How one controversial study shaped 20 years of menopause care

Published 4:30 pm Monday, July 21, 2025

How one controversial study shaped 20 years of menopause care

By now, many women navigating perimenopause or menopause know the headline: In 2002, a study linked hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to an increased risk of breast cancer. Overnight, women abandoned treatment. Doctors stopped prescribing it. Years later, we learned the data had been misinterpreted, but the damage was already done.

The study—one arm of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a massive trial on disease prevention in aging women—was never meant to serve as the final word on hormone replacement therapy, or even examine whether it was safe and effective for menopause symptoms like hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, or brain fog.

Recent data shows that for most women in menopause, the pros of HRT outweigh the cons, and leading experts are pushing to make this widely known. In 2025 the FDA convened an expert panel to discuss the latest evidence on HRT, with leading researchers and clinicians calling for changes rooted in the latest science.

Trending

Yet the legacy and flaws of the 2002 WHI study persist in prescribing patterns, medical education, and the options women are (or aren’t) offered to treat menopause symptoms.

Hone Health spoke with doctors who practiced before and after the WHI to unpack what the study actually showed, its flaws and how the message got distorted, and what it will take to finally move menopause care forward.

Early 1990s: Hormone Therapy Is Considered Essential

In 1991, the National Institutes of Health began recruiting for the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a $625 million, long-term, randomized controlled study to investigate ways to prevent the leading causes of death and disability in postmenopausal women.

In total, 161,808 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 were recruited for the study; 68,132 participated in one of three clinical trial arms: hormone therapy, diet modification, or calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

The hormone therapy trial was intended to last nine years to evaluate the long-term health impacts of the two most common HRT regimens at the time: conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) plus progestin (synthetic progesterone) for women with a uterus, and CEE alone for those who’d had a hysterectomy and no longer had a uterus.

“We were taught hormones were the greatest thing since sliced bread. They protected women’s hearts, brains, and bones, and therefore we wanted all menopausal women to be on hormone replacement therapy,” says Deb Matthew, M.D., board-certified integrative medicine physician and author of “This Is Not Normal: A Busy Woman’s Guide to Symptoms of Hormone Imbalance.”

July 2002: WHI Headlines Change Care Overnight

Trending

On July 9, 2002, the NIH held a press conference, announcing it was stopping the estrogen-plus-progestin arm of the trial early, citing increased rates of blood clots, stroke, heart disease, and breast cancer in women taking the combined hormone therapy.

“Everybody flushed their hormones down the toilet. Patients didn’t want to take them. Doctors stopped prescribing them. Literally overnight, it just sort of stopped,” says New York City–based OB-GYN Alyssa Dweck, M.D.

