributing to a fixed mindset, according to the report. In other words, feedback that reinforces negative self-perception can contribute to the belief that intelligence and talent are fixed and unable to change. When people believe they can’t grow or won’t be seen beyond stereotypes, it can sap their motivation to excel.

The impact of negative feedback in performance reviews is heightened for people of color, particularly Black women. Black people receive more than twice as much unactionable feedback as their white and Asian coworkers, and women overall were more than seven times more likely to internalize negative feedback. Personality-based, low-quality feedback not only lowers morale and pushes high-performers to quit their jobs, but also prevents them from achieving their full potential.

Jono Erasmus // Shutterstock

How to curb stereotyping during performance reviews

To combat stereotypes and mitigate biases, more businesses are turning to artificial intelligence for performance reviews. Generative AI has been shown to help managers save time gathering concrete data and provide more clear, constructive, and tactful reviews, according to SHRM.

However, AI has its limits. The Textio report found that ChatGPT used for performance reviews yielded responses that were overly generic and biased against race and gender. In other words, AI has reinforced existing stereotypes.

Providing meaningful, unbiased performance feedback can help develop top talent—especially women leaders—which is crucial to the success of a company. To ensure the feedback you provide is free from bias and yields results, focus on providing clear, specific, and actionable insights. Workplace leaders suggest leaving out vague or interpretive feedback like “inspiring” or “lacks motivation,” and instead offering feedback on the ways an employee’s actions align with organizational goals.

Starting with a healthy mix of positive reinforcement and suggestions for improvement that help cultivate personal and organizational success can help set the right tone. By being intentional about avoiding biased language and personality-based reviews, managers can start to create a more inclusive, equitable workplace.

After all, it’s the workplaces that prioritize constructive feedback, regular performance check-ins, and ongoing professional development that are leading the way in innovation and inclusion, leaving other companies behind.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on WorkTango and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.