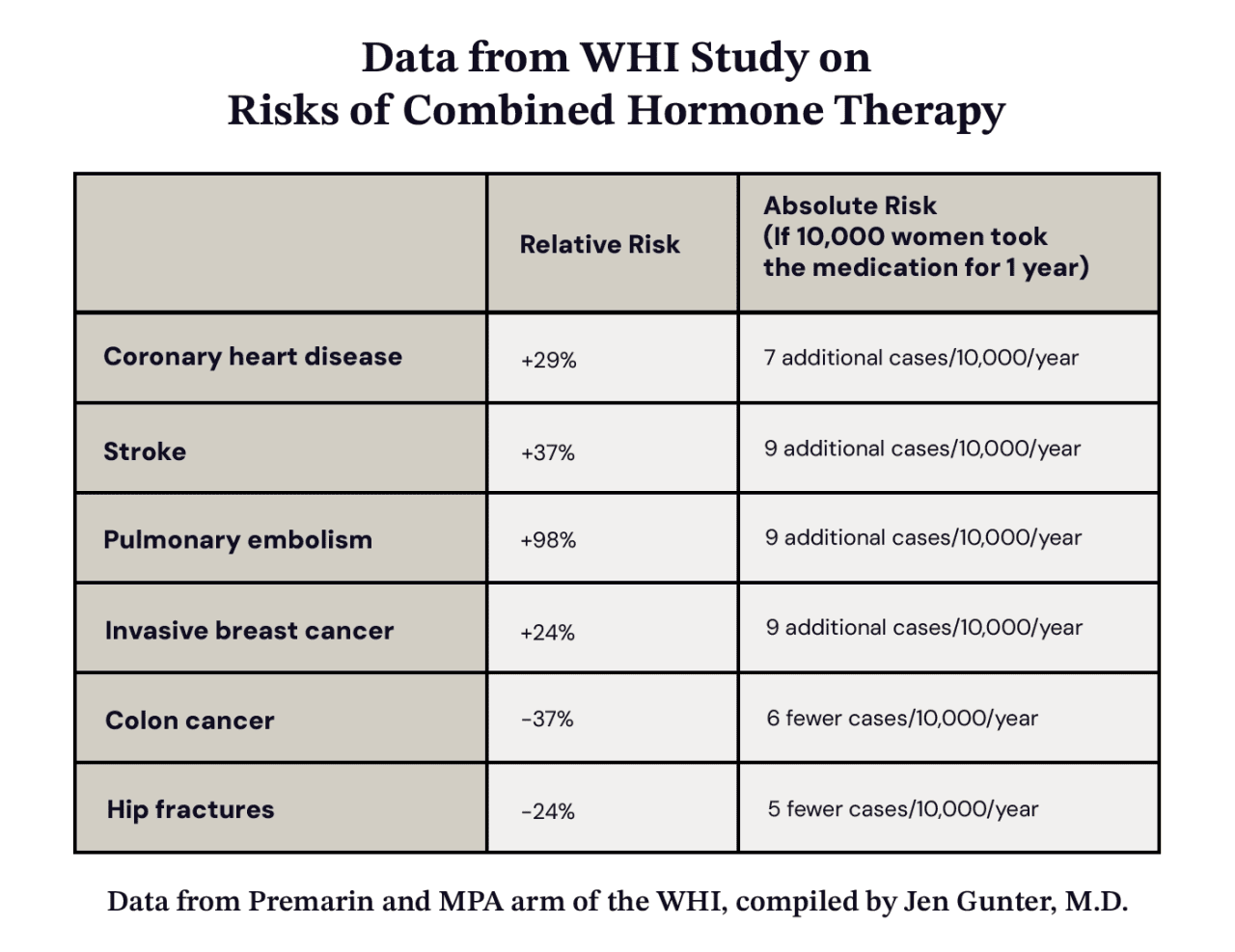

While the HRT study had also shown benefits—notably, fewer hip fractures and cases of colorectal cancer—those findings were largely drowned out by the news headlines, which rapidly spread an alarming message: Hormone therapy was dangerous.

Clinicians were blindsided.

Typically, trial data is shared with physicians in advance, giving them time to review the findings and prepare for treatment changes and patient questions. In this case, the WHI study wasn’t published in JAMA until July 17, more than a week after the press conference.

“We had no idea that the study was even released,” says Tara Scott, M.D., a board-certified OB-GYN, and Menopause Society-certified menopause practitioner.

“Phones were ringing off the hook with people frantic, not knowing how to stop their hormones,” says Robin Noble, M.D., also an OB-GYN and Menopause Society-certified provider.

Doctors were horrified that they’d been regularly prescribing a treatment that now appeared to increase the risk of breast cancer, and took women off hormones.

Hone Health

“On the first day of medical school, literally the first thing that we do is take the Hippocratic oath,” Matthew says. “And part of that oath says, ‘First, do no harm.’ So doctors would rather do nothing and allow harm to come to you than to do something that ultimately causes you to have harm.”

The 2000s: A Generation of Providers Is Trained to Avoid Hormones

Before the WHI findings were released, around 40 percent of American postmenopausal women were taking hormones to manage symptoms. Within months of the press conference, that number dropped by nearly half.

Menopause training itself, already underemphasized in medical education, also dwindled to virtually nothing. “Those who did their medical school and residency in the 2000s really had very little training on menopause and menopausal care,” Noble says.

“In residency, I saw patients who would tell me, ‘This menopause thing is kicking my ass. I can’t sleep. I have no libido. I’m gaining weight,’” says board-certified OB-GYN and integrative medicine physician Jennifer Roelands, M.D. “I was instructed that it’s just a stage in a woman’s life, and they just have to exercise more, eat less, and that’s just what happens.”

What made that retreat even more damaging: the breast cancer risk that HRT drove was small and poorly reported by the media.

The actual increase in breast cancer risk for women on the combination therapy was small—just one additional case per 1,000 women.

“They called it a 26 percent increase in the risk of breast cancer because it went from four to five,” says Matthew. “It got overblown to be a big risk, when in fact it was a teeny, tiny risk.”

That single statistic about breast cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative study, divorced from its absolute context, shaped care for decades.

Meanwhile, other benefits of HRT reported in the WHI went unreported: Women who received estrogen alone actually had a reduction in the risk for breast cancer. But that part of the WHI study was still ongoing, and by the time it ended in 2004, distrust of HRT had already calcified.

2010s: The Hidden Toll of HRT Avoidance Emerges

As it turns out, not taking HRT had significant effects on many women’s health.

A study published in 2013 estimated that between 2002 and 2012, as many as 91,000 postmenopausal women in the U.S. died prematurely from conditions that HRT might have helped prevent. “[Estrogen therapy] in younger postmenopausal women is associated with a decisive reduction in all-cause mortality,” the study authors wrote.

“Women were literally better off and lived longer on the hormone replacement therapy than they were without hormone replacement therapy, even with the tiny increase in the risk for breast cancer,” says Deb Matthew, M.D. “That information never really made it out to the public and never really made it out to doctors.”

A review published in 2018 emphasized another flaw with the WHI study trials: the age of the participants. The average participant in the hormone trial was 63, more than a decade past the typical age of menopause onset, which is 51. This matters because both age and time since menopause influence hormone therapy’s risks and benefits.

The WHI study also deliberately enrolled older, asymptomatic women to maintain the integrity of its double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Including women with vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes would have unblinded the trial, as those on placebo would continue experiencing symptoms while those on hormones would likely feel relief. But studying menopause in an older population also meant studying women who were already at higher baseline risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer, regardless of hormone use.

Today: Hormone Therapy Evolves and Gains Traction

Two decades after the WHI fallout, the cultural conversation around menopause started to shift. Celebrities like Naomi Watts, Gwyneth Paltrow, Drew Barrymore, Halle Berry, Salma Hayek, and Oprah Winfrey started speaking candidly about their experiences with perimenopause and menopause.

“A lot of really influential women who are power brokers in the media, in Hollywood, and in business were just unwilling, and rightfully unwilling, to suffer with symptoms,” Dweck says.

On social media, OB-GYN influencers like Mary Claire Haver, M.D., and Jen Gunter, M.D., have built large followings by spreading information and opinions about menopause. “That really drove a lot of patients to go, ‘Huh, I don’t actually have to suffer,’” Roelands says.

In recent years, the term “menopause hormonal therapy” (MHT) has gained traction to distinguish it from other types of hormonal therapy, but also to “rebrand” HRT and shift the therapy away from any negative connotations that still linger after the WHI study.

And education is starting to spread that today’s hormone regimens rely more on transdermal estrogen and micronized progesterone, which have been found to be much safer than the hormones used in the study.

A 2022 editorial published in Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society stated: “The best available evidence indicates that the use of estrogen with micronized progesterone… does not elevate breast cancer risk to the same degree, if at all, and are safer with respect to risk of breast cancer.” Other post-WHI research from 2013 and 2022 found transdermal HRT did not increase the risk of blood clots as oral HRT does.

Gaps Between Science and Practice Remain

Still, greater visibility hasn’t necessarily translated into more women using hormones. Research published in JAMA in 2024 estimated only about 5 percent of women in 2020 were taking HRT to manage their menopause symptoms, down from 27 percent in 1999.

“Even with this newer information that’s come out with WHI data, the amount of hormone usage hasn’t really increased all that much,” Dweck says. “It is taking a while for people to get the message that for many it’s safe and very effective.”

That “people” includes physicians. There are too few physicians steeped in menopause care, Scott says. “There aren’t enough providers,” she says. “I think there are at most 4,000 certified menopause practitioners, and they’re not in every state.”

A 2022 review of 12 studies on medical menopause education found some sobering statistics.

- More than 90 percent of medical residents said they felt unprepared to deal with patients experiencing menopause.

- One in five family medicine residents received no menopause education

- Less than 7 percent feel adequately prepared to treat menopause.

- Almost half of those residents had not received menopause management training or were unfamiliar with it.

- A full 67 percent said they did not adequately understand HRT.

That lack of clinical knowledge trickles down to patients. Many women still fear breast cancer; others favor natural remedies over pharmaceutical treatments, notes Dweck.

Experts call for policy change

With rising public awareness, growing research, and a new generation of vocal advocates, momentum has been building to address menopause care. That movement reached a milestone in July 2025, when the FDA convened an expert panel to discuss hormone therapy. Leading researchers and clinicians urged regulators to finally align policy with the best available science and to move past the shadow cast by the WHI.

Multiple experts called on the FDA to remove its current black box warning on vaginal estrogen. JoAnn Pinkerton, M.D., the past president and emeritus executive director of The Menopause Society, noted that the WHI data never supported a link between vaginal estrogen and risks like breast cancer or stroke.

Other experts proposed increasing menopause education in medical training. Mary Jane Minkin, M.D., a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Yale University School of Medicine, called for renewed curriculum standards to help OB-GYNs, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants understand the nuances of hormone therapy and symptom care.

Reframing The Study That Redefined Menopause Care

Despite the fallout and its potential flaws, experts agree the WHI remains a landmark study.

“The WHI was the largest and most comprehensive clinical trial ever performed on women anywhere in the world,” says Nanette Santoro, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “It’s the standard that other trials should be measured against. It was run by experts, the processes and procedures were state-of-the-art for its time, and its results are robust and have been reinforced by the lengthy follow-up of women after they stopped the treatment.”

But, Santoro adds, the WHI study is just like any other clinical trial: “It can tell you about one treatment at one point in time on one population.”

The real lesson of the WHI study isn’t to avoid hormones or to embrace them blindly. It’s that women deserve informed, individualized menopause care that reflects evolving science, by educated practitioners.

“We need to meet people where they are,” says Noble, “and where they want to be.”

This story was produced by Hone Health and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

![]()